In an increasingly affluent society, fewer families are sending their children to study acrobatics, as a visit to the Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe School shows

- In an increasingly affluent society, fewer families are sending their children to study acrobatics, as a visit to the Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe School shows

It’s 5.50am, with just a faint purple light glowing on the horizon, when a group of children aged six to 15 march diligently towards their classrooms. At 6.15am, they begin lessons in Chinese, English and maths. At 7.50am, they stop for breakfast. There’s no time to linger, students must be clean and dressed by 8.30am, when they head upstairs to two spacious rooms on the first floor of an L-shaped building near the centre of Liaoning’s provincial capital, Shenyang. Here the real training begins. This is not academics, but acrobatics.

The boys and girls prepare to bend their bodies backwards until they can hold their legs with their hands. “One, two, three!” instructs Wang Ying, 47, head of the children’s team at the Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe School.

Where many of us would feel our bones crack long before reaching the final position, these kids can hold this near-circular inversion for more than a minute. Some of the youngest students are visibly in pain, tears rolling down their cheeks, but none give up or cry openly. At most, they break the silence with a sigh of relief when the position is released.

“We teach them all kinds of techniques, but flexibility is the most important thing at this age,” Wang says. “Even after two weeks of holidays it feels like starting from scratch, like their bones are welded together.”

Members of the Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe, including Guo Shenyu (top) and Sun Qiyue (middle), rehearse Panda: A Voyage Looking for a Dream at the Shengjing Grand Theatre. Photo: Zigor Aldama

The next pose requires laying their chins on the ground and bending their legs back over their shoulders until their toes touch the floor just a few centimetres from their noses. It seems to defy anatomy, but it’s clearly a more comfortable contortion: some even smile and chat.

Wang watches over the group with a straight face. She is a sturdy, modern woman with the sides of her head shaved. Firm but kind, she laughs with the children and uses encouraging words rather than the martial obedience demanded by those who trained her. Although she is no Soviet-style authoritarian, Wang stresses the value of “discipline, companionship and sacrifice, which keeps puberty’s rebellious character at bay”.

When the class ends, at 11.20am, she holds hands with some students and hugs others goodbye.

“They are very good kids,” she says, beaming. “They seldom moan or complain […] Our goal is getting them able to perform publicly after two or three years of training, and well before they get their official degree, which is granted when they complete the compulsory seven-year education.”

The school’s issue is not the students’ skills, but their precipitously declining numbers. According to the latest statistics, from the 2010 China Acrobatics Forum, the country has 124 troupes, 12,000 professional acrobatsand 100,000 people directly involved in the industry. Although those figures seem impressive, the state-owned school – which operates as a feeder programme for the Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe – has only 20 full-time students under 15 years old.

“When I started performing, acrobatics was one of the few ways we had to see the world,” says Tong Tianshu, a fit but grizzled 34-year-old performer and coach. “Thanks to this job, I’ve visited many countries and stayed in the United States for five years. But society has changed, and now travelling and studying abroad has become common.” Acrobatics as a passport to what lies beyond China is an outdated concept. “In the 90s, we could easily pick the best 60 children among many candidates every year, but now we’re lucky if we get 10 new ones a year,” Tong adds.

A student practises contortions. Photo: Zigor Aldama

Wang Xiao, deputy general manager of the troupe and school, says, “Even at the turn of the millennium we had 120 professional performers. We could divide them into three groups and engage in simultaneous shows. But now we are down to 40 and struggle to even split into two groups – we have to turn down many requests to perform abroad.”

It is a far cry from 1951, when the troupe was one of the first to be formed in the People’s Republic of China. The new government placed great emphasis on acrobatics as an emblematic art form of the nation, providing theatres for troupes in most major cities.

“No other troupe has had greater success,” says An Ning, the troupe’s director since 1997. “We’ve performed in more than 70 countries and 500 cities, and [won] over 40 international awards, including the first ever given to a Chinese troupe […] Ours is the most capable and influential troupe in China, ranked always among the top five.”

