Hong Kong expects democracy, the Chinese don’t want it. It was clear from the start: historian Wang Gungwu

Hong Kong expects democracy, the Chinese don’t want it. It was clear from the start: historian Wang Gungwu

- The renowned academic Wang Gungwu reflects on unresolved tensions that have endured ever since the formulation of ‘one country, two systems’

- These span from Tiananmen Square to China’s failed attempt to make Shanghai its new financial centre

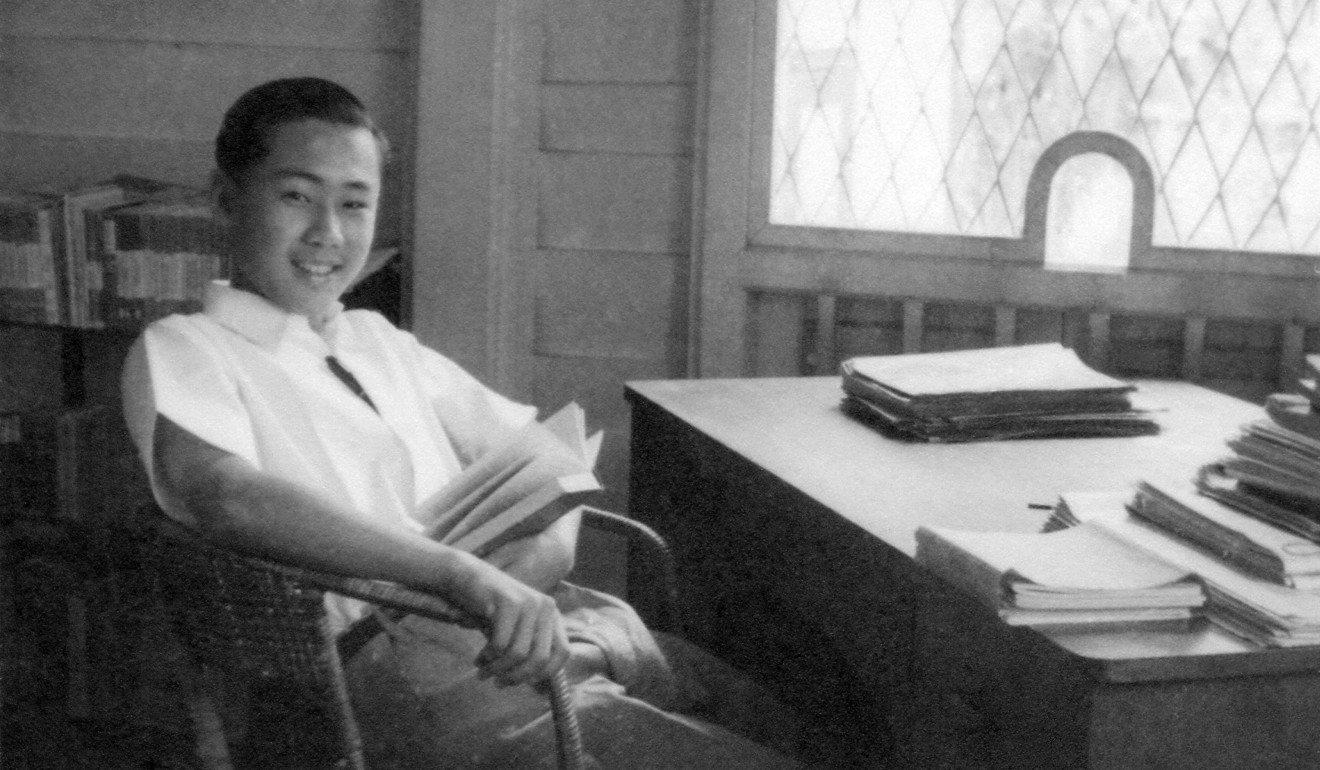

Historian Wang Gungwu. Photo: Handout

Historian

said yes to becoming vice-chancellor of the University of Hong Kong in 1985 partly because he wanted to see for himself the British colony’s transition into a special administrative region of China operating under the principle of “one country, two systems”.

He knew people in Hong Kong at the time, and understood that implementing the formula would prove difficult.

