The world’s largest pearl: fantastical tale of an 80-year hoax and the men and women who lost millions to its dubious charms.BY MICHAEL LAPOINTE 1 JUN 2018

Supposedly coveted by Ferdinand Marcos and Osama bin Laden, and once valued at US$75 million, a web of fraud, murder and fiction has spread around the ‘Pearl of Lao Tzu’ ever since it was fished from Philippine waters in 1934.

Legend says the diver drowned retrieving the pearl. Trapped in a giant Tridacna clam, his body was brought to the surface by his fellow tribesmen in Palawan, an archipelagic province of the Philippines, in May 1934. When the clam was prised open, the local chief beheld something marvellous: a massive pearl. In its satin-like surface, the chief discerned the face of the Prophet Mohammed, so he named it the Pearl of Allah. At 14 pounds, one ounce (6.38kg), it was the largest pearl ever discovered.

Filipino-American Wilburn Dowell Cobb was visiting the island and offered to buy the pearl. In a 1939 article in Natural History magazine in the United States, he recounted the chief’s refusal to sell: “A pearl with the image of Mohammed, the Prophet of Allah, is earned by devotion, by sacrifice, not bought with money,” he said.

But when the chief’s son fell ill with malaria, Cobb used Atabrine, a modern medicine, to heal him. “You have earned your reward,” the chief proclaimed. “Here, my friend, claim this, your pearl.”

In 1939, Cobb took the pearl to New York, exhibiting it at Ripley’s Believe It or Not on Broadway. Upon seeing the pearl, Cobb said, an elderly Chinese gentleman “of highest culture and significant wealth” named Mr Lee “burst into an hysteria of trembling and weeping”. This was not the Pearl of Allah, he insisted, this was the long-lost Pearl of Lao Tzu.

China’s legacy: the thoughts of Lao Tzu

In about 600BC, the man told Cobb, Lao Tzu, the ancient Chinese founder of Taoism, carved an amulet depicting the “three friends” – Buddha, Confucius and himself – and inserted it into a clam so that a pearl would grow around it. As it developed, the pearl was transferred to ever-larger shells until only the giant Tridacna could hold it. In its sheen, Lee claimed, was not just one face, but three.

On the spot, Lee offered Cobb US$500,000, saying the pearl was actually worth US$3.5 million. Cobb refused to sell and the mysterious Lee returned to China, never to be heard from again. But his spontaneous appraisal – US$3.5 million – still forms the basis of a valuation that has steadily grown, from US$40 million to US$60 million to US$75 million and beyond.

Lee’s recognition of Lao Tzu’s legendary pearl, however, is at the heart of an 80-year-old hoax that has left a trail of wreckage across the US.

Bits of the legend are true: the pearl really was discovered when a diver drowned; Cobb acquired it from the local chief. The rest is a fantasy that Cobb invented.

6th-century BC Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. Picture: AFP

6th-century BC Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. Picture: AFP

In the dry hills of Union City, in the San Francisco Bay area of California, I meet Cobb’s daughter Ruth Cobb Hill. Born in the Philippines, she is now 85 years old and a retired clinical psychologist.

Her father, she says, was born in 1903 on Cuyo, an island in the western Philippines. His father was an American mining engineer, and Cobb grew up affluent, and with a penchant for adventure. As he travelled from island to island, he wrote romantic stories about the people he encountered. “The storytelling part of him was always, always there,” she tells me. “He wanted to be a writer.”

Cobb studied his pearl, sketched it from different angles, and finally saw the turbaned face. He called it the Pearl of Allah in deference to the Palawan chief, who was Muslim, and then – with childlike indifference for the facts – he put words into the chief’s mouth, in the pages of Natural History.

By the time he acquired the pearl, Cobb was a husband and a father to eight children, but domestic life never suited him. When he left for America in 1939, he initially took the pearl to Roy Waldo Miner, a curator at the Museum of Natural History in New York, who wrote a letter certifying it as “a record specimen”. The letter landed Cobb his brief contract with Ripley’s.

The Hong Kong-built junk that was once Ripley’s, believe it or not

Cobb’s American adventure meant abandoning his family to Japanese occupation of the Philippines, which came in 1941. At the age of nine, Ruth witnessed massacres, saw her home razed and lived as a fugitive. Her father joined the Merchant Marines, working in a ship’s kitchen while – in his suitcase – the pearl made an unofficial world tour, travelling all the way to India before the fighting became too heavy to continue.

Upon returning from the war, Cobb settled in San Francisco and life was more austere than he had been used to, though in 1967 he told the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper, “The richest man in the world doesn’t have what I have.”

But what was his pearl really worth? In a way, the pearl was worth only what someone would pay for it. Indeed, also in 1967, Lee Sparrow, who operated the San Francisco Gem Laboratory, helped lend credence to the story of the mysterious Mr Lee. “If Cobb was offered US$3.5 million,” he told the Chronicle, “then that is what it is worth.”

But in Sparrow’s estimation, US$3.5 million would be the bargain of the century. With a whopping 127,574 pearl grains, Sparrow said, the pearl should be valued at US$40 million to US$42 million. That appraisal neatly fitted Cobb’s fantasy, but though he sometimes considered selling the pearl, he never did.

The San Francisco Chronicle article on Wilbur Cobb and his pearl dated April 6, 1967. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

The San Francisco Chronicle article on Wilbur Cobb and his pearl dated April 6, 1967. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

When Cobb died, in 1979, his daughter Ruth was left to settle his estate, and the pearl now proved a tax liability. She consulted a gemmological expert at the US Inland Revenue Service, who arrived at a price of US$200,000. Soon after, a jeweller from Beverly Hills had found a buyer.

And so, 40 years after the Pearl of Lao Tzu had crossed the Pacific, Ruth Cobb Hill – at a Wells Fargo bank in San Francisco, under armed guard – lifted the world’s largest pearl from its safe-deposit box and handed it to one Victor Barbish, who immediately founded a holding company, the World’s Largest Pearl Co Inc, and named himself president.

