How Jet Li turned the Shaolin Temple into a kung fu cash cow for China

- Paid just 1 yuan per day, the martial arts superstar was stunned to find ‘there were no monks’ when he turned up to shoot 1982 film

- ‘After the movie came out the Shaolin Temple became very popular. A lot of tourists, a lot of martial arts schools’

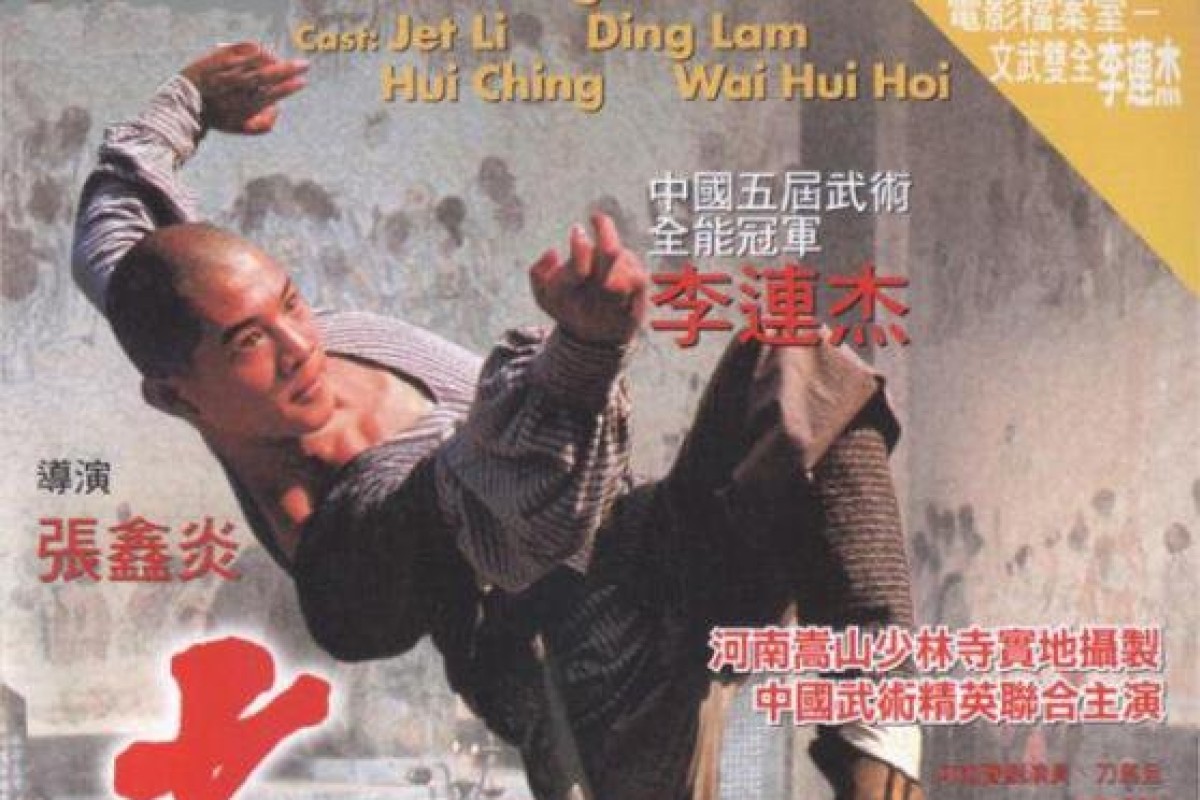

The DVD cover for Jet Li’s The Shaolin Temple. Photo: Twitter

The 1982 film The Shaolin Temple famously launched the career of martial arts superstar Jet Li. But perhaps less widely known is that it also essentially created Shaolin kung fu as we know it.

The Shaolin Temple is now a Unesco World Heritage Site and the heart of tourism in Henan province in central China. Scores of martial arts schools lie on a mountain; ticket sales bring in tens of millions of dollars each year; the temple is now a commercial empire operating more than 40 overseas companies; and international media has even dubbed its abbot, Shi Yongxin, “the CEO monk”.

