China’s crowded labour market is making life tough for foreign workers and new graduate ‘sea turtles’- SCMP. 13 Feb 2019

China’s crowded labour market is making life tough for foreign workers and new graduate ‘sea turtles’

- Overseas-trained talent known as ‘haigui’ are no longer seen as having an advantage over locally educated employees

- In the 40 years since opening up began, a total of 3.13 million sea turtles or 83.73 per cent of the Chinese students who graduated abroad have returned home

Demand v Supply

With the Chinese economy slowing, concern has increased

among Chinese policymakers about the outlook for employment, since ensuring a

sufficient number of new jobs is seen as a necessary ingredient in maintaining

social stability. Employment was the top priority set by the the Politburo last

July when it shifted its economic policy focus to stabilising growth, and this

in turn lead the government to enact a series of policies to counter rising

joblessness. This series explores the employment challenges faced by different

segments of the Chinese economy, and this second instalment examines the issues

faced by Chinese students returning from studying overseas, as well as foreign

workers.

As the clock struck 11pm on a Wednesday night in late January, Peter Chen finally left his office in northwest Beijing. He had been researching the perception technology used in self-driving cars since 10am that morning.

Chen, a native of Yunnan province, is a recent returnee to China, having studied for bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science in Hong Kong.Since returning to China, Chen’s career path has been a winding one.A start-up venture he launched – a travel planning app – never got off the ground, so he spent a year teaching himself the engineering of autonomous vehicles, before landing a job at one of China’s internet giants.But that has not been an easy road to travel either.

Chen works long hours for low pay. His monthly salary is less than half of what he expected, and he regularly puts in 13-hour shifts. Of the 30 people in his team, most are local graduates, with only five having studied abroad.

“I am always thinking about what exactly are the advantages of being a haigui nowadays,” Chen said. “In terms of technological know-how, mainland graduates are not lagging behind, but are even stronger.”

Haigui is the Chinese term to describe people who return to China having studied abroad. It sounds like the Chinese word for sea turtle – and like their migrating namesake, these returnees have often travelled great distances to come home.

The term used to be synonymous with China’s elites. Forty years ago, when he started China’s opening-up process, paramount leader Deng Xiaoping made a strategic decision to send Chinese students and scholars overseas to learn new technologies and management skills.

Haigui would go on to play pioneering roles in modernising the Chinese economy and found many well-known Chinese technology companies, including Sohu, Baidu and Sina.

But as China’s economy developed, more families were able to afford to send their children to study abroad and the haiguigradually became less exceptional among a highly-educated and modern Chinese workforce.

In 2017, a record 480,900 Chinese students returned to China having studied overseas, according to data from the Ministry of Education, an 11.19 per cent increase from 2016.

Of these, nearly half held a master’s degree or higher – 14.9 per cent more than the corresponding figure for 2016.

In the 40 years since opening up began, a total of 3.13 million “sea turtles”, or 83.73 per cent of the Chinese students who graduated abroad, have returned home.

In a separate survey by the recruitment website Liepin.com released in January, 80 per cent of returnees in 2018 expected an annual salary above 200,000 yuan (US$29,652).

In reality, more than half of respondents were earning less than 100,000 yuan, a sign that returnees have lost their edge over domestic graduates.

“A couple of years ago I would have said the returnees were better employees,” said Aurelien Rigard, the co-founder of Shanghai-based technology company IT Consultis.

“Today, I am not convinced they are much better. I am very impressed by the quality and work ethic of the home-grown talent.”

Facing fierce competition from a more competitive employment market, people like Yunnan province native Chen, with his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science from Hong Kong, have struggled to find the work they want.

“The company will not treat me differently because I am a returnee,” Chen said. “Language or communication skills might give me a competitive edge, but in the world of computer engineers, that isn’t a big deal.”

Kimi Fei returned to Shanghai in August 2018 after obtaining a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree from the prestigious Stephen M Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, but like other sea turtles, found he was swimming against the tide.

Despite his illustrious education, Fei struggled to find work with a Chinese firm, which was his preference, and he was forced to broaden the search and found work with a multinational commodity trader, working as a strategic investment associate.