Then he elaborated on the pearl’s “factual history”.

During China’s Sui dynasty (AD581-618), Barbish said, the pearl’s owner awoke to find a young boy desperate for food and shelter knocking on his front gate, and took him in. One night, the man dreamed that the Pearl of Lao Tzu spoke to him, and prophesied that the boy would initiate a new dynasty, “a reign distinguished by a more humane attitude than has prevailed heretofore”.

The rise and fall of Luoyang, China’s forgotten capital

Sure enough, the boy grew up to become Li Shimin, a founder and second emperor of the Tang dynasty.

Barbish also told of how the pearl ended up in the Philippines, some 2,800km away from the seat of the Chinese empire at Changan (today’s Xian). Still snug in its shell, Barbish said, the pearl found its way onto a trading ship during the Ming dynasty (AD1368-1644) and was swept overboard in a typhoon.

He claimed to have learned these facts from Mr Lee’s family in Pasadena, in 1983. With the help of a former CIA agent named Lewis Maxwell, Barbish said, he planned to sell the pearl to the Lee family.

Yet something always seemed to thwart the pearl’s sale. The problem was not just that Mr Lee never existed, but that Barbish was a magnet for calamity. In Japan, Barbish said, Lee gave Maxwell a cheque for a US$1 million down payment, but after returning home to Alaska, Maxwell died during a botched bypass surgery. The cheque disappeared and Barbish never heard from the Lee family again.

Like Cobb, it seems that Barbish sensed the story of the pearl could be worth more than the object itself.

Ripley’s Believe It or Not New York Odditorium, in 1939. Picture: Ripley’s Believe It or Not

Ripley’s Believe It or Not New York Odditorium, in 1939. Picture: Ripley’s Believe It or Not

When I began looking into the Pearl of Lao Tzu, I heard about Laura Lintner-Horn, a woman who knew more than anyone else about Barbish’s 25-year ownership. I meet Lintner-Horn in Florida and she tells me how she lived with Barbish’s family, on and off, for 50 years – from when she was a little girl until she met her third husband. She has held the Pearl of Lao Tzu in her hands, and thought Barbish was here to fulfil its ancient message of peace. Indeed, she would have done anything for the man she believed to be her father.

“Everybody ends up defending the pearl until they lose,” she says. “And they lose big.”

The tale Lintner-Horn tells, and what I discover during my year-long pursuit of the pearl, braids fact and fiction into a story with everything from contract killings and Chinese emperors to Osama bin Laden.

Con artists strike it rich in Hong Kong with job fraud and identity theft totalling HK$7.82 million this year, or seven times more than all of 2017

For 10 years, Lintner-Horn has been trying to piece together the unusual life of Victor Barbish. Prone to self-invention, he variously said he was a monk, a prize fighter, a CIA agent, business partner of entertainer Sammy Davis Jnr and lover of Sophia Loren. He was poisoned, shot, imprisoned in wartime and possessed by demons. His family calls him a visionary; most others call him a con artist.

Barbish claimed to be the son of infamous gangster Al Capone, and he dressed the part, wearing open jackets, his bare chest heaped with gold chains. Whenever he happened to be near Mount Carmel Cemetery, in Hillside, Illinois, he would place a Cuban cigar on Capone’s gravesite, a tribute to “dad”. In fact, his father was a butcher named Lester Barbish, who married Helen Ruben and had a boy, Lawry Barbish, in New Castle, Pennsylvania.

Victor Barbish and his daughter Gina in 1984. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Victor Barbish and his daughter Gina in 1984. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

The man we know as Victor Barbish makes his debut in public records in 1970, in La Verne, in California’s Los Angeles county. The city council prohibited gambling, but Barbish held bridge sessions at Vic’s Steak House, his restaurant and nightclub.

To put an end to raids by the authorities, he switched from card games to bingo, saying proceeds would go to youth sports in the area. When this failed, Barbish unsuccessfully sued the city, demanding to know “the price of becoming a respectable citizen”.

He then moved to nearby San Bernardino and founded the Church of All Faiths, using religious exemptions to start a bingo operation in a former shop. Now he was Reverend Vic Barbish, who published apocalyptic sermons in the local newspaper while his bingo games took in about US$80,000 a month. The city eventually revoked his gambling licence.

No matter what Barbish tried, he could not shake off a whiff of the illicit; he needed to find something that would legitimise him. He found that something in 1979, when word came to him that the world’s largest pearl was for sale. The price of becoming a respectable citizen: just US$200,000.

In 1985, Barbish moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado, and reinvented himself yet again. As president of the World’s Largest Pearl Co, with his name in The Guinness Book of World Records, he fostered an image of prosperity and ingratiated himself with the city’s jewellers, real-estate agents and car dealers.

Barbish would dazzle those who came into his orbit with gaudy opulence, and then he would ask for an investment, or perhaps a short-term loan – just a few hundred thousand, say – to finesse the passage of a blockbuster deal.

The story-telling part of him was always, always there. He wanted to be a writer

“Victor was constantly saying, ‘I’m working on a US$20 million loan on the pearl, and it’s going to be coming any minute,’” one of his victims tells me. Or he would say he had a buyer – perhaps Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos, or actor Whoopi Goldberg – but deals would fall through, often because Barbish was just too principled.

In the mid-1980s, so one story goes, an excommunicated Iranian princess had brokered a US$40 million sale on behalf of a group in Europe. But when Barbish learned that the buyers were of unscrupulous origin, he called it off.

In 2004, Barbish told news website WorldNetDaily that, back in 1999, he had received a US$60 million offer on behalf of a foreign buyer named Osama bin Laden. According to Barbish, bin Laden had intended to purchase Lao Tzu’s pearl as a gift for Saddam Hussein, “to unite the Arab cultures”. The deal was in place, but bin Laden’s representatives were apparently stopped at the Canadian border.

