How a Powerful Nissan Insider Tore Apart Carlos Ghosn’s Legacy

Hari Nada's score settling created chaos that haunts the carmaker to this day.

Behind every corporate coup is a mastermind. At Nissan Motor Co., that was Hari Nada, an insider known for his aggressive tactics and fondness for Marlboros, French cuff shirts and strong cologne.

The senior vice president orchestrated a campaign to arrest and dethrone then-Chairman Carlos Ghosn in late 2018 on criminal financial-misconduct allegations. The aftermath has been messy. High-profile careers were destroyed, and chaos gripped management. Nissan is losing billions of dollars, and its alliance with Renault SA and Mitsubishi Motors Corp. is at risk of unraveling. Meanwhile, Ghosn is unlikely to ever face Japanese justice after escaping to Lebanon late last year.

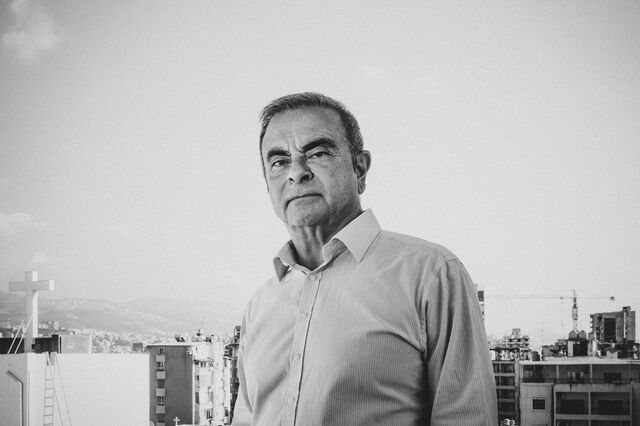

A cosmopolitan business celebrity who speaks English, French, Arabic and Portuguese, Ghosn saved Nissan from ruin in the early 2000s. Yet in this multi-act corporate drama, the other leading role belongs to Nada, 56, according to a Bloomberg News investigation based on interviews with more than a dozen people, video footage and previously undisclosed internal company documents.

The Nissan Coup: Key Players

Hari Nada

The senior vice president helped determine Ghosn’s compensation, orchestrate his arrest and provide evidence to investigators; he was involved in the internal investigation afterwards.

The senior vice president helped determine Ghosn’s compensation, orchestrate his arrest and provide evidence to investigators; he was involved in the internal investigation afterwards.

Carlos Ghosn

The former chairman of the Nissan, Renault and Mitsubishi Motors alliance was arrested in November 2018. He fled Japan in late 2019 before trial and now is in Lebanon.

José Muñoz

Ghosn’s former head of Nissan North America left shortly after the arrest and now is global COO for Hyundai Motor.

Ravinder Passi

The former general counsel was demoted in January after flagging conflicts of interest within Nissan’s investigation into Ghosn.

Hiroto Saikawa

The former CEO resigned in September 2019 after questions about his own pay. He also was involved in the planning of Ghosn’s arrest.

Makoto Uchida

The current CEO wants to put the Ghosn affair behind the company, yet Passi’s demotion happened under his watch.

Motoo Nagai

The chair of the board’s audit committee didn't act on concerns raised by Passi.

Bloomberg reported in June that Nada and a group of other senior executives, wary of Ghosn’s efforts to strengthen the carmaker’s alliance with Renault, mounted a methodical campaign to unseat the lionized leader almost a year before his arrest in Tokyo.

Now, new reporting suggests just how far Nada and his allies were willing to go to remove Ghosn from power, settle scores and make major business decisions with little oversight. Ousting Ghosn from the car-making alliance he built sent shockwaves through the corporate world. And it jolted the foundations of not just one but three well-known auto brands. The actions of Nada, who remains at Nissan as a senior adviser, haunt the automaker and its partners to this day.

Among the key discoveries:

▲ Hari Nada

Source: Nissan Motor Co.

• Nada arranged for a hack into Nissan’s computer systems and Ghosn’s corporate email account without informing key information-technology staff or the chief executive officer. That was months before he began working with prosecutors who later arrested the former chairman, according to current and former IT employees at the company.

• Former Nissan executive and Ghosn ally José Muñoz, now Hyundai Motor Co.’s global chief operating officer, also feared arrest as part of the Nada-led putsch. Summoned to Tokyo, he refused to go after tip-offs from the U.S. and Spanish ambassadors to Japan, people familiar with the matter said.

• Nissan’s top corporate attorney, Global General Counsel Ravinder Passi, claims that he suffered retaliation—including a Nissan-initiated raid, captured on video, of his home using a court order to seize company equipment—after raising whistle-blower complaints to the board about Nada running the internal probe into Ghosn’s alleged wrongdoing. Nada had been accused of alleged financial misconduct as well, but he had a cooperation agreement with prosecutors granting him immunity.

