Public anger over the handling of the Covid-19 crisis is palpable, and even before the crisis, internal criticism of President Xi Jinping within the Chinese elite seems to have increased. Photo: DPA

The

has starkly highlighted China’s strengths and weaknesses. Which other country has the political will and capability to quarantine a province of 60 million people? Which other country could build a new hospital in 10 days? But it also has to be asked: why were such drastic measures and Herculean efforts necessary in the first place?

It is now abundantly clear that the reluctance of local officials to convey bad news upwards allowed the virus to take hold and spread. In response to criticism that he had been slow to sound the alarm, the mayor of Wuhan, the city at the epicentre of the epidemic, said he had to get permission from Beijing to release such “sensitive” information.

China’s strengths and weaknesses both stem from a fact so obvious that it is too often ignored or downplayed: it is a communist country. Perhaps no longer in the classical ideological sense – although

has stressed the need for party discipline and his version of ideological orthodoxy – but certainly in the structure of the Chinese polity.

China is a Leninist state

that insists on absolute control over every aspect of state and society. Control is the primary value to which all other considerations are subordinate. If exceptions are made, they are tactical and temporary. Control gives a Leninist state the capability to take fundamental decisions and pursue them over the long term, with minimal discussion except within the top echelon of the party. It would have been nigh impossible in any other kind of polity to take and sustain the drastic policy shifts that led China to where it now stands.

Forty years ago, Deng Xiaoping took a cold, dispassionate look at his life’s work, decided it was flawed and in danger of failing, and drastically changed course, irrevocably changing China and hence the world. Which other leader in which other system could do that? Equally, however, China’s history since 1949 shows that mistakes in a Leninist system can have very tragic outcomes – the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution among them. Though thankfully not on such a scale, the Covid-19 crisis is also the consequence of the Leninist value system.

People take a selfie in front of a billboard in Shenzhen featuring China’s late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping on the eve of the 40th anniversary of China's “reform and opening up” policy in Shenzhen. Photo: AFP

But this crisis is also a symptom of a far more fundamental, perhaps existential, challenge facing China. In 2012, at its 18th Congress, the Chinese Communist Party acknowledged that the model – essentially based on a heavy emphasis on infrastructure development led by state-owned enterprises – that created China’s spectacular growth in the 1990s and early 2000s was unsustainable. To sustain a new norm of slower but still respectable growth over the long-run, a new model was needed.

The following November, the third plenum of the 18th Congress rolled out a plan that, at its core, envisaged: “The focus of the restructuring of the economic system … is to allow the market to play a ‘decisive role’ in the allocation of resources.”

These were bold words and, if implemented, would have created a new model for growth. However, implementation has been at best hesitant and subject to contradictory considerations. The market liberalisation that has occurred has mainly been in the financial sector.

It was not as if the Communist Party did not recognise the seriousness of the problem. More than other countries in East Asia, the party’s legitimacy rests on economic performance. Even the nationalism that it both uses and fears would ultimately ring hollow unless it rested on a foundation of continual growth.

But the Communist Party faces a fundamental dilemma. The essence of a Leninist state is the party’s insistence on control. The market, by definition, means less control. The choice between political control and market efficiency is of course not absolute. What was required was a new balance between control and efficiency. But what was that new balance to be? That was not clear.

By the time of the 19th Congress in 2017, it was still not clear. Most international commentary on that congress focused on Xi’s consolidation of power and his personal and global ambitions, but these were not necessarily its most significant aspects. More crucial for China’s long-term future was Xi’s redefinition of the “principal contradiction” facing China – that between China’s “unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life”, which he described as “increasingly broad”.