When WorldNetDaily wrote about the deal, Barbish suggested that it established a link between bin Laden and Hussein – a crucial missing piece of George W. Bush’s justification for invading Iraq. “I just couldn’t sit back and listen to these lies about our government and President Bush,” Barbish told the news site. “Bin Laden tried to purchase my pearl as a gift to Saddam, and Saddam wanted to accept it.”

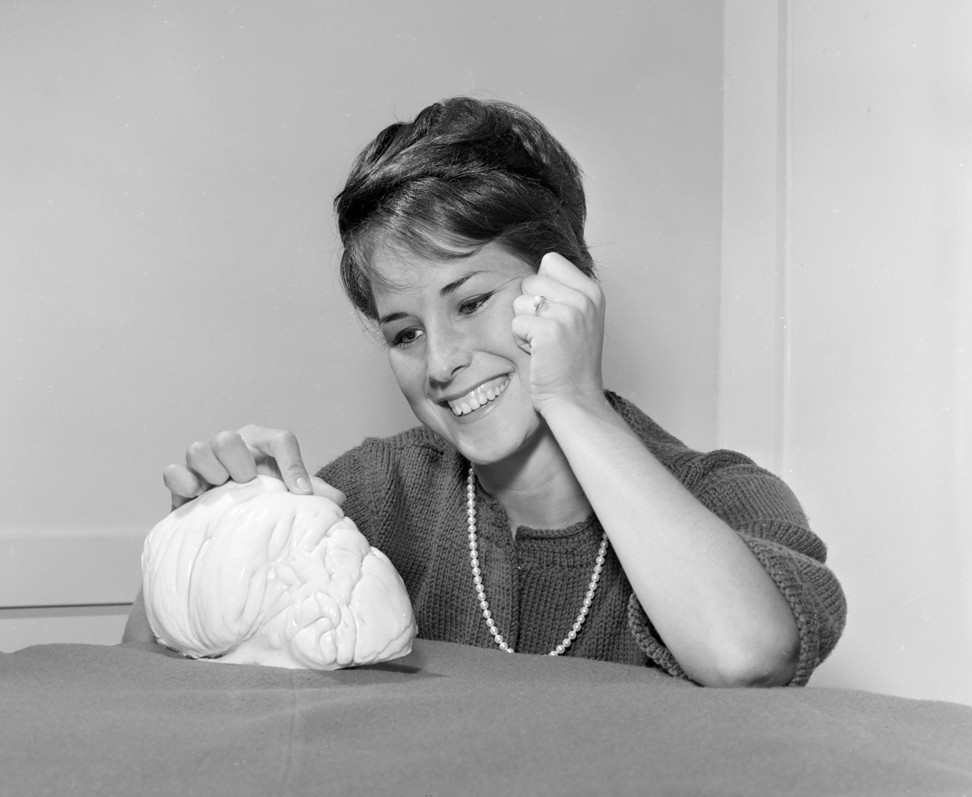

A woman models the Pearl of Lao Tzu in 1964. Picture: Alamy

A woman models the Pearl of Lao Tzu in 1964. Picture: Alamy

Looking back, Barbish’s stories seem so artless, it is hard to imagine how they were believed. After all, his targets were savvy, successful people. But they had one thing in common: a thread of greed that Barbish masterfully teased out.

Some of those he conned fought back, however. Through the 80s and 90s, hardly a month passed without one legal action or another, with characters claiming a share (US$250,000 here, US$500,000 there) of the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

A constant presence in the saga has been Peter Hoffman, the Beverly Hills jeweller who brokered the purchase from Wilburn Cobb’s estate in 1979. When a Colorado judge ordered the pearl to be sold at auction by August 1990 to settle claims, Hoffman went to work. Bidding would start at US$10 million.

Hoffman owns a one-third stake in the pearl and he has always seen himself as its rightful guardian, the only person who could successfully market it. Cobb, he once told a reporter, “saw me in a dream with the three sages, Buddha, Confucius, and Lao Tzu, who said I would be the next caretaker of the pearl”.

For more than 20 years, in fact, the Pearl of Lao Tzu has remained in Colorado Springs. There, the terrible truth is kept a secret: the pearl is not worth what the owners claim. In fact, it is not even a real pearl

In May 1990, Hoffman exhibited the pearl in Los Angeles, the last time it was seen in public. On black velvet and gold lamé, it elicited gasps from reporters, who Hoffman told “the pearl’s purported spiritual powers” were far more important to him than the money, which he pledged to use “to benefit mankind”. As for that money, he expected the pearl to sell for US$25 million to US$50 million. (Citing too much “fake news” about the pearl, Hoffman declined to comment for this article, but noted that it “should be properly referred to as a priceless famous historical artefact”.)

Hoffman has claimed that he was close to a sale several times in the 80s and 90s. Marcos was supposed to buy it, but was deposed, in 1986, before a sale was finalised, and the Sultan of Brunei had been intrigued. The deadline passed, however, and the pearl drifted back into limbo, sealed in a safe-deposit box – right where Victor Barbish wanted it.

For more than 20 years, in fact, the Pearl of Lao Tzu has remained in Colorado Springs. There, the terrible truth is kept a secret: the pearl is not worth what the owners claim. In fact, it is not even a real pearl.

Tridacna clams. Picture: Alamy

Tridacna clams. Picture: Alamy

In the 1939 letter written by Museum of Natural History curator Miner, he calls the item in question a “pearlaceous growth” and stresses that it ought not to be classified as a precious pearl at all. The gems we commonly know as pearls are formed within the organic tissue of saltwater oysters, whose inner shells possess nacre, or mother-of-pearl, which generates a pearl’s signature luminescent sheen. Compared with these gems, Tridacna-clam pearls are more like porcelain. Indeed, the Pearl of Lao Tzu could be likened to a lump of white clay.

Under US trade law, however, it is legal to call such objects pearls; any shelled mollusc – even a snail – can make a pearl. But gemmologists traffic in precious pearls only, and discard the rest as “calcium-carbonate concretions”.

So what was Sparrow’s thinking when he assigned it such a high value in 1967?