“The word haigui has lost its historical significance,” he said, adding that Chinese firms are now more keen to hire from top local universities.

With a slowdown in the Chinese economy, this is becoming even more pronounced – especially in the fields of finance and property – according to a study by the consultancy firm PreTalent.

When job hunting from the United States last year, Fei did not see any Chinese real estate companies recruiting on campus.

“In previous years, developers such as Huaxia Happiness and Vanke spent a lot of money on luring MBA students from American business schools,” he said.

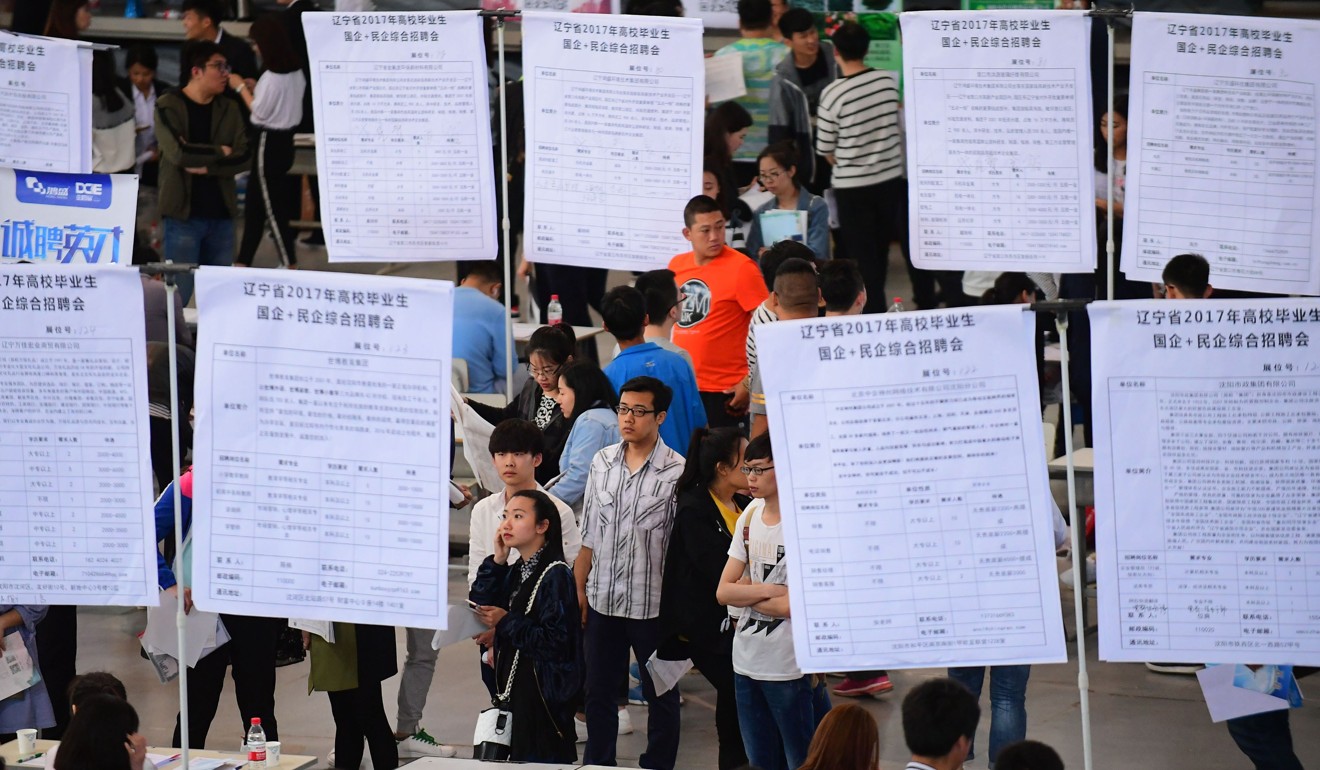

The number of China’s graduate students will reach 8.34 million in 2019, more than ever before, said Qiu Xiaoping, a vice-labour minister, in mid-January.

“Chinese nationals studying abroad would have often graduated and got a job abroad, but a lot are wanting to go back to China, because that’s where the action is,” said John Mullally, regional director for financial services in South China at recruitment company Robert Walters.