Chinese acrobatics can trace its roots back nearly four millennia but the art form blossomed during the Qin and Han dynasties (221BC-AD220), evolving from a simple exhibition of skills into a refined repertory of tumbling, balancing, plate spinning, pole balancing and rope dancing, known as “The Show of One Hundred Skills”.

“But thanks to the economic development of China, families are wealthier. Most want their kids to go to university. Acrobatic training can seem too hard, although it used to be even tougher. The one-child policy has also made it difficult to find new students,” says An.

An acrobat applies an ice pack to an injured knee. Photo: Zigor Aldama

Shan Dan, one of the troupe’s most experienced acrobats at age 36, points out the low wages aren’t helping recruitment drives. “My father works at a logistics company and my mother is a factory worker. After I graduated from the acrobatic school, my salary was higher than theirs. But, while wages in other industries have gone up, ours have stagnated. Now I need to have a side job to support my wife,” he says.

Coaches say many low-income families see acrobatics as a way to have their children taken care of. “They are well fed and receive an education,” Tong says. Across China, smaller, often private troupes recruit orphaned or “left-behind” children whose parents have migrated to cities for work.

Whatever the motivation behind their enrolment, for the best acrobats, theme parks such as Disneyland pay some of the highest salaries, often more than 10,000 yuan (HK$11,120) a month, but competition is fierce, Shan says. “Only a lucky few make it there,” he says.

Although Shan is a government-appointed “first-class performing artist”, he wouldn’t want his own children to follow in his footsteps: “I would respect his or her decision, but I would discourage it from the bottom of my heart. I’ve suffered two severe injuries, on the knee and the lower back, and I know how tough this job is.”

If that were not deterrent enough, there’s the career span to consider. “I hope to perform until I’m 40,” Shan says. “But the older I get I have to train harder and harder to yield poorer results.” Given the shortage of new talent, older acrobats have to stretch their careers for as long as possible.

The troupe performs Panda at the Shengjing Grand Theatre, in September. Photo: Zigor Aldama

Guo Shenyu, a 19-year-old acrobat, is suffering from a leg injury sustained during a performance and although she is not expected to make a full recovery for a few weeks, she is back training and will be on stage in a couple of days. “We need all hands on deck,” she says, with a broad smile and a shrug. “You have to be resilient, and smile even when pain blinds you.”

After a basic lunch of vegetables, chicken and soup, and a restorative nap, the students’ three-hour afternoon session starts at 2pm, focusing on jumps, balance and props. Some learn to kick bowls onto their heads, and they all love juggling clubs. Whatever the moves, the key to success is clear: repetition.

While the students complete their gruelling Monday to Saturday training on the first floor, down on the ground floor, the main stage is occupied by the troupe’s professional performers.

In one corner, a small group of girls rehearse an upcoming show – Panda: A Voyage Looking for a Dream – a humorous tale aimed at a young audience to be held in two days’ time at Shenyang’s Shengjing Grand Theatre, known as the “diamond” for its futuristic, angular design.

Practising riding a unicycle for the show, 14-year-old intern Sun Qiyuehopes to secure a job with the troupe when the year ends. “I guess I will earn around 2,000 yuan at the beginning,” she says, “but the salary increases according to our abilities.”

I enjoy the work. It’s tiring and painful, but there is no better reward than the long applause after a good show, and I’ve made good friends here

Qiyue’s parents enrolled her in the acrobatics school after a neighbour suggested it as an alternative to regular education. Her teachers praise her agility and cheerful personality and tout her as one of their most promising students.

“I enjoy the work,” she says, with a perennial smile. “It’s tiring and painful, but there is no better reward than the long applause after a good show, and I’ve made good friends here.”

Qiyue helps the clumsier Zhang Yongheng, a 13-year-old boy from Tongliao, Inner Mongolia, to improve his unicycle skills. He is one of the few present who had to pressure his family to let him join.

“I was always attracted by acrobatics,” he says, “and even though I know I will get the lowest of China’s formal education degrees and will never get rich, I wanted to learn the ropes and enjoy it.”

Juggling three wicker hats, Sun Mingjun, 16, is worried about his lack of formal education; students here receive far fewer classes than those at regular schools. “It makes me fear the future. But there is nothing I can do. I was never a good student,” he says.