“Among those I knew, some were full of expectation and hope, yet also uncertainty and anxiety,” he recalled. “And some feared that things would go wrong.”

Under the framework devised by China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping in the early 1980s for Hong Kong after its handover by the British in 1997, the city was promised certain freedoms not allowed on the mainland.

Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1984, during one of their meetings leading up to the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the future of Hong Kong. Photo: AFP

But Wang said it was difficult to know at the time exactly what the balance between “one country” and “two systems” should be.

In an interview with This Week in Asia in

to coincide with the

, he said both Beijing and Hong Kong had been trying hard since the 1980s to make the “one country, two systems” principle work. But, over the years, the handling of difficult issues – including legislation to enact Article 23 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, to safeguard national security – had made the two sides increasingly distrustful of each other.

Tensions between Hong Kong and the mainland since the handover stemmed from the different expectations of democratic development in the city, said Wang, who continued to follow developments in Hong Kong after his decade-long stint at HKU ended in 1995.

“On the question of democracy, Hong Kong people have high expectations. The Chinese, of course, don’t really want democracy, and that was quite clear from the beginning,” he said.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Born in Surabaya, Indonesia, in 1930, Wang was raised in Ipoh, Malaya, before being sent by his family to the National Central University in Nanjing in 1947. In December 1948, on the eve of the Communist army’s victory in the Chinese civil war, he returned to Malaya via Hong Kong.

He completed his arts degree in 1953 at the University of Malaya, then in Singapore, went into academia and rose to head the Australian National University’s history department.

Wang Gungwu as a teenager in Ipoh, Malaya, in 1947 before he set off for Nanjing and passed through Hong Kong on a voyage to Shanghai. Photo: Handout

After his decade as HKU vice-chancellor, he helmed the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute for over two decades, and was chairman of the board of the university’s

School of Public Policy for 12 years. He is now one of a handful of distinguished scholars at the university given the title of University Professor.

Wang declined to comment on the current political crisis in Hong Kong, triggered by protests against the now-withdrawn extradition bill which would have allowed fugitives to be sent back to mainland China, among other jurisdictions with which the city does not have an extradition agreement.

Wang Gungwu with his uncle Wang Huwen in Shanghai, where he boarded a ship in December 1948 to return to Malaya. Photo: Handout

But he shared his views on what Hong Kong meant to China, and whether this might change.

He recalled that in 2000, in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis which hit Hong Kong hard, he came across experts in Beijing who had begun questioning the value of the city.

“I was very struck by that,” he said. “I could see that this was a genuine problem. If Hong Kong was not as valuable as it used to be, should everything else remain the same?”

He added that Hong Kong’s Basic Law existed to protect the “two systems” formula, though, ultimately, that formula was meant to benefit China.

HONG KONG’S STRONGEST CARD

“But the benefits [to China] have been getting fewer and fewer, particularly when all industries have moved to the mainland,” he said. “Hong Kong actually has no industry, it is purely a financial centre. If a financial centre runs into such difficulty as [Hong Kong experienced] during the financial crisis of 1997-2000, some of the shine is gone.”

The Chinese would have loved to move the financial centre to Shanghai, but they couldn’t do it. This is Hong Kong’s strongest card

Wang felt some on the mainland would have liked to see Hong Kong outdone.

“You know how hard the Chinese tried to create a new financial centre in Shanghai,” he said. “The fact that they didn’t succeed is not because they didn’t try.

“Hong Kong people know that the Chinese would have loved to move the financial centre to Shanghai, but they couldn’t do it. This is Hong Kong’s strongest card – the contribution of its financial services to China.”

He is confident that Hong Kong remains valuable to China, pointing to the Greater Bay Area plan that comprises Hong Kong, Macau and nine Guangdong cities to create a hi-tech innovation hub to rival California’s Silicon Valley. The cities under the plan will also link up with Guangxi province, which connects the country to Southeast Asia, ensuring that Southern China will have an increasingly important role in China’s economic development.

“Hong Kong should provide the kind of law, the kind of protection that makes people feel confident in Hong Kong,” Wang said. “All these are assets for China. I don’t think they are stupid to let these assets go.”