In one of the most audacious acts in recent business history, Ghosn staged a stunning escape from Japan in December while out on bail, being smuggled onto a private plane inside a music-equipment box during a $1.4 million operation financed partly with cryptocurrency. By fleeing, he forfeited 10 times that amount of bail money.

▲ The speaker case in which Ghosn hid while fleeing from Japan.

Source: Istanbul Police Department/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

While Ghosn has always maintained his innocence on the charges leveled against him and says he was the victim of a coup, it’s clear he enjoyed immense power at Nissan. Managers, even at the highest level, felt powerless to question him.

Accused of underreporting as much as $140 million in remuneration, misusing company funds and funneling millions of dollars more into secret units for his own benefit, Ghosn still has questions to answer about his years atop Nissan and the world’s biggest car-making alliance. Those questions won’t be asked by Japan’s legal system, which Ghosn says he fled because it is unfair.

“At the heart of it was the tragedy of a plot within Nissan,” Ghosn said in an interview from Beirut, where he lived from ages 6 to 17. “It didn’t take at all into consideration the well-being of the company.”

The arrests of Ghosn and former Nissan director Greg Kelly came as the company pursued greater production volumes only to see the global auto market sputter. Dogged by an aging lineup and overcapacity at 16 plants spread across the world, sales are now being hammered by the pandemic. In May, the maker of the Pathfinder SUV and Altima sedan reported a $6.3 billion loss, and its market value has more than halved since the arrests 21 months ago. Nissan is said to have spent more than $200 million investigating Ghosn.

The scandal also fueled a legal morass, with litigation underway from Amsterdam to Boston, where an extradition hearing will be held Friday for the men who allegedly helped Ghosn escape Japan. The trial of Kelly, accused of helping Ghosn violate Japan’s pay-disclosure laws, is set to begin next month in Tokyo. The saga that captivated the corporate world finally will get some sort of airing in court.

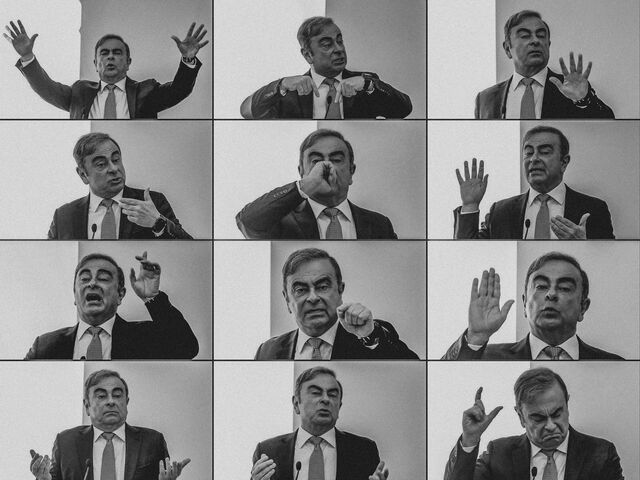

▲ Ghosn addresses a large crowd of journalists during a press conference on Jan. 8, 2020 in Beirut shortly after his escape from Japan.

Photographer: Joseph Eid/AFP via Getty Images

But these new revelations indicate that the turmoil within Nissan—and Nada’s apparent machinations—didn’t end with Ghosn’s downfall. They endured under the watch of Chief Executive Officer Hiroto Saikawa and his successor, Makoto Uchida, who took over eight months ago with a mandate to put l’affaire Ghosn behind the company. They raise questions about Nissan’s corporate governance and ability to emerge from the crisis.

Nissan has been saying since late 2018 that the allegedly illegal activities by Ghosn and Kelly were the sole reason why they were arrested and removed. “The cause of this chain of events is the misconduct led by Ghosn and Kelly,” for which the automaker found “substantial and convincing evidence,” it has said. Nissan declined to make Nada available for this story.

Grand Plans

Ghosn’s nemesis was born into a Tamil family in Malaysia as Hemant Kumar Nadanasabapathy, although he prefers to go by the shortened version of his surname. Nada grew up in the U.K., where he earned a law degree at Inns of Court School of Law. He also studied at Japan’s Chuo University on a scholarship.

After joining Nissan in 1990, Nada toiled in relative anonymity, working on commercial contracts in the U.K. and other matters. After losing out on the top legal position in Europe, Nada spent four years at Nissan’s headquarters before edging out the rival to clinch that job in 2012.

Although known for his eloquence and penchant for telling stories, Nada wasn’t a public figure like the executives around him who gave interviews and held news conferences. Apart from a few official pictures on Nissan’s website, public photos of the senior vice president are virtually nonexistent.