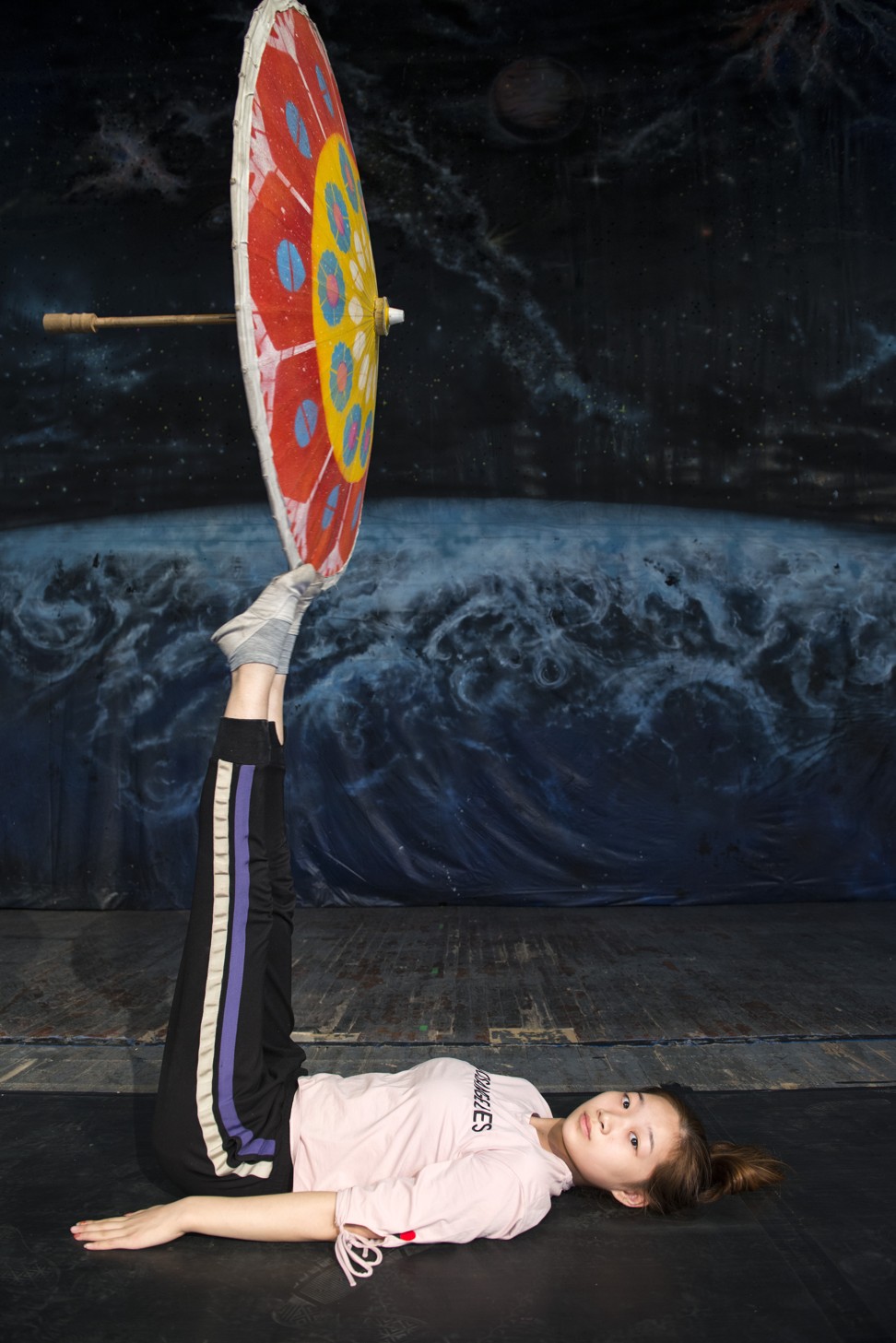

Beside him, playing with an oversized umbrella, 15-year-old Wang Junlin also recalls bringing home lacklustre marks from school. “I guess we are all here mostly because our parents thought acrobatics was a way out and we didn’t oppose them. Then we grew to love it.”