But when a film crew from Hong Kong’s Chung Yuen Motion Picture Company turned up in 1980, they found an abandoned site in disrepair after decades of neglect.

“When I was working in Shaolin there were no monks ... only three monks ... and they had just finished the Cultural Revolution,” Li said in an interview with Kung Fu Magazine in 2001. “Not a lot of people knew about the Shaolin Temple. After the movie came out it became very popular. A lot of tourists, a lot of martial arts schools.”

Monks practise kung fu at Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, Henan province, in April 2016. Photo: Xinhua

It was the first martial arts film made in China and the first filmed on location at the Shaolin Temple, an ancient Buddhist monastery that is revered as the birthplace of China’s most famous wushu style.

Monks had supposedly practised fighting styles there for 1,500 years based on animal movements and birds – this became known as Shaolin kung fu, a comprehensive cultural and spiritual system, which strengthens the inner self as demanded by Buddhist doctrines.

But all that heritage was wiped out when Communist Red Guards attacked the monastery in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution as part of their campaign against religion. Ancient artefacts were destroyed and the monks who lived there were beaten up and ridiculed.

China had condoned violence against a site that was sacred for Buddhists and martial artists, but just two decades later they allowed the monastery to be used in three films starring Li.

China was looking to boost its weak economy by edging towards business deals with other countries, and partnering with Chung Yuen turned out to be a masterstroke.

Set in the seventh century, Li – then known by his birth name, Li Lian-je – played Jue Yuan, who travels to the Shaolin Temple to learn martial arts so he can avenge his father’s death at the hands of the evil Wang.

It took two years to film, with production methods fairly primitive given the dilapidated setting. Production on the film was also halted for six months when Li fractured his leg while filming one of his jaw-dropping martial arts fight scenes that would come to help make him a household name and a multimillionaire.

But just as jaw-dropping was his recent revelation in an interview on “A Date With Luyu” that he was paid just 1 yuan per day while shooting the film, making around US$750 in total.

“Remember, I’m just a normal guy, I’m lucky, learning martial arts. Now I’m lucky making films,” Li said in another interview with Kung Fu Magazine. It’s quite a contrast with the US$350 million fortune he has said he will leave to his wife.

Despite those tough conditions, Li has said that filming the first Shaolin Temple was still like being on holiday.

“The best part about making that film is that we didn’t have to train any more,” he said. “Even though we were waking up at five or six to get to the set, and shooting from eight until sunset, it was nothing. This was relaxing. Didn’t we have to fight all day? Sure, but this was nowhere near as tiring as wushu class. In fact, after we finished the day’s shoot, we’d go out again and play soccer or basketball.”