Nada returned to Japan in January 2014 to join the CEO’s office after his assertive management style caught the eye of Kelly, who ran human resources, legal and other corporate units. Nada inherited part of Kelly’s portfolio—as well as his office—and oversaw legal issues, compliance, security and other corporate affairs.

▲ Pedestrians walk across a footbridge in front of the Nissan Motor Co. headquarters at night in Yokohama, Japan on Jan. 9, 2020.

Photographer: Toru Hanai/Bloomberg

The position meant Nada essentially served as chief of staff to Ghosn and then Saikawa when he took over as CEO in 2017. From the 21st executive floor of Nissan’s Yokohama headquarters, Nada had a clear view of the inner workings of top management. It also meant he was privy to what was supposed to have been Ghosn’s grand finale as corporate chieftain.

As chairman of three automakers, Ghosn traveled relentlessly, shuttling between Paris, Tokyo and other countries on corporate jets. Having turned 64 in March 2018, Ghosn mulled a major legacy play. He wanted to bring the allied automakers under a single holding company and give back to Nissan some degree of parity with Renault, the lack of which long had been a sore point in Japan.

The French automaker saved Nissan almost two decades earlier by sending in Ghosn and providing a cash infusion that eventually made it the company’s biggest shareholder with a 43% stake. Yet by 2018, Nissan was making more cars and sending billions of euros in dividends to Renault each year. Despite that, the Japanese carmaker remained the junior partner, with a 15% stake in the French company and no voting rights.

Ghosn also had his eye on expansion, with early negotiations being held to add Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV to the holding company.

This grand alliance would sell everything from electric cars and Jeeps to Maseratis and hatchbacks. It would churn out more than 15 million vehicles a year, easily surpassing the 10 million-plus units produced by Toyota Motor Corp. or Volkswagen AG. The new car-making behemoth was supposed to have enough strength to survive the challenges facing the industry, take on upstarts such as Tesla Inc. and play a leading role in the future of transportation.

To pull it off, Ghosn needed top-notch CEOs to run each business. Although he would delegate more authority to each one, he would be the wizard behind the curtain, with each leader reporting back as Ghosn set broader strategy and made sure targets were being met.

▲ Lebanese police stand guard beside the house where Ghosn now lives in Beirut, on Dec. 31, 2019.

Photographer: Hasan Shaaban/Bloomberg

Plans were under way to build video-linked offices for Ghosn to oversee this empire. One would be in Beirut, within walking distance from the house Nissan bought and renovated for him. The other would be in Amsterdam, where the holding company would be based.

But back in Japan, there was a snag. Ghosn was starting to lose confidence in Saikawa, his handpicked CEO. Less than a year into Saikawa’s tenure, news broke that Nissan allowed unqualified staff to conduct safety inspections and certify the quality of vehicles produced in Japan. Profits also were declining.

Ghosn and Kelly began discussing replacing Saikawa with Muñoz, chief performance officer and head of Nissan North America, people with knowledge of their plans said. A Spanish national, Muñoz joined Nissan in 2004 and rose through the ranks in Spain, Mexico and the U.S.

Saikawa and Muñoz seldom got along. They argued at executive meetings and disagreed over Nissan’s strategy in China, a key growth market. In early 2018, it was becoming clear to a small group of insiders—including Nada—that Muñoz probably would replace Saikawa.

▲ Ghosn, second right, walks past Saikawa, seated left, at a news conference in Yokohama, Japan, on May 12, 2016.

Photographer: Yuriko Nakao/Bloomberg

By that point, Nada’s loyalties appeared to shift to Saikawa, people with knowledge of the matter said. Sticking with Ghosn would mean backing closer integration with Renault, something Nada bitterly opposed. He’d made enemies at the French automaker and believed that his influence and portfolio would become more limited if Ghosn made his vision a reality, people with knowledge of Nada’s plans said.

Almost from the moment Renault salvaged Nissan in exchange for the controlling stake, the French company’s power bred resentment inside the waterfront headquarters in the port city south of Tokyo. Nissan sits alongside Toyota as one of Japan’s most-recognizable global brands in an era when the influence of Asia’s second-largest economy is fading with the rise of China.

Nada and Saikawa calculated that the Japanese government had no desire to see Nissan become swallowed up in a sprawling holding company. They, in turn, targeted Team Ghosn for removal, the people said.

Saikawa declined to comment for this story.

