The US is no friend of Hong Kong protesters: it will abandon them, like the Kurds, as soon as it’s convenient

Pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong looks on during a hearing before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China at the Dirksen Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington on September 17. Photo: AFP

Ironies don’t come any sweeter than the US House of Representatives

of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act almost to the day America sold the Kurds

in Syria. That confluence of events is a tidy reminder of the old saw that nations do not have friends – they have interests.

of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act almost to the day America sold the Kurds

in Syria. That confluence of events is a tidy reminder of the old saw that nations do not have friends – they have interests.

Hong Kong’s earnest but naive students – thrilled to see some of their number in photo-ops with US Vice-President Mike Pence, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Senator Marco Rubio and Speaker Nancy Pelosi – would be well advised to take a few lessons from history.

The list is long of allies betrayed or students sacrificed on the altar of US realpolitik. Let’s take a little tour through a century of perfidy. Examples are not hard to find. It’s treachery bingo: spin the drum, put your hand in almost any decade and you are guaranteed to come up with a winner.

Let’s start with an oldie but a goody, the Spanish-American war. In Asia, it was fought in the Philippines. It was a brief fracas, with Spain defeated quickly in 1898, both there and in the Caribbean, where it began. But that did not end things. Many Filipinos had sided with the Americans against the Spanish, thinking they were fighting for national liberation, but then-president William McKinley’s government had other plans, and annexed the islands.

A jungle war prosecuted by the US Marine Corps dragged on for years and cost the lives of some 20,000 Filipino fighters and perhaps as many as 200,000 civilians (according to the US State Department’s own

.) One US commander at the time was particularly charming in addressing his troops: “The more you kill and the more you burn the better you will please me.”

.) One US commander at the time was particularly charming in addressing his troops: “The more you kill and the more you burn the better you will please me.”

Alfredo Stroessner (left) of Paraguay and Augusto Pinochet of Chile ride in an open car through downtown Santiago, Chile, during a visit by Stroessner in September 1974. Both Stroessner and Pinochet led repressive military dictatorships which benefited from US support. Photo: Reuters

Let’s spin the drum and pull out another, more recent one. The US-supported coup in 1973 against the elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile. Chile had copper. Multinationals wanted it. Allende wasn’t so keen. Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger didn’t like the look of that.

What followed the coup and Allende’s death was a reign of terror by Augusto Pinochet against leftists, unionists and, notably, students that resulted in up to 3,000 summary executions, the torture of tens of thousands, and scores of disappearances unsolved to this day.

Chile became part of the bigger, US-backed “Operation Condor” in the southern cone of Latin America, where even now Argentine mothers still seek their “disappeared” kids. A key victim group in this was students and teachers.

The bingo drum is chock full when it comes to Latin America. It was a cause célèbre for students in the 1980s. We marched to protest against US involvement in Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua. I generalise here in the interest of space, but anyone familiar with 1980s Central America knows that there was a consistent theme: just about every thumb-screw-twister or death-squad leader was in some way linked to, if not directed by, a US-client leader.