“Tank Man”, one of the iconic photographs to emerge from China’s crackdown in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. Photo: AP

TIANANMEN AND BEYOND

One of the world’s foremost experts on the Chinese diaspora, Wang was head of the history department at the Australian National University in Canberra when an HKU search committee approached him to succeed departing vice-chancellor Rayson Huang in 1985.

There was no lack of challenges during his decade at HKU, but what remains unforgettable is the 1989

crackdown in Beijing and its ramifications. Nearly eight weeks of student-led demonstrations against corruption, and calls for democracy had a profound impact on people in Hong Kong, then a British colony of 5.6 million people. On May 21 and May 28 that year, more than a million people took to the streets of Hong Kong in a show of solidarity with the protesters in Beijing.

Then, in the early hours of June 4, the People’s Liberation Army stormed the square. Hundreds – perhaps more than 1,000 – of protesters died. The crackdown shocked the world and especially the people of Hong Kong.

“I felt very strongly about this because when it happened, three student union leaders of HKU were in Tiananmen Square,” Wang recalled.

The students had taken with them funds raised in Hong Kong to support the Beijing protesters.

“When June 4 happened, they were still up there and we lost contact with them for several days. We didn’t know what happened. We were very fearful.”

The day after the crackdown, Wang was scheduled to speak at a graduation ceremony at the Chinese University’s Chung Chi College.

“I had a sleepless night,” he recalled. “The moment I started to mention the fact that our students were involved, tears welled in my eyes. I couldn’t help myself.”

Wang Gungwu pictured when he was vice-chancellor of the University of Hong Kong in the 1990s. Photo: Handout

Fortunately, his students were all right. A few days after the crackdown, they contacted the university and returned to Hong Kong.

Wang said the Tiananmen Square crackdown affected how Hongkongers felt about Beijing and their disillusionment was very strong.

The fear of

prompted a wave of emigration, with thousands queuing outside foreign consulates for application forms to leave Hong Kong.

PAST TO PRESENT

After the crackdown, Wang was appointed to the Executive Council, the city’s top decision-making body.

He took part in two key moves that were regarded as morale boosters for Hongkongers: the expansion of places for higher education and building a new airport.

In the 1989-1990 academic year, only about 7 per cent of students aged between 17 and 20 received a university education. This rose to 18 per cent by 1995.

The Chinese government and many in Hong Kong were very suspicious of the reasons why the Hong Kong government was going to spend all of its reserves on the airport

Wang recalled that the decision to build a new airport in Chek Lap Kok – the largest project ever undertaken in Hong Kong – had proved controversial because of a lot of misunderstanding. He said although everybody agreed that Hong Kong needed a new airport to replace the overcrowded old Kai Tak Airport, the question was, who would pay for it? The new airport and associated infrastructure cost HK$155 billion, with a third coming from private-sector participation in the form of commercial lending and key franchises at the airport for air cargo handling.

Wang Gungwu at the Robert Black College for HKU Swire Scholars in 1987. Photo: Handout

“The Chinese government and many in Hong Kong were very suspicious of the reasons why the Hong Kong government was going to spend all of its reserves on the airport, with foreign companies, including British companies, getting the contracts,” he said. “I think it was not such a cynical decision. It was quite a sensible decision not to delay any further.”

The new airport opened in 1998 and has become the lifeblood of Hong Kong’s economy.

Looking back at his long career, the eminent scholar said he never set out to be a historian. “I started [off being]very fond of literature and wanted to be a writer,” he said. “But I realised later I was not good enough to be a good writer. Then I found that learning about the past helped me to understand the present.

“I became a historian in order to know the world today, to better understand my own times, my own world and even my friends – to understand them better, I needed to know the past.”

WANG GUNGWU’S CV

Age: 89

Place of birth: Surabaya, Java, Indonesia

Education: Bachelor of Arts in history, University of Malaya, Singapore, 1953; Master of Arts, 1955;

PhD, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1957

Career:

Dean of the Faculty of Arts, University of Malaya, 1962-1963;

Head of history department, Australian National University, Canberra, 1968-1975, 1980-1986;

Vice-chancellor of the University of Hong Kong, 1986-1995;

Director of East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore, 1996-2007 (formerly known as Institute of East Asian Political Economy);

Chairman of the governing board of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, 2004-2017

■

Comments