Email Hacks

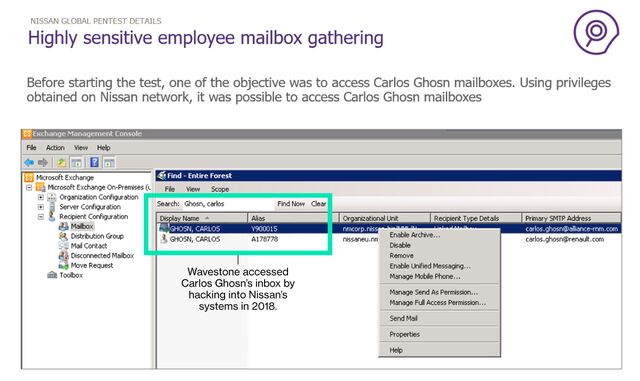

Sometime in early 2018, Nada hired the French company Wavestone to break into the computer systems of Nissan and its alliance partners, people with knowledge of the project said. The move surprised senior IT managers, who—along with CEO Saikawa and compliance staff—hadn’t been told of the project until they detected the intrusions, they said.

Ostensibly, the purpose was to test the company’s cybersecurity defenses, according to a Wavestone report seen by Bloomberg. But it also may have given Nada, who wasn’t usually involved in IT matters at Nissan, the ability to read Ghosn’s communications.

From March to August 2018, which overlapped with the period when Nada began cooperating with prosecutors, Wavestone gained access to several networks, including vehicle-production systems and plans for future models. One slide from the report shows how the security company was able to reach Ghosn’s email inbox.

▲ A slide from a report prepared by Wavestone showing how the security company was able to reach Ghosn’s email inbox.

Ghosn, who was known for demanding that his communications remain private, was told that “ethical hacks” were made in order to put in place safeguards to keep his information secure, people familiar with the report said.

It’s not clear what information Nada actually accessed or how he might have used what he learned. Yet by gaining entry into Nissan and alliance email systems outside of the organization’s information infrastructure, without allowing security staff to monitor Wavestone’s activities, any data would have become suspect. Not only could information be copied, it also could be planted or deleted. The integrity of data, including email inboxes, could be thrown into doubt. The credibility of such information could be challenged in court.

Sarah Lamigeon, a spokeswoman for Wavestone, declined to comment.

Then, in April 2018, Saikawa began to question publicly Ghosn’s push to make the alliance irreversible, saying he saw “no merit” in a merger between Nissan and Renault.

Around the same time or slightly later, Nissan’s lawyers shared information about Ghosn’s compensation scheme with the Tokyo Public Prosecutors Office. That led to Nada securing the agreement that granted him immunity. By October, Nada was busy gathering more evidence against Ghosn and Kelly.

Fearing Arrest

A month later, Nada persuaded Kelly to fly to Japan for an executive meeting, sending him a private jet. Nada also briefed two of his deputies—Passi, the global general counsel, and head of compliance Christina Murray—on what was about to happen.

The day before Ghosn and Kelly were arrested on Nov. 19, 2018, Nada sent Saikawa a detailed planning document on how to deal with the press and the fallout at Renault, which was kept in the dark, according to people familiar with the memo. Nada argued that Ghosn’s removal should be considered a fundamental change to the circumstances of the alliance.

▲ Saikawa speaks to the press in Yokohama on Nov. 19, 2018, shortly after Ghosn's shock arrest.

Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg

Renault’s right to nominate an executive as chief operating officer or higher at Nissan should be abolished, as should the agreement governing the relationship between the Japanese carmaker and Renault, Nada wrote, according to the people. He was making a play for greater autonomy for Nissan.

A spokeswoman for Renault declined to comment.

Muñoz, who was effectively the No. 3 executive at Nissan after Ghosn and Saikawa, was in Japan on the day of the arrests. Saikawa pulled Muñoz and a few other senior managers into his office and told the stunned executives that the chairman had committed crimes and was being arrested.

As news of Ghosn’s detention made headlines around the world, Muñoz found himself shut out of key meetings. A week after the arrests, Muñoz flew to Amsterdam for alliance-related meetings. Other Nissan employees told Muñoz they were being asked about his use of the corporate jet and his personal spending, people with knowledge of the actions said.

▲ José Muñoz, second left, and Yasuhiro Yamauchi, Nissan's former chief competitive officer, arrive at a meeting of the alliance's board in Amsterdam on Nov. 29, 2018.

Photographer: Jasper Juinen/Bloomberg

Muñoz then spent part of December in the U.S., where he was working on a deal with Waymo LLC, the autonomous driving company run by Google parent Alphabet Inc. Following negotiations in Silicon Valley, plans were set in motion to announce a Nissan-Waymo partnership in January at the CES trade show in Las Vegas.

But it appears there was another reason why Muñoz didn’t return to Japan. Bill Hagerty, the U.S. ambassador to Japan at the time, and Jorge Toledo Albiñana, Spain’s ambassador, expressed concerns about what might happen to Muñoz if he came back. Hagerty, who is running for the U.S. Senate in the November election, had close ties to Nissan and Muñoz because the automaker’s North America headquarters are based in his home state of Tennessee. Fearing arrest, Muñoz stayed away, people with knowledge of his thinking said.