I locate a colleague of his, who worked with him for 20 years (Sparrow died in 1990), and she recalls him as being credible, even admirable. But with the Pearl of Lao Tzu, he was pulling a stunt. “I laughed my way through that whole thing,” she tells me, describing how Sparrow was egged on by excited colleagues to inflate the number, until, in a collective frenzy, they reached US$40 million to US$42 million.

In the 1939 letter written by Museum of Natural History curator Miner, he calls the item in question a “pearlaceous growth” and stresses that it ought not to be classified as a precious pearl at all

If the pearl could attract a buyer at that price, then surely Cobb would not refuse to sell (and Sparrow would get a handsome commission). “It’s not like you’re breaking the law,” she adds. “It just makes you look silly.”

The Sparrow appraisal took into consideration the pearl’s “historical significance” as well, claiming it had been “carbon dated to be [plus or minus] 600 years old”. But Michael Krzemnicki, who directs the Swiss Gemmological Institute, tells me there is no record of the pearl ever having been subjected to radiocarbon dating.

Such facts did not inconvenience Barbish. In 1992, he commissioned a fresh appraisal. Michael “Buzz” Steenrod, a former video-equipment salesman now working at the All That Glitters jewellery store in Colorado Springs, prepared the document.

While Sparrow said only that the pearl could be 600 years old, Steenrod’s appraisal emphatically claims, “It has been carbon dated to 600BC.” He estimated its worth at US$52 million. (Steenrod declined to comment for this article.)

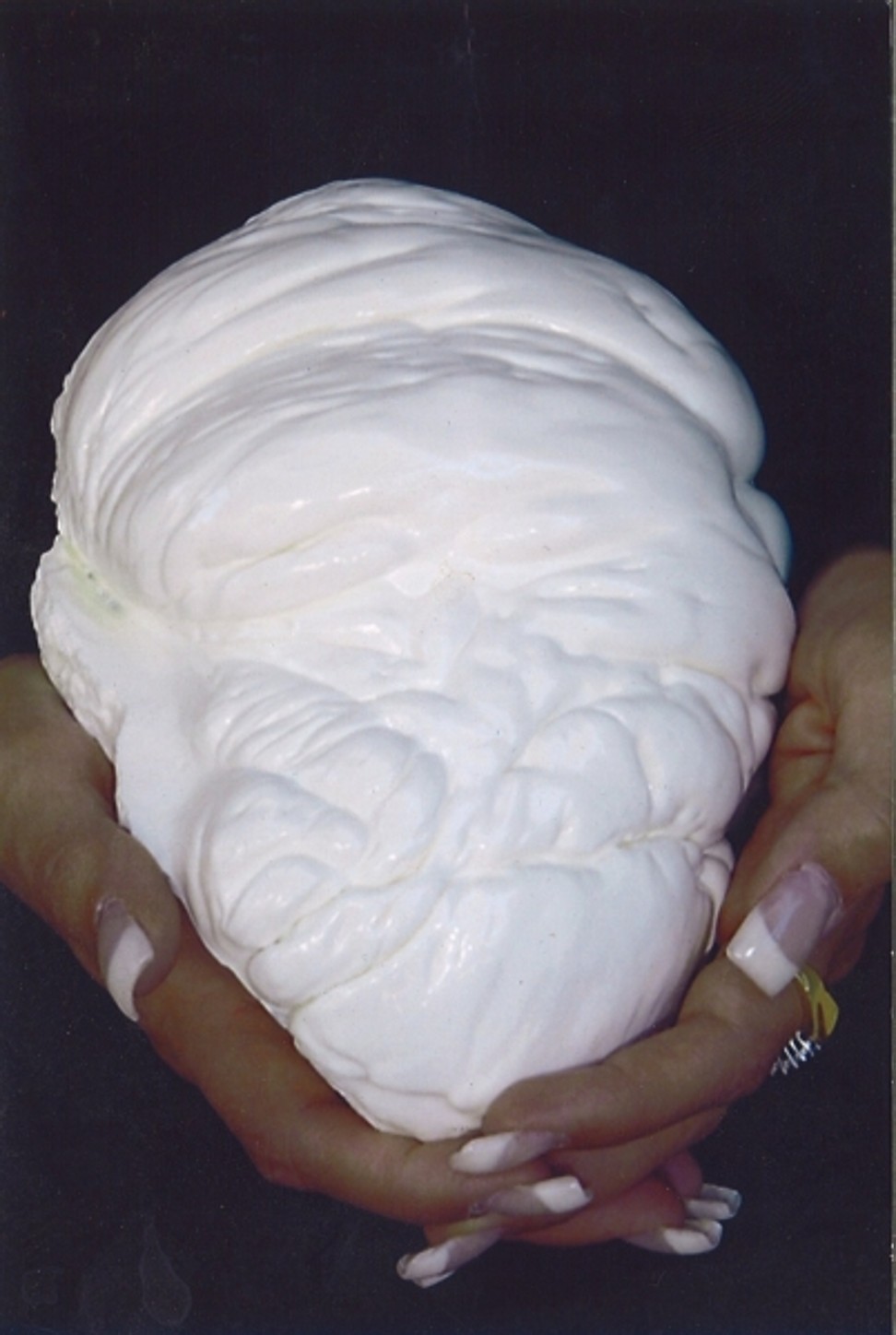

Lintner-Horn holds the pearl. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Lintner-Horn holds the pearl. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Barbish knew that the pearl’s value dwelt in the imagination and relied on weaving a spell around it. The person who became most caught in that spell was Laura Lintner-Horn.

Born in 1953, in Maywood, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, Laura’s parents soon divorced and her grandparents adopted her at the age of three. Being from an Italian Catholic neighbourhood, it was deemed appropriate for Laura’s grandparents to present themselves as her parents while her biological mother and aunt became her older sisters. Laura never doubted these relations, even as her classmates taunted her, “Your mother has grey hair! Your mother’s an old woman!”

