https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3152910/if-us-and-eu-were-divided-china-aukus-betrayal-just-dug

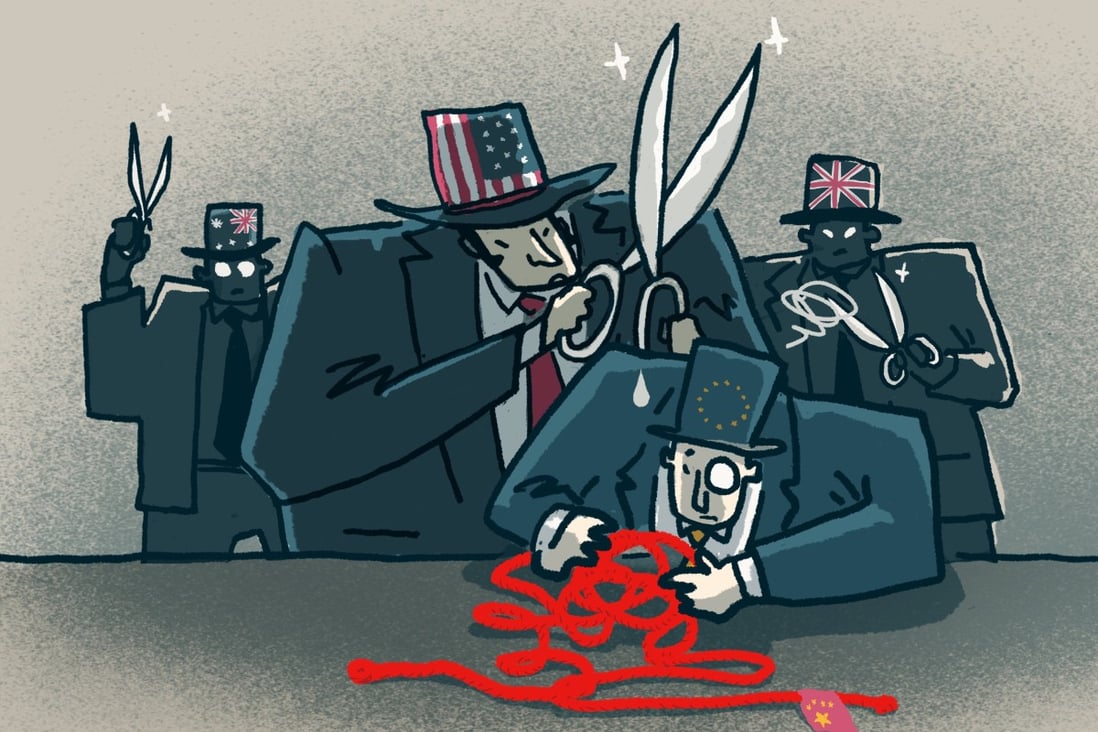

If the US and EU were divided on China, Aukus ‘betrayal’ just dug the trenches deeper

- ‘Humiliating’ news of the 3-way security deal showed the European Union the US was ready to risk old alliances to ‘get at’ China

- Despite ‘wearying’ US prodding to the contrary, and shared economic and military concerns, Brussels is determined to plough an independent furrow on China

It was not a phone call from one of his American, Australian or British counterparts that informed the EU’s top diplomat Josep Borrell about a new Anglophonic defence alliance designed to tackle China.

Rather, one of his colleagues sent him a news story outlining the details via WhatsApp, to which Borrell responded with a curt: “Caray” – a Spanish exclamation loosely translated as “damn” or “ouch” – according to a source close to the event.

The European Union and even France, which lost to Washington a US$66 billion contract to provide Australia with a fleet of nuclear submarines, were kept in the dark up until the news had been leaked.

The French described it as “a stab in the back”, while a beleaguered Borrell was sent to launch the EU’s own Indo-Pacific strategy a day later and faced a blizzard of questions on a defence pact he said he had no idea about. Commission sources described it as “humiliating”.

Perhaps more than anything, the Aukus affair and its continued fallout demonstrate the vastly different positions the EU and US occupy towards China.

In Europe, Washington is seen to view all foreign policy through a Beijing-tinted lens. Its handling of Aukus is seen as proof that it is willing to jeopardise some of its most important relationships to “get at” China.

Jim Townsend, who spent more than two decades working on European and Nato policy in the Pentagon, described the affair as “sobering” and evidence that the Biden administration had misjudged Brussels’ resolve to maintain relatively warm ties with China.

“Aukus really shows that the focus [on China] is so intense, and the disregard for the collateral damage on other parts of the world. That disregard was enough that they were going to plunge ahead, notwithstanding impact on France or other countries that are our traditional allies on problems like this,” said Townsend, who apportioned part of the blame to the fact that key figures in Biden’s EU team had yet to be confirmed.

American embassies continue to prod European capitals on a near-daily basis to toughen their positions on China, a trend that began during the Trump era and which was described as “wearying” by one European official.

In the run up to the much-vaunted launch of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council in Pittsburgh last month, there was some haggling over how much China should be alluded to in the text. In the end, it was not mentioned at all.

But the partnership did demonstrate that the allies shared wariness toward China’s growing military, political and economic muscle, even if weaving those concerns into a common strategy remains a significant challenge.