Abigail Sigler, a spokeswoman for Hagerty, declined to comment, as did Fernando da Cunha Serantes, a spokesman for Toledo Albiñana.

Muñoz returned to Tennessee on Jan. 2, 2019, and was placed on leave the next day. He was handed a document promising a compensation package worth about $14 million, but only if he went to Japan to help with the investigations into Ghosn and Kelly. Nissan employees also took his laptop and mobile phone. Muñoz was told not to attend CES, and the Waymo deal wasn’t announced there. (It was disclosed quietly via press release five months later.)

Nada assigned Kathryn Carlile, one of his closest deputies, to oversee Nissan’s actions against Muñoz, people with knowledge of the matter said. After being pressed repeatedly to return to Japan and shut out of decision making, Muñoz must have known his career at Nissan was over. He quit a week later without severance, walking away from millions. He joined Hyundai in May of last year and hasn’t set foot in Japan since Nov. 28, 2018.

Dana White, a spokeswoman for Hyundai U.S., where Muñoz is based and runs operations for North America, declined to make him available for comment. “Mr. Munoz is grateful for his past experiences, but now as a top executive at Hyundai Motor Company, he is laser focused on performance and ensuring excellence at Hyundai,” she said.

Self-Examination

With Muñoz out of the way, Nada led a purge of other executives considered rivals or disloyal, according to several people familiar with his actions. Nissan assigned him a bodyguard, car and driver, and rented a second residence for him: a $12,000-a-month luxury apartment in Tokyo’s Roppongi district, one of the people said.

Nissan’s cooperation with prosecutors during 2018 was secret. Nada and a small group approached the Tokyo prosecutor’s office with information that apparently triggered the probe by its special investigations unit. Saikawa ordered an internal probe into Ghosn and Kelly. The heads of the compliance and legal departments, Murray and Passi, were assigned to lead the effort.

▲ Ravinder Passi

Source: Facebook

In late 2018 after the arrests, Nada sent Passi to the U.S., where he was under instructions to make sure the legal team there fell in line and cooperated with the internal investigation. Nada also told Passi and Murray that Latham & Watkins, the international law firm, would assist.

Latham & Watkins had been advising Nissan for years on ways to compensate Ghosn, but now they would be involved in investigating their own work. As the internal inquiry gained momentum, Nada held daily meetings with Murray and Passi. They learned more about companies set up in the Netherlands to purchase properties for Ghosn, pay alliance executives and handle tax issues.

Although Murray nominally was overseeing the investigation, Latham & Watkins seemed to be communicating more closely with Nada and Carlile, people with knowledge of the probe said.

Murray and Passi found themselves working around the clock. The Securities and Exchange Commission in the U.S., where Nissan also is traded, was conducting its own investigation into Ghosn and Kelly’s alleged wrongdoing, demanding documents and asking detailed questions.

Although it was clear by then that Nada—as head of the CEO’s office—was deeply involved in the allegations against Ghosn because of his cooperation agreement with prosecutors, he continued to manage the internal investigation, according to documents seen by Bloomberg and people involved. Ghosn, Kelly and Nissan eventually settled with the SEC in September 2019 without admitting or denying wrongdoing.

In the meantime, the Nissan loyalists—led by Nada—had gained the upper hand. In June 2019, Renault’s plan to merge with Fiat Chrysler and create a new auto-making giant with $190 billion in annual revenue was scuppered by Nissan’s opposition, even though the deal would have reduced the French government’s stake and restored Nissan’s voting rights in Renault.

Then, more revelations emerged.

Kelly, who was freed on bail a month after his arrest, told Bungei Shunju, a Japanese magazine, that Saikawa was overpaid by about 47 million yen ($440,000) after certain dates for a stock-linked payment scheme were changed. The CEO also was fully aware of Ghosn’s compensation situation, Kelly said. Saikawa had little choice but to open a separate line of inquiry into those allegations.

▲ Greg Kelly at his apartment in Tokyo on Feb. 6, 2020.

Photographer: Behrouz Mehri/AFP via Getty Images

After that, Murray and Passi discovered that Nada himself also had received inflated stock-based awards under the same program, according to people familiar with the matter and documents seen by Bloomberg.

Given that Nada was overseeing both the investigations into Ghosn’s wrongdoing and Saikawa’s pay issue, the general counsel was becoming increasingly concerned about conflicts of interest, the documents show. Serious questions about Nada’s credibility could be raised at any trial, and with Ghosn suing Nissan in the Netherlands over his ouster, Nissan’s defense against any claims could be jeopardized, Passi wrote in a memo.