Barbish met Laura’s “sister” – actually her aunt – at Paradise Ballroom in Chicago in 1957, and they married. He fabricated gossip that he’d had a one-night stand with Laura’s biological mother and that Laura was his daughter. And so Barbish’s revelation that her parents were really her grandparents only gave way to another primal deception: that he was her father. Until his death, in 2008, she believed it.

“I wanted a normal family so bad,” Lintner-Horn tells me. “I worshipped the Barbishes.” But while Barbish absorbed her into his family, she was always playing catch-up in his affections, and Barbish wielded supreme authority.

When she divorced her first husband, whom she had impulsively married at the age of 18 and who had turned out to be abusive, Barbish told her he had had him killed, and Laura did not learn otherwise until she ran into the man in Colorado Springs some 30 years later. When asked what had really happened, Barbish told her, “Let’s not go there, Laura.”

For decades, Laura had a blind spot for Barbish. Looking back, she is astonished by her gullibility, which she credits to the atmosphere of the Barbish home, describing it as cultlike. “You asked permission for everything,” she says.

Laura Lintner-Horn and the Pearl of Lao Tzu in Victor Barbish’s Colorado Springs home in 2004. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Laura Lintner-Horn and the Pearl of Lao Tzu in Victor Barbish’s Colorado Springs home in 2004. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Lintner-Horn’s major losses began on August 30, 2000, when Lisa, her daughter from her first marriage, was killed when her car was hit by an 18-wheel truck. At the time, Lintner-Horn was married to Phillip Lintner, an Elvis Presley impersonator. He had raised Lisa from infancy and, when she died, Lintner-Horn says, he destroyed himself in his grief. He drank cheap liquor, smoked cigars and stopped singing. Thirty days after being diagnosed with stomach cancer, Phillip died, on Christmas Eve 2001.

Lintner-Horn retired early, and drew closer to Barbish. In addition to her pension, she had money from the sale of a house, as well as life-insurance payouts from her husband’s and daughter’s deaths – hundreds of thousands of dollars. Barbish convinced her that, in her grief, she was not thinking straight and that people would try to take advantage of her. Would it not be prudent to turn everything over to him, to let him invest the money and steward her accounts?

Everybody ends up defending the pearl until they lose. And they lose big

In 2005, Barbish moved one last time, to Sarasota, Florida. In typically grand fashion, he took up residence in a US$1.5 million house, established a jewellery shop and dissolved the World’s Largest Pearl Co. He had “become weary of the unceasing evils” of those who had tried to possess his pearl. “It draws the wrong type of people,” Barbish told the Associated Press. “It was made to do something good.”

And so he created the Pearl for Peace Foundation, a registered non-profit that pledged to support law enforcement. Anyone who paid a membership fee – from US$25 to US$600 – received a golden badge with an image of the pearl at its centre, and a membership card depicting a dove soaring with the pearl in its grasp. President Bush was named member No 1.

Without access to her own money, Lintner-Horn moved to Florida to help care for Barbish in his twilight years. He installed her as the manager of his jewellery store and the nominal director of the foundation. She believed she was doing solid charitable work. Every day, she randomly selected 30 names from the phone book and called for donations. Barbish had prepared the script: the money would be spent on disabled agents, death benefits and bulletproof vests. The goal was to donate US$20 million. Laura estimates that in just two years on the Gulf coast, Barbish took in about US$5.5 million through a variety of cons.

The Pearl for Peace Foundation’s mission statement ended with what can be read as a blessing or a curse: “Let the Legend and the Legacy live on from generation to generation …”

The Pearl of Lao Tzu. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

The Pearl of Lao Tzu. Picture: courtesy of Laura Lintner-Horn

Today, Lintner-Horn lives just outside Sarasota in a bungalow with her third husband, Robert Horn, along with five borzoi dogs, two cockatoos and a foul-mouthed 68-year-old parrot that once belonged to her father.

The couple married in 2007, one year before Barbish’s death. Horn was excited to join a large Italian family, headed by a man who struck him as “the godfather of Florida”, owner of the world-famous Pearl of Lao Tzu.

One day, he heard his father-in-law on the phone, sounding distressed. Barbish had found a buyer in New York, he overheard, but did not have the cash in hand to securely transport the pearl. The deal was in peril. Horn leapt at the opportunity to help. An accountant by training, he still cannot fathom the spell he was under when he wrote Barbish a cheque for US$100,000.

Barbish made Lintner-Horn sleep in the jewellery shop, to protect the merchandise. When he began telling her that jewellery was missing from the safe, and accusing her of negligence, Lintner-Horn thought she was losing her mind. She staked out the shop from a nearby restaurant, and saw Barbish entering the premises after hours. The discovery prompted her to question him about where the foundation’s money had gone, and the exact nature of his deals. Barbish reacted with hostility.

To his dying breath, Victor Barbish had seen himself as the real victim, a “passionate romanticist” who had placed too much trust in imperfect souls

When Barbish died, peacefully at home in January 2008, Lintner-Horn obtained her adoption papers, from when her grandparents had become her guardians, and did not recognise the name of her biological father, Richard Walters. By the time she tracked him down, she found only his ashes in an urn. He had died in 2007.

So now she knew. A 50-year spell was broken and Lintner-Horn began to perceive the full fraudulence of her past.

She told her husband to hire a lawyer to get his money back. (Her own, she realised, was long gone.) The Barbish family took this as a direct attack, and the couple claim that Mario Barbish (Victor’s son and the executor of his estate) threatened to have them killed if Horn pursued his money. Lintner-Horn says it was not the first time she feared for her life; she had earlier hidden a letter reading, “if my husband or I come to harm, please investigate”. (Mario Barbish denies having issued the threat, calling Laura a “delusional woman” and disputing her version of events.)

Yet to his dying breath, Victor Barbish had seen himself as the real victim, a “passionate romanticist” who had placed too much trust in imperfect souls. “I almost was a billionaire,” he lamented in his will, “but due to dishonest law firms, banks and brokers, I got swindled out of my wealth.” Still, he took solace from the fact that his legacy was secure. “Fortunately you, my loved ones, were protected,” he wrote. “You have an article in your corporation that is valued between $38-$60 million.”

