How the flames of Hong Kong’s out-of-control protests are being fanned by a rigid mindset, leaving no place for those with an open mind

A fire burns on a road in Hong Kong on October 1. The violent protests are harming everyone, but perhaps worst of all for the long term, Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe and civilised place to do international business is suffering. Photo: Sam Tsang

I’m struggling to comprehend the lemming violence at the radical fringe of Hong Kong’s protest movement. I am struggling to see the dotted lines linking mounting street violence with any semblance of a plan.

My thoughts cast back to the months of student riots across Europe in the early 1970s. I remember a long discussion with the then-vice chancellor of our university, a formidable academic with a lifetime dominated by reason and logic, where he confessed: “I’m not equipped to deal with these upheavals. I’m trained to see both sides of an argument. In these circumstances, this is a fatal weakness, not helpful at all.”

Now, four decades later, I am that man. I’m not mentally equipped to deal with these upheavals. I suspect many across the senior levels of the Hong Kong government face the same predicament.

I was recently fascinated by work led by psychiatrist Leor Zmigrod at Cambridge University in the UK, exploring the mindsets of people who populate the extreme ends of the party and political spectrum. She was exploring this to dig to the heart of political polarisation around Donald Trump in the US and around the

in Britain, which is ripping the two leading political parties to shreds. Her thoughts shone fascinating light on our Hong Kong predicament, too.

In short, there is a type of mind that is associated with extreme partisanship, and that kind of mind is strongly linked with “cognitive rigidity”. As Zmigrod summarises in a paper in The Journal of Experimental Psychology: “People who are very attached to their parties display greater mental rigidity, relative to those who are moderately or weakly attached.”

Apparently, someone with a cognitively rigid mind is especially attracted to the clarity and certainty espoused by certain ideologies. Think football fans, or followers of religious cults, or the many other “tribes” that attract passionate followings. Think

and Mao’s Little Red Book. Think “do, or die in a ditch” Brexiteers. Think

.

Then think how the massive echo-chamber power of social media magnifies and reinforces those mentally rigid tribals – especially the adrenaline-pumping war game apps that have been lifted from their laptops at home and onto Hong Kong’s streets. There you find the lemming violence at Hong Kong’s radical fringe: youngsters willing to forgo all normal civilised or social activity over the past four months for a utopian millennial cause. This is the most thrilling ride of their lives.

The more cognitively flexible may be just as smart or idealistic as our utopian millennials, but they are no match for the tribal core at the heart of our current street warfare. A cognitively flexible person is unlikely to drift close to the heart of any tribe, nor likely to influence its members. He or she is unlikely to be willing to forgo the routine satisfactions of family life, or normal leisure, playing sports, reading books or simply weekend “malling” in exchange for tribal bonding over the barricades.

I see a couple of other relevant forces at work. One is the “men alone” phenomenon. Over the decades, I have frequently associated the world’s most violent conflicts with “men alone”. Think Islamic and other communities where males and females are strongly socially separated. Think the Johannesburg miners’ camps in the 1970s violence in South Africa. Think of the tribal males we call football fans. It seems testosterone, untempered by female moderation, can inflame violent instincts and run them out of control.

I have never sought scientific support for my “men alone” thesis, but having grown up with three sisters, and been married into a household of a wife, two daughters and a domestic helper, I am sure they have played a role in keeping those terrible testosterone forces at bay. That may be why gender balance on company boards is also a good thing.

The second force is what I call the coincidence of fracture lines. All societies are riven by differences. But only where the fracture lines created by these differences overlap do divisions in society become entrenched enough to trigger violence or serious instability.

Think of Northern Ireland, where Catholics were poor, filled manual labouring jobs and lived in the same impoverished neighbourhoods: protestants were rich, were the bosses and lived in their own affluent enclaves. Or think of apartheid South Africa. Then think of Hong Kong’s fracture lines, and how strongly they overlap.

A protester walks past anti-China graffiti at Hong Kong International Airport on September 1. Photo: Sam Tsang

How strongly these two additional forces have influenced the explosion of violence in recent months is hard to tell, but I am sure they have played a part.

It is one thing to identify “cognitive rigidity” as an important contributor to the incubation of violence in Hong Kong, but quite another to use the insight to help solve our crisis. It would be a start, perhaps, simply to recognise the powerful magnification of passions in the protesters’ chat sites, of the misuse and misinterpretation of events to create tribal myths, heroes and

.