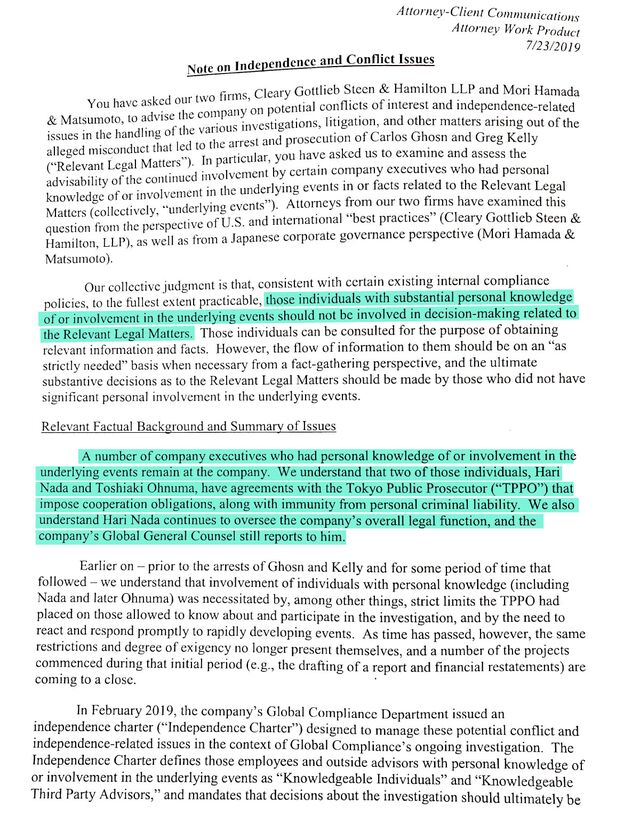

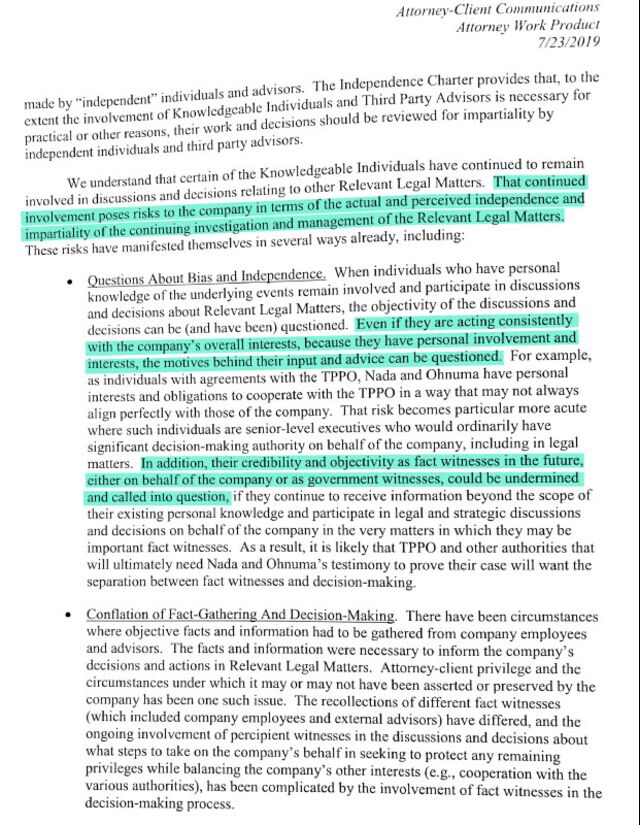

Passi hired two law firms, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP and Mori Hamada & Matsumoto, to review Latham & Watkins’s involvement in the internal probe and examine the roles of Nada and Toshiaki Onuma, another senior Nissan manager who has a cooperation agreement with Japanese prosecutors. Onuma also was implicated as the instigator of the inflated stock-linked compensation awards, although it’s unclear whether he received them, according to the documents.

The two firms delivered a four-page memo to Passi on July 23, 2019, highlighting the risks in keeping Nada, Onuma, and Latham & Watkins involved in the investigation into Ghosn. They should be “kept separate from the discussions and decision-making processes,” the lawyers wrote.

Latham & Watkins didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. Nissan declined to make Onuma available for comment.

No doubt knowing he was risking Nada’s wrath, Passi took the memo to Motoo Nagai, the director in charge of Nissan’s audit committee. Passi and Murray argued Nada should be interviewed by the committee to determine his role in the investigation. But Nagai apparently didn’t share the memo with other members of the committee, according to correspondence seen by Bloomberg.

Nissan declined to make Nagai available for comment.

A list that Murray drew up of 80 people implicated in the compensation allegations wasn’t shared in its entirety with Nissan’s directors. Nada told some members of the board that Latham & Watkins’s report into Ghosn would be enough, according to one email sent by Murray. Moreover, they wouldn’t be informed that Nada was apparently overpaid, the correspondence showed. Murray decided to quit and negotiated a severance package. Murray declined to comment on her time at Nissan.