Beneath a signature that does not appear to be his own, Barbish added an apt motto for his life: “This is who I am and wish to be.”

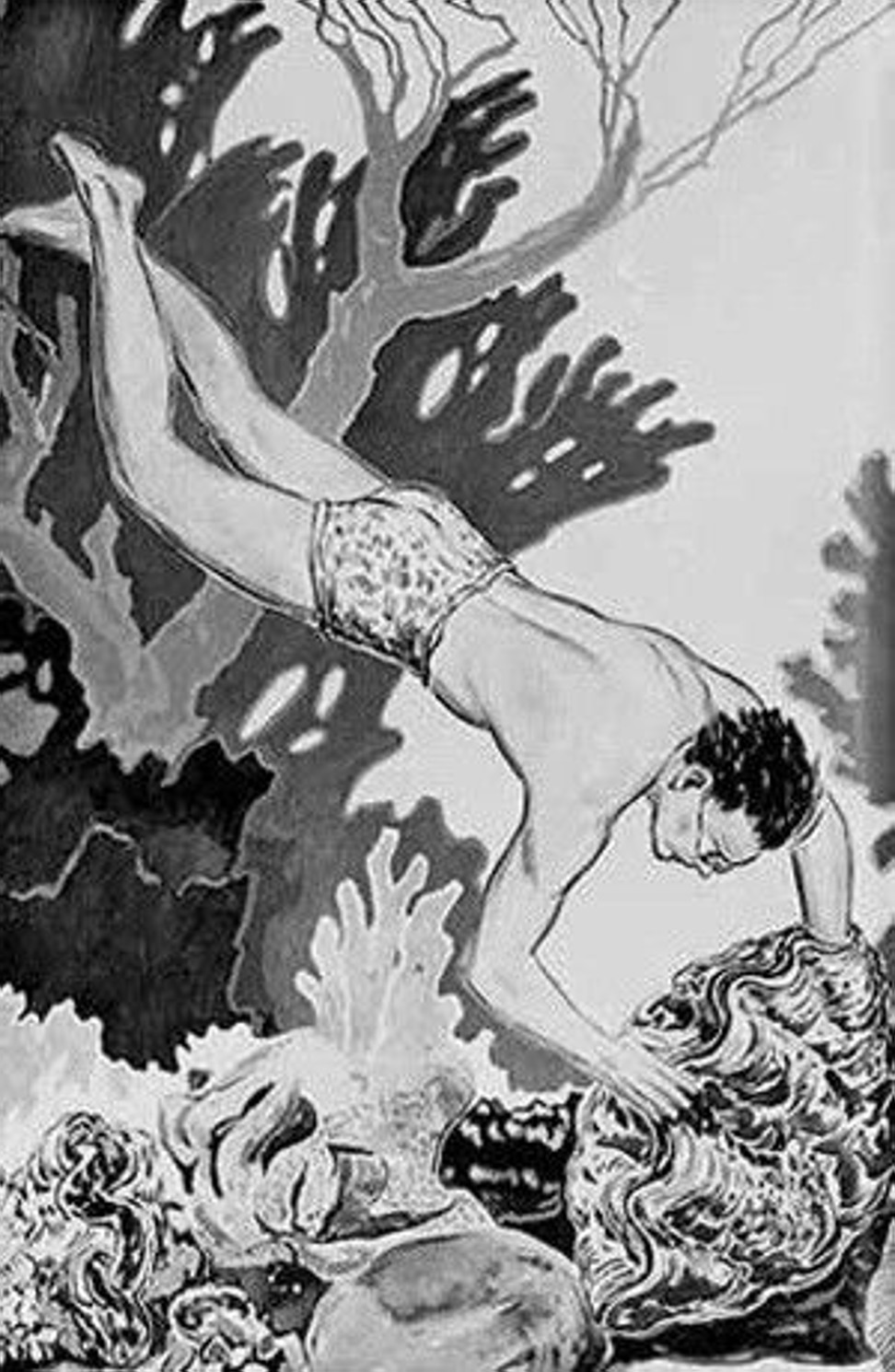

Diver Trapped by a Clam, by Joseph M. Guerry.

Diver Trapped by a Clam, by Joseph M. Guerry.

Lintner-Horn has been deconstructing Victor Barbish’s life in her memoir, The Last Con. When finished, the aim is to self-publish the book and tour it through the cities where Barbish lived, laying waste to the myths he constructed. It is also hoped that The Last Con might be made into a movie, a stage play and an episode of television show American Greed.

Whatever success The Last Con enjoys, it will not make up for Laura’s losses.

Before leaving Florida, I visit the lawyer for the Barbish estate. I see Horn’s name on a list of claims, along with dozens of others. Despite the alleged threats, he had pursued his money after all. But Barbish’s other assets cannot come close to satisfying everyone. Only a sale of his share in the pearl might initiate the needed cascade of cash. Even the estate’s lawyer says he is owed half a million dollars. When I ask why he keeps working the case, he says he has to know how the story ends.

For decades, the pearl case has dragged on in court, as litigants have tried to force a sale and get their money back. The original players are passing away (only Hoffman remains) and old animosities are re-enacted by latecomers, like a famous show revived by understudies.

This state of paralysis was determined by the violent fates of two women, who died without ever hearing of the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

After midnight on March 25, 1974, Ann Phillips was riding in a Cadillac with her husband, Tom, on the Hancock Expressway, in Colorado Springs. When a police light swirled behind them, Tom dutifully pulled over. But instead of police, masked men emerged from the car. They shot Ann dead, knocked her husband unconscious, and fled.