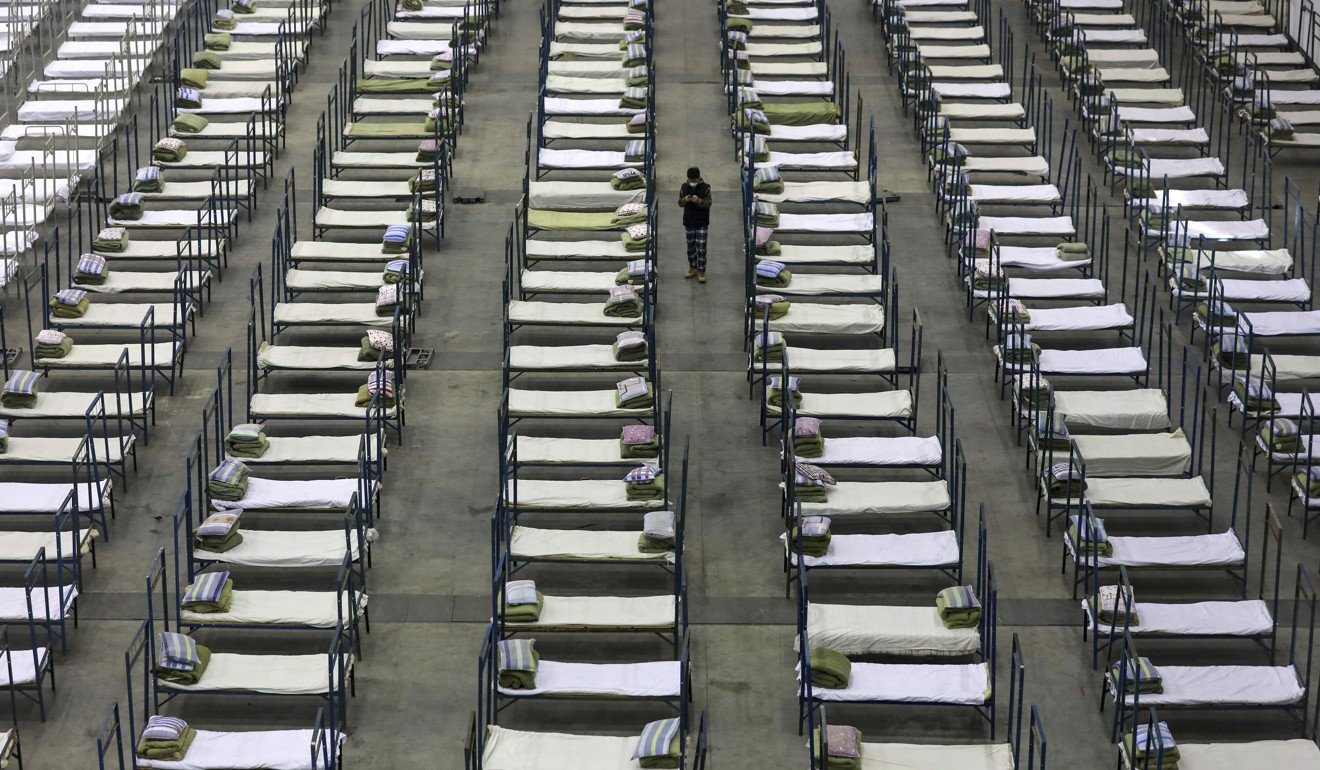

Public buildings converted into medical facilities for coronavirus patients in Chinese city of Wuhan

Rising expectations have set an extremely complex and lengthy domestic agenda. Dealing with that agenda will require a long time and immense resources. Exactly how long no one can precisely predict, nor can anyone predict exactly how many resources will be needed. However, the time available to deal with the issues is certainly not infinite, and while China’s reserves are huge, they are certainly not inexhaustible.

The central dilemma facing China can be simply stated: the political logic of a Leninist state contradicts economic logic, setting up a cycle that it is difficult to break. Continually replenishing resources over the long period needed to deal with rising expectations requires sustained growth, particularly in the context of a rapidly ageing population. Sustaining growth requires a new model based on greater economic efficiency. This, in turn, requires a new balance between party control and economic efficiency. Establishing a new balance necessarily entails risk. Mitigating the political risks and maintaining control requires growth to satisfy rising expectations. But growth requires a new model based on a new balance, and so on and so on.

Thus far, Xi has not found the will to take the risks needed to break this cycle with decisive action of the sort Deng took more than four decades ago. Economic policy since the 18th Congress has largely been a series of partial measures and improvisations – often brilliant improvisations, but nonetheless still improvisations rather than what is needed to decisively address the fundamental issues. Xi’s priority is clearly control.

The party’s caution and fear of loss of control is understandable. A big country that has undergone economic and social transformations of such scale and scope in an unprecedentedly short period of time is naturally internally roiled and deeply unsettled, and hence potentially unstable. An unstable China poses far greater challenges than an authoritarian China – not the least to the Chinese people and China’s neighbours; indeed, to the world.

A convention centre that has been converted into a temporary hospital in Wuhan, Hubei province, following the outbreak of the new coronavirus. Photo: AP

There is no practical alternative to party rule for China. The Covid-19 crisis has certainly dented the Communist Party’s credibility with the Chinese people. The party is probably still broadly popular – it has, after all, improved the lives of hundreds of millions of ordinary Chinese. Still, public anger over the handling of the Covid-19 crisis is palpable, and even before the crisis, internal criticism of Xi within the Chinese elite seems to have increased. At the same time, slowing growth and concern over social stability have pulled policy in contradictory directions. In 2017, the former governor of China’s central bank, Zhou Xiaochuan, warned that too many procyclical factors in the economy and excessive optimism risked “accumulating contradictions that could lead to the so-called Minsky moment”, or a market collapse.