01:03

China's military rise poses ‘important challenges’ to security, Nato says

“They’re very concerned with the same things we are, the power of state-funded enterprises, the use of stolen intellectual property, the unfairness of Western firms getting involved in Chinese markets versus Chinese firms in Western markets,” said Richard Boucher, a fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute, referring to the EU.

“But there’s clearly a tendency in the United States to try and build walls against China and to see China primarily as a threat. And in Europe, I think they still see China as an opportunity,” added Boucher, former deputy secretary general of the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and US consul general in Hong Kong.

Where values are concerned ... there’s greater opportunity for the US and Europe to act in lockstep

Bonnie Glaser, Asia director with the German Marshall Fund think tank, added that while Europe is “very uneasy about confronting China”, senior German officials have told her discreetly that Europe often adopts a different stance in public but this does not suggest their interests are not aligned with the United States.

“Where values are concerned, I think there’s greater opportunity for the US and Europe to act in lockstep,” Glaser said.

Others are less sure. In an interview with the New York Times last week, French finance minister Bruno Le Maire laid out his perception of the differences in black and white terms.

“The United States wants to confront China. The European Union wants to engage China,” he said, adding that the EU must be “independent from the United States, able to defend its own interests, whether economic or strategic interests”.

This chimes with some establishment views in Berlin and Brussels, where significant political capital has been expended over the past couple of weeks to secure calls with Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Calls with outgoing German Chancellor Angela Merkel and European Council President Charles Michel are seen in some quarters as part of a diplomatic re-engagement with China, with major powers spooked by Xi’s reluctance to hold top level talks following tit-for-tat sanctions in March.

I spoke to President Xi of China today.

On EU-China relations, despite differences, dialogue remains crucial.

Agreed to hold EU-China summit and reinforce our dialogue. pic.twitter.com/YU3SXEXSyG— Charles Michel (@eucopresident) October 15, 2021

But it does not reflect the diversity of opinions throughout the bloc, where many member states hold less decisive views on China.

For this reason, it is near impossible to achieve consensus on many issues relating to Beijing, meaning it is sometimes bumped off the agenda to be replaced by matters in which they can hope to achieve progress.

One senior diplomat bemoaned France’s “whining” over the Aukus deal and its perpetual lobbying about strategic autonomy, a concept which is disliked in equal levels by some of the EU’s Nato members who want closer transatlantic ties, such as the Baltic states, and the bloc’s neutral states including Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden, which flinch at the idea of an EU expeditionary force.

“France had a big arms deal with Australia, and it all fell apart, and then we’re all roped into the aftermath. Arms deals are vicious anyway, the fact it all went sour for France and the US betrayed them, there’s not too many tears,” said an EU diplomat who did not wish to be named.

Lithuania in particular has been pushing the envelope on Beijing. A row over hosting a “Taiwanese Representative Office” has boiled over into a trade and diplomatic dispute, forcing Brussels to defend the tiny Baltic state.

Some Central and Eastern European states share Vilnius’ promise fatigue with China over unmet investment pledges, while concerns over alleged economic coercion and rising authoritarianism are widespread, even if others are less enamoured by Lithuania’s approach.

When raising the issue at EU forums, Vilnius was greeted with “a roomful of silence and some puzzlement”, according to one diplomat present, who wondered what was behind its approach.

The challenge in getting member states to focus on Beijing was laid bare in Brdo, Slovenia, earlier this month, where EU national leaders gathered to discuss China for the first time together for an entire year. But the agenda was broadened at the last minute to the more generic heading of “the EU’s place in the world”.

According to one official who was present on the sidelines at the talks, China got “about 10 minutes” of their time, while a second attendee said “[French president Emmanuel] Macron majored on the fallout of Aukus and the need for a proper EU Indo-Pacific strategy”.

Some observers view the EU-US mismatch as a natural product of geography. Lower level officials talk about China every day, while top leaders are more inclined to discuss what’s dominating the current news agenda.

As the EU deals with a constitutional crisis in Poland, military skirmishes in the Western Balkans, a potential influx of migrants from Afghanistan and the ever-looming threat of Russia – China sometimes slips between the cracks.

“Eastern Europeans still perceive a strong pressure from Russia, and also our southern flank is very unstable and that also has to absorb a lot of attention. Even if we wanted to prioritise China to the same extent as the US we couldn’t, because they are bordering Canada and Mexico, we are bordering the Sahel, the Middle East and Russia. It’s very different,” said Sven Biscop, a director at the Egmont Institute, a Brussels think tank on international relations.

US observers are hopeful that some headway can be made if the Biden administration follows through with its pledge to listen better to its allies.

03:29

US and EU must prepare for ‘long-term strategic competition with China’, says Biden

“As we’ve seen, this administration has a gap between theory and practice, strategy and operationalising that strategy,” said Daniel Fried, an Atlantic Council fellow and former US assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs.

“You have to work hard with Europe. You can’t issue a statement and think things will fall into place. You have to know what the hell you’re doing. That involves putting a team together and understanding the issues,” said Fried, who hoped that the future German coalition government might be more receptive to overtures, especially if the foreign minister position goes to the Green Party as some expect.

“The Greens are even more inclined to work with the US; the Greens have a democracy-based foreign policy,” Fried said, “especially if the US doesn’t lead with hard security issues, which are always difficult in Europe. But if it focuses on global standards, rules and regulations, those are good German buzzwords.”

“They have to listen. They can’t just jam it down their throats.”

Comments