I totally believe in the entire story. I don’t question it at all. It’s like I’m a Christian, I believe in Jesus Christ. Can I prove it? No, it’s a belief

Twenty months later, on the evening of November 23, 1975, a man answered the door at the house of his aunt Eloise Bonicelli on West Arvada Street, also in Colorado Springs. As soon as the nephew opened the door, a stranger shot him in the chest and stormed the house. The nephew escaped to the basement, and later found his aunt on her bedroom floor, dead from a bullet through the heart.

For 25 years, the murders went unsolved. But as it turned out, the husbands of Ann Phillips and Eloise Bonicelli had things in common: they had both hired a hitman to kill their wives, and they both became investors in the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

Joseph Bonicelli owned a bar, a used-car business and a construction company in Colorado Springs, but many former acquaintances recall him as a mobster, or at least a big-dreaming “gangster type”. In the 70s, he built a Nascar-style racetrack, the Colorado Springs International Speedway.

Tom Phillips also owned a bar, but was less entrepreneurial. He was a heavy gambler who had an uncanny knack for getting close to people with money, people like Bonicelli. Even those who loathed Phillips admit that he was charming.

By his own admission, Phillips contracted the murder of his wife to collect on her US$300,000 life insurance. He paid a local barber to arrange the hit, staged to look as if he was the victim of a robbery-homicide. So pleased was Phillips with the barber’s service that he recommended it to Bonicelli, who was facing a costly divorce. Neither man was ever brought to justice – at least not while they lived.

Denied Chinese lawyer Hong Yeng Chang may get justice, 124 years on

In Colorado Springs today, some controversy remains over why Bonicelli was finally accused of arranging Eloise’s murder, several years after his death in 1998. Her children say they were motivated to reopen the case by a desire to honour their mother’s memory; others claim that it was an attempt to wrest control of Bonicelli’s estate from his new wife and her daughter, to whom he had left everything.

The means by which Bonicelli was posthumously tried have certainly invited questions. In exchange for testifying against the dead man, Phillips was granted full immunity for arranging his own wife’s murder. Even though he had been the connection between Bonicelli and the hitman, and committed the same heinous crime, Phillips was allowed to go free. He has since died.

Based on the Phillips testimony, the children of Eloise Bonicelli brought a civil suit against their dead father’s estate, which possessed at least one major asset that they knew of: a one-third stake in the Pearl of Lao Tzu.

It transpires that around 1984, Phillips introduced Bonicelli and Barbish, and Barbish brandished a contract for a sale purportedly authored by Marcos. Bonicelli had just sold his speedway for US$750,000. He sank the whole sum into the pearl.

Naturally, the sale fell through, and Bonicelli never got over it. In his final years, he would sit at his kitchen table with a handgun, promising to kill Phillips on sight. As for Barbish, Bonicelli said he wanted to blow up his house.

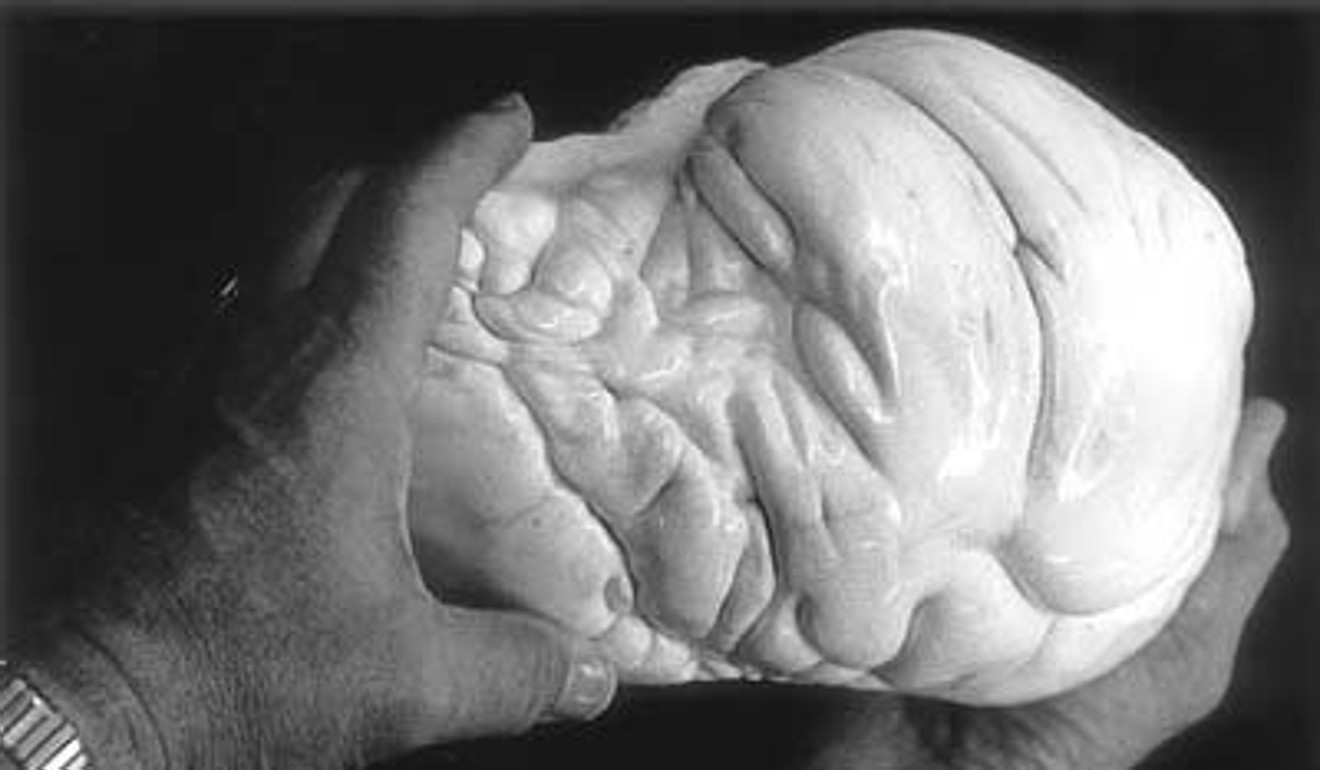

A pearl weighing 34kg found by another fisherman from Palawan, in 2016. Picture: EPA

A pearl weighing 34kg found by another fisherman from Palawan, in 2016. Picture: EPA

In 2005, seven years after his death, Bonicelli was found responsible for his wife’s murder. The judgment was directly tied to the value of the pearl. Though defence lawyers produced records showing that it had only ever sold for US$200,000 (when Barbish bought it from Cobb’s estate), the testimony of Steenrod carried the day. He had spruced up his previous appraisal, adjusting for “economic fluctuations”, and set the pearl’s value at US$59.75 million.