Wang Junlin balances a paper umbrella at the Shenyang acrobatic school. Photo: Zigor Aldama

On the right side of the stage, two 16-year-old girls separate from the main group and practise spinning up to four plates on each hand. They are here on loan from the Beijing Acrobatic Troupe.

“They needed more people for the show, which is competing at the China Wuqiao International Circus Festival [held in Cangzhou, Hebei province, in October], so we have been here for a month,” says Cai Yanqiu, one of the girls from Beijing. “As long as my marks are good enough, in Beijing, we can access university without gaokao [the entrance examination]. This is a good policy to get more recruits into acrobatics.”

The girls spin the plates for more than half an hour while they watch the eldest performers fine-tune every movement for another grand spectacle, Chasing the Dream, which the troupe will be taking to competition in Hebei. (Their efforts will be rewarded with a gold medal.)

“It introduces some spectacular elements, like acrobats riding three-seat bicycles, made exclusively for this show, without touching the handle bars,” says veteran army choreographer Li Chunyan, 46, who began her career as a dancer on a Nanjing military base. “I am getting older. I’ve suffered severe injuries in my lower back and legs and I don’t know how long I can stay on stage. So I started choreographing. The Shenyang Acrobatic Troupe contacted me and gave me some ideas for the show. They wanted to merge acrobatic and dance techniques to come up with something new. I’ve designed a modern, vigorous number, but it’s proving difficult to master.”

The problem is not technique, she says. “These children are amazing acrobats. They are very good at all things collective and they sacrifice so much to achieve perfection. We need to improve our skills in projecting emotions. That’s why I put a lot of effort into acting. The kids don’t open their hearts enough when they perform. They need to feel the music and understand that they are telling a story, not just jumping from one place to another.”

Zhang Yongheng trains at the school. Photo: Zigor Aldama

She is not alone in her criticism. Speaking at the 2010 China Acrobatics Forum, the head of the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe, Yu Yigang, reportedly said, “Some renowned foreign troupes have brought a new concept to the art of acrobatics. They have changed the performance formula by presenting a themed show with acrobatics as an element. With the predominance of this trend in the mainstream market, China lost its advantage.”

That’s why, during rehearsals in Shenyang, Li attaches special importance to facial expressions. Smiles, menacing glares and surprised expressions are welcome, but never blank stares. “It’s especially hard to achieve when you need to concentrate on not falling and breaking bones,” she says.

The next day, Panda dress rehearsals are taken to the main stage at the “diamond”. It is time to make sure everyone can meet Li’s standards. Despite Qiyue’s patient advice the previous day, unicyclist Yongheng is failing to coordinate with the others as they jump through a tower of hoops, and brings them all crashing down.

“Sometimes it’s better if we fail,” Tong jokes. “Because when we try again and succeed, the audience’s ovation is much bigger.”

He’s not wrong. On performance night, in front of about 400 children and their parents, a heavily made-up Tong is the one doing the falling, having missed a clear jump through the highest hoop. There’s a collective gasp. But his second attempt is successful, drawing applause and cheers from the audience.

Qiyue practises on stage at the Shenyang acrobatic school. Photo: Zigor Aldama

“Although we try to make shows 100 per cent safe, people across the world love the universal art of acrobatics because it’s spectacular, exciting, unpredictable and dangerous,” says An. “A minute on stage requires 10 years of practice and yet things can always go wrong.”

On stage and off, authorities are trying to restore acrobatics to its rightful glory, with new competitions such as Zhuhai’s China International Circus Festivalproviding more stable profits. But Tong believes salaries need to improve substantially to offer a viable career.

“The training is so hard that people will be interested in acrobatics only if it can guarantee a better quality of life. An elite sportsman can aspire to greatness and that’s what acrobats are lacking,” he says.

An struggles to conceal a grimace of disappointment at his art’s flagging legacy.

“The history of acrobatics can be traced back 3,700 years,” he says, sighing. “It’s China’s heritage and it needs to be preserved and encouraged.”

Comments