The party is aware of the risk and had begun to deleverage. Nevertheless, under the pressures of slowing growth exacerbated by the trade war with the United States, China introduced a slew of measures intended to keep growth going – but which will also increase debt, on top of the debt accumulated while dealing with the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. The Covid-19 crisis will certainly further slow growth, and the new stimulus measures that are beginning to be rolled out will deepen the contradiction between the imperatives of growth and deleveraging.

As a Leninist state, China essentially has one national balance sheet – the Chinese private sector is ultimately subject to party control – which gives Beijing far greater scope for shuffling resources about to plug holes than normal market economies. But can even China indefinitely defy financial gravity? The former central bank governor did not seem to think so.

Sooner or later, the Covid-19 crisis will end. The party will then move decisively to address the serious flaws in China’s health care system exposed by this crisis. It must. Health care was already on the agenda set out at the 19th Congress. But will it go further to address the fundamental challenge of finding a new balance between control and economic efficiency? That is not clear. “Reform” in a Leninist state is always intended to strengthen and entrench the vanguard party. That was Deng’s fundamental goal; it remains Xi’s fundamental goal.

US President Donald Trump shakes hands with Liu He, China’s vice premier, during a meeting in the Oval Office of the White House in October 2019. Photo: Bloomberg

China will not fail. The party is an extremely adaptive organisation and inherits the experience of more than a century of political, economic and social experimentation. But the dilemmas and trade-offs now confronting China are more numerous, complex and daunting than those of earlier periods of reform.

The complexities are exacerbated by heightened strategic competition with the US. It remains to be seen if the pressures generated by the trade war will be sufficient to catalyse changes. China has taken some steps to meet American complaints, but implementation lies at the root of the matter. In a Leninist system, party privilege inevitably creates a less than level playing field. Some of the structural changes to the

that the Trump administration has demanded strike at the heart of the Leninist system. China cannot yield. Tensions will certainly resume.

In the long sweep of Chinese history, the times of maximum danger for ruling dynasties were those periods of internal uncertainty that coincided with periods of external uncertainty. We may be in such a time. Party rule and Xi’s position are not at immediate jeopardy. However, the Communist Party is approaching an inflection point, and some fundamental decisions cannot continue to be postponed indefinitely. Inflection points are breeding grounds for black swans. Some have already hatched.

Xi himself is something of a black swan. He is a “princeling” and the party is his patrimony. When party elders selected him as the new leader, they may have assumed that his was a safe pair of hands that could be trusted to clean up corruption, without shaking up the system too much. How wrong they were! The concentration of power around Xi seems to have reintroduced something akin to a neo-Maoist single point of failure into the Chinese system, whereby a single mistake can have widespread and perhaps catastrophic results. As the Covid-19 crisis illustrates, there is reason to question the accuracy and timeliness of information that is filtered upwards to decision makers.

Thousands of protesters gather in Central, Hong Kong in November 2019 to express gratitude to Washington for signing the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act into law. Photo: SCMP / K. Y. Cheng

The trade war is a second black swan. China seems to have underestimated President Donald Trump, and was clearly caught on the back foot by the change of attitude in the US. Hubris is not a Western monopoly. Hubris led Beijing to fundamentally misread the direction of American foreign policy, exaggerate China’s strengths, play down China’s vulnerabilities, and brush aside growing international concerns with certain aspects of Chinese behaviour. After the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, China seemed to have begun to believe its own propaganda about its inevitable rise and America’s (and the West’s) inevitable and absolute decline; Beijing may have overgeneralised from the Obama administration’s lack of stomach for confrontation after former president Barack Obama’s disastrous handling of crises over Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea and the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

Hong Kong is a third black swan. In itself, Hong Kong is not all that serious a matter to Beijing; its fate was settled in 1997 and it will eventually become just another Chinese city. But Beijing clearly misread the situation, and Hong Kong encompasses complex issues of Chinese identity that have bedevilled China since the late 19th century. Identity issues could have serious implications for China’s relationships with overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, Taiwan and beyond. Xi has claimed the support of “all Chinese” for his version of the “Chinese dream”. This board civilisational claim of privilege and authority creates the potential for trouble in Southeast Asia that could make Hong Kong seem only small beer. In the case of Taiwan, it has already been politically counterproductive and is potentially very dangerous. In the worst case, it could even lead to war with the US.

The longer fundamental decisions are postponed, the more likely is it that more black swans and other strange creatures may suddenly appear. We should not be unduly surprised if they do.

Bilahari Kausikan is the former permanent secretary of Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This article first appeared in his Geo-Blog with Global Brief magazine (Toronto) –

Comments