The jury awarded Eloise Bonicelli’s children what was reported to be the largest wrongful-death judgment in Colorado history: US$32.4 million.

Today, the Pearl of Lao Tzu is legally divided between Hoffman and the estate of Barbish; Eloise Bonicelli’s children are owed half of Barbish’s share. The court battles have waylaid efforts to sell the pearl. But toward the end of 2017, I began to hear whispers that the path might be clearing.

Curious to know the status of the pearl, I meet Mario Barbish for lunch on the outskirts of Colorado Springs. “I totally believe in the entire story,” he tells me. “I don’t question it at all.” In short, he believes the pearl was cultivated in ever-larger clams through the centuries; he believes Lao Tzu’s amulet is still lodged deep inside. “It’s like I’m a Christian,” he says. “I believe in Jesus Christ. Can I prove it? No, it’s a belief.”

Mario also believes that the pearl’s reputation has been unfairly sullied. What the jewel needs is positive coverage, positive promotion, maybe a world tour. “It’s really time to blow life back into the pearl,” he says, and to that end, he shows me a brochure he has compiled. It includes photos of the pearl laid out on what appears to be a beach towel, and several pages of text relating the legend.

Only such a campaign might attract the right buyer, Mario insists. As for the price, he produces a copy of the Sparrow appraisal, and cites US$100 million as his benchmark. When I ask whether he would consider selling it through an auction house, he demurs. And little wonder – the big-name houses appear to doubt that the pearl has any real value at all.

The pearl would amaze you if you just held it in your hands. A lot of this garbage you’re spewing out of your mouth, you would let it go, because you’d feel that intrinsic value just holding the pearl

I obtain a memo circulated to the pearl’s owners in August 2016 by David Beck, a lawyer in Santa Cruz, California, who represents the interests of a long-deceased man. (“I started working the Pearl case when I was a new attorney in the mid-1980s,” Beck writes in the memo. “Now I am nearing retirement.”) Slowly but surely, he saw the many claims on the pearl defeated; only Joseph Bonicelli’s has held up in court.

At the time of the memo’s writing, Beck stood as the last lawyer still trying to wrestle money out of the pearl. In the final episode of his 30-year struggle, he filed a motion to compel a sale. He wanted to understand how such a sale might occur, and he had asked the esteemed natural-history department at Bonhams, the British auction house, what a sale might raise.

The department prepared a proposal. But it showed no US$100 million figure, no US$75 million, no US$42 million. Instead, Bonhams offered an estimate of US$100,000 to US$150,000. “The Pearl has no value except for any historical value there may be,” Bonhams said. “Beyond that, it is a mere curiosity.”

Beck’s memo was met with silence.

On February 28, this year, a US district court denied Beck’s motion. And so, after more than 30 years, the final claim on the Pearl of Lao Tzu was vanquished.

But obstacles would have remained regardless. Mario Barbish tells me that Asia would be his ideal market. But because the Tridacna clam is an endangered species, to export the pearl, the Philippines would probably have to endorse the transaction – an unlikely scenario.

A buyer must emerge from within the US, but newspapers in the country have described the pearl as “wrinkled”, a “deformed brain” and “a blob”. “It’s not the sort of thing you wear around your neck,” one lawyer said, “unless you’re the Incredible Hulk.”

Poor Philippine fisherman finds ‘world’s largest’ pearl, hides it under his bed as good-luck charm for a decade

Perhaps its status as the world’s largest pearl would be sufficient enticement, but, in 2016, a Palawan fisherman came forward with a specimen he had discovered 10 years earlier when his anchor snagged a giant clam. While it has not been officially verified, this pearl reportedly weighs 75 pounds (34kg).

A day after Beck’s motion is denied, I call Mario Barbish. He wants to know the status of my story, which he hopes will focus on the pearl’s beauty and religious significance. When I describe what I have learned, his affable tone disappears. “You’ve never seen the pearl,” he says. “You’ve never seen the growth lines. You don’t know anything about the pearl.”

Only Mario has the documents proving the valuation beyond reasonable doubt but, when I ask him to produce them, he refuses. “The pearl would amaze you if you just held it in your hands,” he says. “A lot of this garbage you’re spewing out of your mouth, you would let it go, because you’d feel that intrinsic value just holding the pearl.”

The Pearl of Lao Tzu is not a gem, Mario tells me; it’s a “religious artefact”. And just as if the Shroud of Turin went up for auction, he says, those who believe are the ones who will bid. The appraisals will become credible, as if by magic, once you put your faith in the story. (Not the Bonhams appraisal, however; Mario says, “They’re out of their mind.”)

When I hang up, I think of something Wilburn Cobb’s daughter Ruth told me. We were discussing the new, 75-pound pearl and what its discovery meant. Cobb’s pearl was still the famous one, she said. “But the fame came from the stories, and my father started that. And I don’t know what that brings.”

The pearl’s long, destructive fiction appears to end with its owners now left holding what is likely the world’s second-largest pearl – a bogus religious artefact – seemingly unable to accept the truth. Stare long enough and the owners’ stubborn faith looks like that of Victor Barbish, who stitched myths together and called them history, or like that of Wilburn Cobb, who never relinquished his romance.

They begin to seem like the diver, who drowned all those years ago, when he glimpsed that first fateful flash of white.

The Atlantic

http://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2148579/worlds-largest-pearl-fantastical-tale-80-year

Comments