If the

is to be tackled, then it is these chat sites that need to carry the more nuanced messages, no matter how strong the pressure towards ignorant polarisation.

One message that needs to be repeated and repeated is that the violence harms all, and takes us away from a solution, rather than towards it. It is physically harming many of our young protesters, perhaps scarring a whole generation. It is harming their families and the communities in which they live. It is harming

in our shopping malls and the people employed in them. It is dramatically harming

.

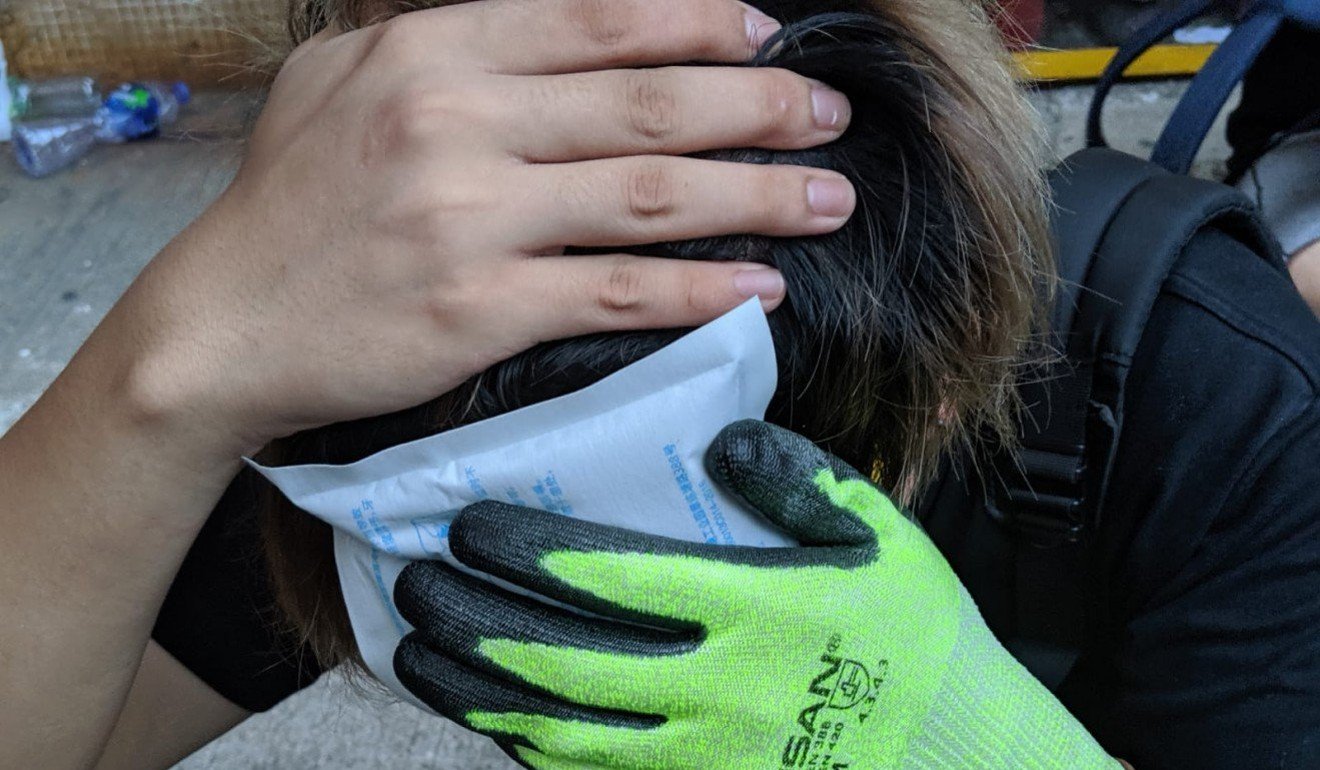

A protester covers his face after being struck by a round of tear gas on July 27. Photo: Handout

And, perhaps worst of all for the long term, it is harming Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe and civilised place for any company, from anywhere in the world, to do international business.

If our protesters believe their violence will win them independence, they can dream on. It is possible that the summer’s protests have succeeded in reopening the discussion on Hong Kong’s democratic future, but violence will slow that process, not speed it.

There is no doubt that the inept handling of this crisis has profoundly harmed the legitimacy of our administration, and of our hard-pressed police force. It has also made inevitable more direct involvement in Hong Kong by mainland officials. Healing is likely to take several years, but in due course it will come. More cognitive flexibility might help.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view

Comments