Whereas those that stay overseas may improve their language and technical skills, particularly when it comes to structuring financial deals, they will not have a network in China, which is vital for many client-oriented finance jobs.

“Previously they would have stayed abroad until they made vice-president; at that point they’re not cheap. But now they’re coming back at the analyst level,” Mullally added.

The fiercely competitive labour market is also creating challenges for foreigners in China – for both companies and employees.

A report released by LinkedIn and Bain & Company in December last year found that 40 per cent of business leaders who began a new job at a local company in the past five years transitioned there from a multinational company.

“Local companies are winning more talent from multinational corporations,” said Stephen Shih, a partner at Bain.

Part of the reason is the elongated chains of command at international firms, meaning a manager or director in China might have to report to an Asia-Pacific superior, or even back to the main headquarters in London or New York.

“If there’s a lack of urgency in the head office, your request might sit there for a few days, then that opportunity in China has moved on. Things happen so fast here,” said Ker Gibbs, the president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai.

“Chinese organisations get that. You walk into the CEO’s office, get a decision and walk out,” Gibbs said, adding that competing for talent is the “new battleground” for foreign firms in China.

For foreign workers, things are becoming trickier too – the opportunities are narrowing, particularly in the middle-management areas.

Companies in China, both foreign and Chinese, are actively “localising” the workforce, again due to the availability of highly-skilled Chinese talent.

“In conversations on the topic, members do mention a growing preference among companies for recruiting local talent with international education, rather than junior expat profiles that may leave the country one day,” said a spokeswoman for the European Union Chamber of Commerce in Beijing.

Those with very specific technical skills are valued and are often found in the upper echelons of companies, and there are more opportunities available outside the saturated hubs of Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen.

“If you’re a seasoned professional, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t have opportunities [in China]. The question is, are you willing to move to Hangzhou, Chengdu or Xian to manage an Alibaba business unit, or do you only want to live in Shanghai?” said Richard Brubaker, the founder of Collective Responsibility, an advisory firm based in Shanghai.

Alibaba is the owner of the South China Morning Post.

According to Gibbs, there are also plenty of foreign entrepreneurs in China, but the economy and the workforce has matured to the point where if you do not have an excellent business plan and execution strategy, it is increasingly difficult.

“When I first came to China in 1985, it needed everything – and a lot of it. When you think about building a business in that environment, for almost anything, if you could get it to sprout you could get it to grow. In 2019, we are in a completely different situation,” Gibbs said.

It is believed there are fewer Western start-ups in China, and while the exact figures are difficult to come by, those that have survived tend to be made of sterner stuff.

Rigard launched his technology company in Shanghai eight years ago, and since then, the French entrepreneur has seen his venture grow to 70 people, 40 of whom are based in China, with 30 in Vietnam.

“There’s now a different category of entrepreneur,” he said. “People used to come to Chinese soil for visa purposes, lots of them started a business in China without researching it. This is not the case any more – you must have experience.”

The technology space in which he operates, having launched e-commerce channels and platforms for mainly international retail clients who wish to sell in China, has become fiercely competitive.

Unlike local companies, his business does not have access to bank loans or, indeed, much of the information that is released through official channels.

“You are always working hard to live to fight another day,” he said. “You realise that other people lost their business due to bad luck, not because they weren’t as good as you.”

People like Rigard and recent returnee Chen are operating in a new China – a jobs and business market as vibrant as anywhere else in the world, with new and modernising industries that will require the cream of global talent.

For Rigard, it means navigating the “bamboo ceiling” said to face foreign businesses in China, while Chen feels he made the right decision to return to China despite long hours.

Liepin.com estimates that the number of artificial intelligence engineers with overseas education shot up 47.83 per cent in 2018 compared to a year earlier.

Chen, who rejected overtures from European car companies, is one of them.

“Chinese companies might already be ahead of their Western peers in some areas of autonomous driving,” he said. “And in a Chinese company, I can have a strong influence over research and development.”

The third instalment of this series will examine the issues facing the life services or “gig” economy.

https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/2185133/chinas-crowded-labour-market-making-life-tough-foreign-worker

s

s

Comments