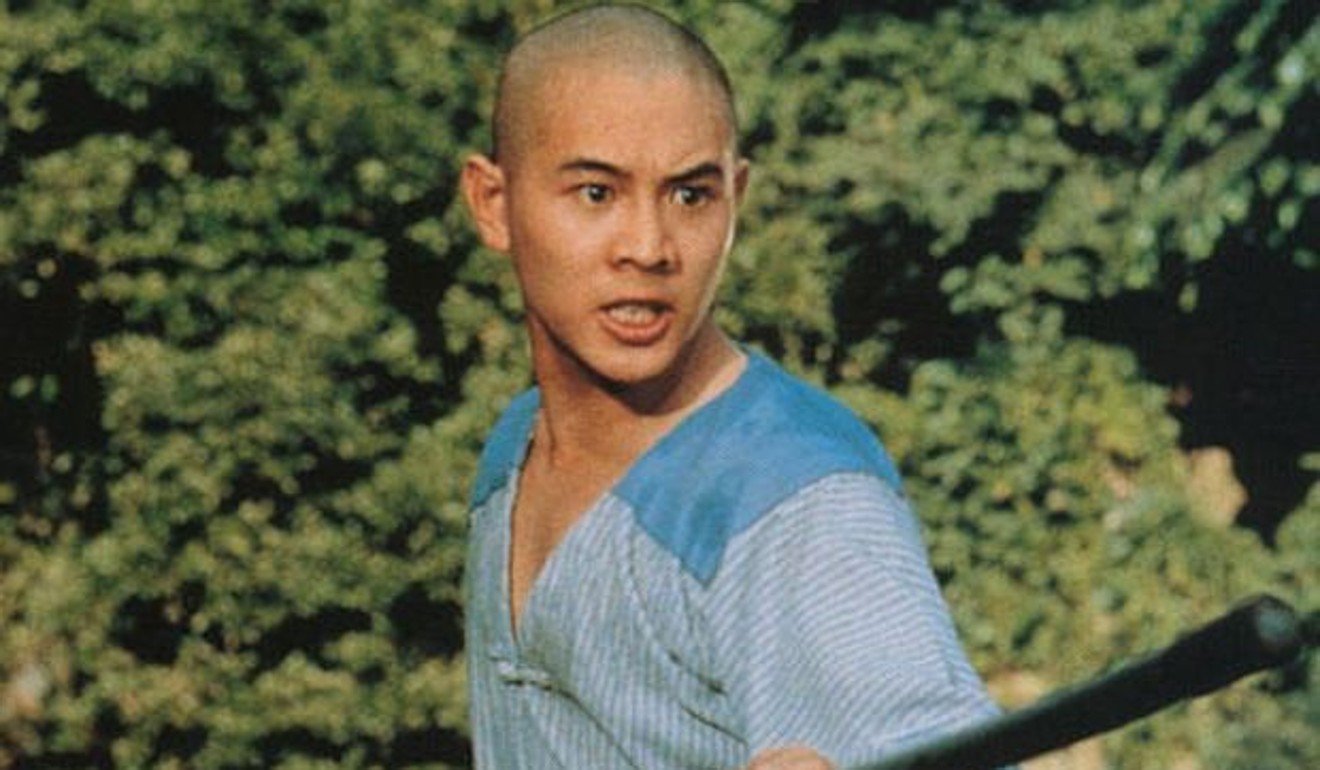

Jet Li’s career took off after his turn in The Shaolin Temple. Photo: Twitter

The monastery’s ancient murals provided a vivid and authentic backdrop that delighted film-goers, 700,000 of whom flocked to cinemas to watch it in Hong Kong upon its winter release.

With interest in the Shaolin Temple’s history reawakened, a transformation was sparked and China had a new tourism cash cow to milk.

The film was so successful, Li Lian-je changed his name to Jet Li because theatre owners thought his birth name was too long.

Jet Li’s The Shaolin Temple helped make martial arts mainstream. Photo: Twitter

“I remember when I was young, I really wanted to promote martial arts,” Li said. “In the 1970s I already had travelled to different countries, doing demonstrations. In the 1980s I started by making one movie. My eyes just opened.

“I saw a lot of people watching the movie and they started liking the martial arts. Then I said, why not just continue making movies and through the movies give out more information. I really want the martial arts to help the people.”

In this 2012 photo, visitors walk past as young monks offer prayers outside the Shaolin Temple. Photo: AP

Two Shaolin Temple sequels followed – Shaolin Temple 2: Kids from Shaolin in 1984 and Shaolin Temple 3: Martial Arts of Shaolin in 1986, for which Li was still paid peanuts. He hated his experience on the sequels, with working conditions poor on the second film – “we lived like peasants” – while he fell out with the director of the third film, La Ka-leung, because of the Hong Kong filmmaker’s treatment of crew members from mainland China.

Li considered quitting the business, so miserable was his experience, but Hong Kong film companies knew they had a star on their hands so they convinced him to keep going with big offers, and a star was born.

As for the Shaolin Temple, there was no stopping that commercial juggernaut.

Comments