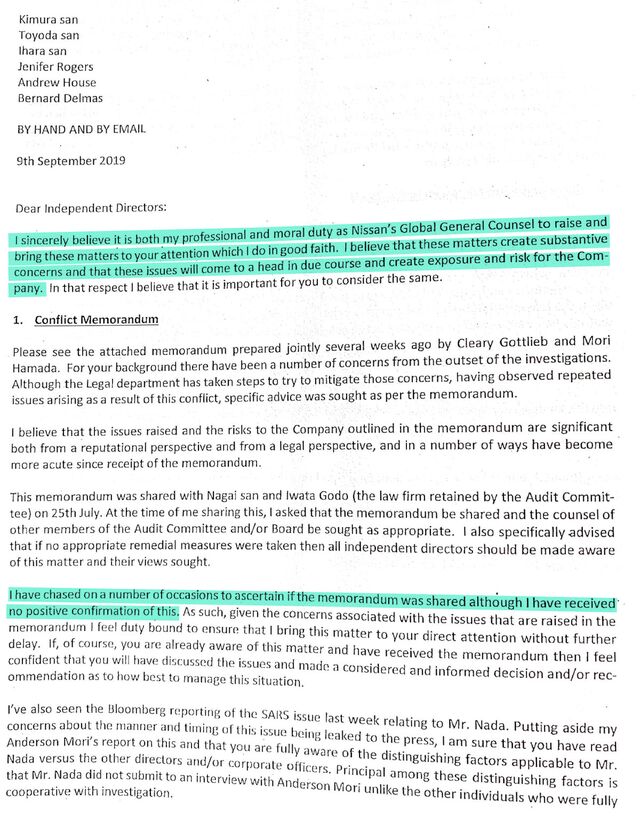

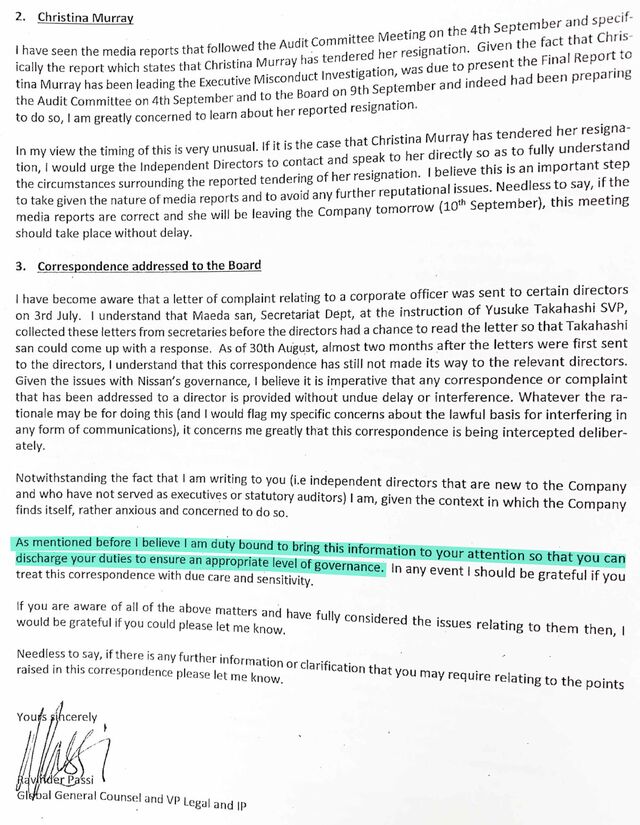

Frustrated, Passi decided to share his concerns about Nada, Onuma, and Latham & Watkins’ involvement in the internal Ghosn probe with independent directors. In a letter prepared for a board meeting on Sept. 9, 2019, Passi said it was his “professional and moral duty” to flag Nada’s involvement in the investigation and potential conflicts of interest.

“I believe that these matters create substantive concerns and that these issues will come to a head in due course and create exposure and risk for the Company,” Passi wrote.

The directors didn’t discuss the letter. Saikawa’s overpayment and the distractions it was causing were reviewed, however, and the CEO was ousted.

▲ Saikawa speaks at a news conference after resigning, in Yokohama on Sept. 9, 2019.

Photographer: Toru Hanai/Bloomberg

A week later, Passi was removed from parts of the Ghosn investigation. Neither Passi nor Murray, who had left Nissan by then, saw the final report submitted to the carmaker’s board. But the disclosures Passi made about Nada, first reported by the Wall Street Journal and New York Times shortly after the board meeting, seem to make an impact, with Nada’s title changed to senior adviser a month later.