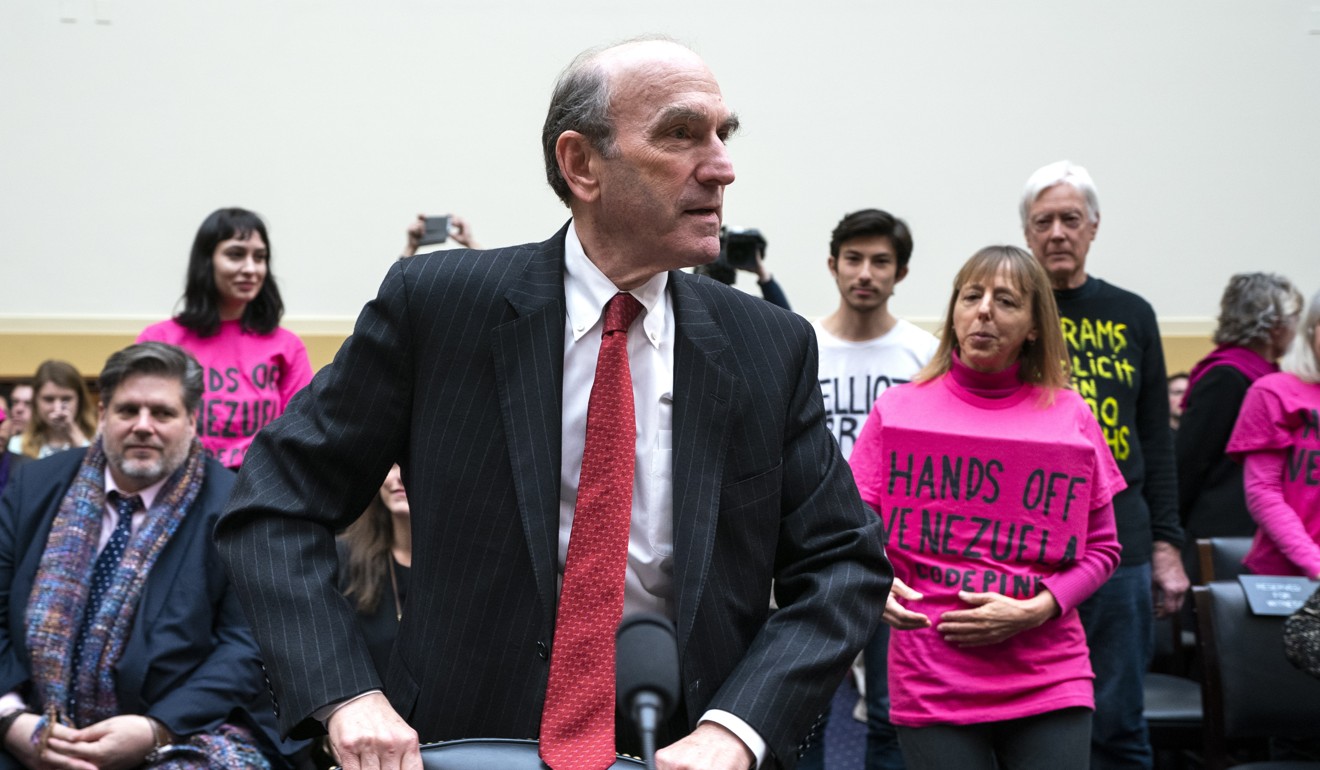

Activists with Code Pink protest against Elliott Abrams, US Special Representative for Venezuela, as he prepares to testify before a committee hearing. Photo: EPA-EFE

Here’s a fun fact: the Harvard-educated diplomat Elliott Abrams, convicted of lying to Congress over the Iran-Contra scandal of the 1980s, infamous for (inter alia) whitewashing a massacre in El Salvador, and a supporter of the Iraq invasion in 2003, was earlier this year given

by Pompeo on Venezuela, and said “it’s very nice to be back”.

by Pompeo on Venezuela, and said “it’s very nice to be back”.

But for our final bingo number, let’s come back close to home. Most people have never heard of Camp Hale, a remote army base high in the mountains of Colorado. The topography around Camp Hale is similar to that of Tibet.

As a result, the Central Intelligence Agency in the early 1960s used it as a secret location to train guerillas after China crushed the Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama fled in 1959. These fighters, many from the Khampa minority of Tibet, were by all accounts passionate, fierce and fearless. The story is nicely laid out in American writer John F. Avedon’s In Exile from the Land of Snows.

It’s not a pretty ending. The Khampa were dropped back into the Himalaya and were based in Mustang, a kingdom within Nepal that jutted into Chinese Tibetan territory, from which they could harass the People’s Liberation Army. But with the US opening to China in 1971, Avedon writes that “the CIA suddenly cut off support to the Tibetan guerillas”.

A deal had been done to sell out the Khampa. Nepal and India waded in to the mix along with China and the geopolitical game benefited everyone but those men trained in Colorado.

All of these stories, from the Philippines to El Salvador to Tibet, have a common thread. The US became involved for no motive higher than self-interest. This is what empires do. In the Spanish-American war, they feared Germany and France getting a leg up in global trade.

Central America was part of the first cold war. Tibet was intertwined with the “China card” that Nixon and Kissinger played against the Soviet Union.

So, students of Hong Kong, please take note (and Google “Kurdistan” for some up-to-date information). You are strategic collateral in the second cold war – and a very hot trade war. That may suit a short-term purpose, but the record shows it often ends poorly.

Tom Grimmer is a Hong Kong-based consultant who has worked, studied and taught in Greater China since 1985

Comments