“Although Nissan has found no evidence of inappropriate involvement by Nada in the internal investigation into executive misconduct led by former Chairman Carlos Ghosn and others, the change is aimed to avoid undue suspicion and to enable him to focus on important tasks for the company, such as forthcoming legal action,” Nissan said Oct. 19, 2019.

That same month, Renault CEO Thierry Bolloré was ousted by the French automaker’s board, just days after Nissan’s directors met to select Saikawa’s successor. As a representative of the Japanese company’s biggest shareholder, he had a seat on its board and raised concerns about the lack of action following Passi’s letters to Nagai and the independent directors.

▲ Thierry Bolloré shakes hands with Saikawa after an alliance press conference in Yokohama on March 12, 2019.

Photographer: Akio Kon/Bloomberg

“Nissan’s current challenges can only be overcome through fully transparent processes in compliance with both the law and international best practices,” Bolloré wrote in a letter to Nissan’s board. “The current state of opacity is no longer acceptable.”

Escape Velocity

Then, as 2019 drew to a close, Ghosn staged his spectacular escape.

Passi’s team had briefed new CEO Uchida on the potential conflicts of interest and problems with the Ghosn probe. In January, Passi, who reported to Uchida at the time, was sidelined as global general counsel. In March—as the coronavirus raged—the attorney was told by Nissan’s human resources department that he would have to return to the U.K. and take another position, effectively a demotion. Passi resisted, citing concerns about moving his family during the pandemic, people with knowledge of the situation said.

On May 28, people with court orders and apparently one attorney from a law firm hired by Nissan showed up at Passi’s home to seize his company-issued laptop and iPhone. On a smartphone video his wife, Sonia, took of the raid, Passi pressed them to identify themselves and say what they wanted. “My children are scared,” Sonia is heard saying in the footage, which was shared with several acquaintances, friends and Nissan colleagues. Passi’s family also suspected they were being followed by people hired by Nissan, his wife said in correspondence seen by Bloomberg.

▲ People with court orders showed up at Ravinder Passi’s home to seize his company-issued laptop and iPhone on May 28, 2020.

Although Nissan appears to have obtained an order from the Yokohama District Court to seize the devices, the procedure was an unusual way to reclaim company-issued equipment from an employee. It's also not clear why so many people—at least eight, according to the video—were needed in order to execute the civil order. In the video, Passi says he had offered to take the phone and laptop back to Nissan, and that the “absolutely disgusting” raid amounted to intimidation.

The former general counsel still works for Nissan and is now in the U.K., where he has recently filed a formal complaint with an employment tribunal, saying he was subjected to retaliatory action for making a whistle-blower disclosure and victimized by the company where he’s worked for 16 years.

Julian Fidler, Passi’s lawyer, declined to make him available for comment but confirmed that the complaint was filed.

“We do not comment on pending litigation,” Lavanya Wadgaonkar, a spokeswoman for Nissan, said in response to a list of questions and interview requests.

From the beginning, Nissan has insisted Ghosn and Kelly’s alleged misconduct—and nothing else—triggered their removal. The carmaker says it acted after learning there was “substantial and convincing evidence” the executives were acting illegally.

Nada will get a chance to make that case at Kelly’s trial, where he is scheduled to testify in January, more than two years after the arrests. Though he no longer has a leadership role, Nada appears to be involved in various Nissan matters ranging from legal issues and human resources to communications, according to people with knowledge of his activities.

The automaker that Nada sought to defend now finds itself in a perilous place, cutting costs and shuttering factories to conserve cash. Nissan now ranks seventh in global market share behind Hyundai and Ford Motor Co., according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Relations within the alliance remain strained just when the bulk of a global network is needed to weather the unprecedented challenges wrought by the pandemic.

▲ Ghosn sits in a vehicle as he leaves his lawyer's office in Tokyo on March 6, 2019, after being released on bail.

Photographer: Takaaki Iwabu/Bloomberg

As for Ghosn, he's considered an international fugitive by Japan and has yet to provide a comprehensive public defense of all the allegations against him. That may come when his book is published in November, first in French, followed by Japanese and English translations.

The homeland of his childhood is now gripped by economic and political instability. Ghosn wasn’t home when a massive explosion at Beirut’s port ripped through the city in early August, but the blast blew out the doors and windows of the house Nissan bought during his tenure.

The former chairman, who often hikes and visits historic sites with his wife, Carole, believes the grand auto alliance he built, the signature accomplishment of his career, is doomed.

“Each company is now in trouble,” Ghosn said. “I don’t think they know where they are going. There’s no more vision. In my opinion, the best people have left, or will leave.”

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2020-ghosn-nada-nissan/?sref=zQtH7y5q

https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2020-ghosn-nada-nissan/?sref=zQtH7y5q

Comments