- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Gestalt Principles

Your constantly-updated definition of Gestalt Principles and collection of topical content and literature

What are Gestalt Principles?

The Gestalt Principles are a set of laws arising from 1920s’ psychology, describing how humans typically see objects by grouping similar elements, recognizing patterns and simplifying complex images. Designers use these to engage users via powerful -yet natural- “tricks” of perspective and best practice design standards.

The Gestalt Principles – a Background

The Gestalt Principles of grouping (“Gestalt” is German for “unified whole”) represent the culmination of the work of early 20th-century German psychologists Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Kohler, who sought to understand how humans typically gain meaningful perceptions from chaotic stimuli around them. Wertheimer and company identified a set of laws addressing this natural compulsion to seek order amid disorder, where the mind “informs” what the eye sees by making sense of a series of elements as an image, or illusion. Early graphic designers soon began applying the Gestalt Principles in advertising, encapsulating company values within iconic logos. In the century since, designers have deployed Gestalt Principles extensively, crafting designs with well-placed elements that catch the eye as larger, whole images so viewers instantly make positive connections with the organizations represented.

The whole is other than the sum of the parts.

- Kurt Koffka

CEO of Syntagm, UX Strategist and author, William Hudson explains the Gestalt Principles’ UX relevance.

Gestalt Principles

Some of the most widely recognized Gestalt Principles include:

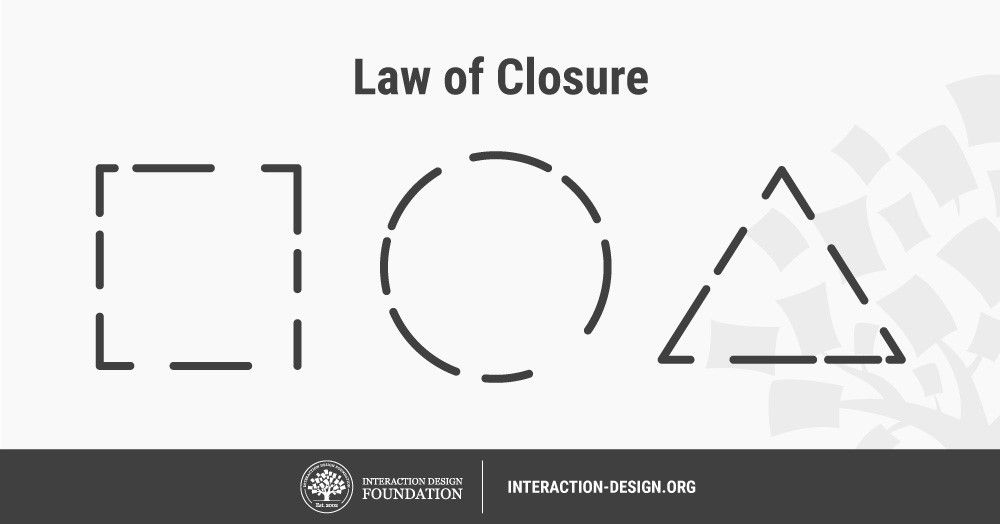

Closure (Reification): Preferring complete shapes, we automatically fill in gaps between elements to perceive a complete image; so, we see the whole first.

Common Fate: We group elements that move in the same direction.

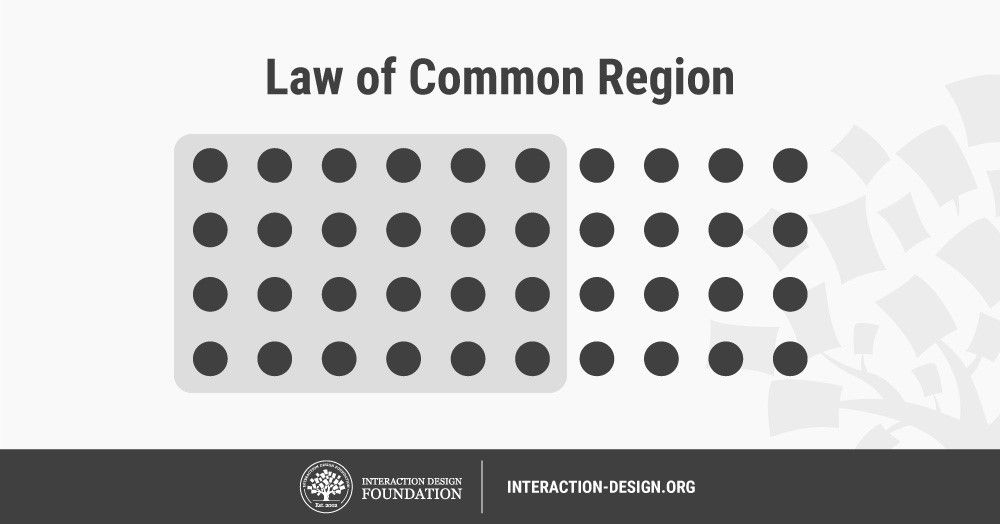

Common Region: We group elements that are in the same closed region.

Continuation: We follow and “flow with” lines.

Convexity: We perceive convex shapes ahead of concave ones.

Element Connectedness: We group elements linked by other elements.

Figure/Ground (Multi-stability): Disliking uncertainty, we look for solid, stable items. Unless an image is truly ambiguous, its foreground catches the eye first.

Good Form: We differentiate elements that are similar in color, form, pattern, etc. from others—even when they overlap—and cluster them together.

Meaningfulness (Familiarity): We group elements if they form a meaningful or personally relevant image.

Prägnanz: We perceive complex or ambiguous images as simple ones.

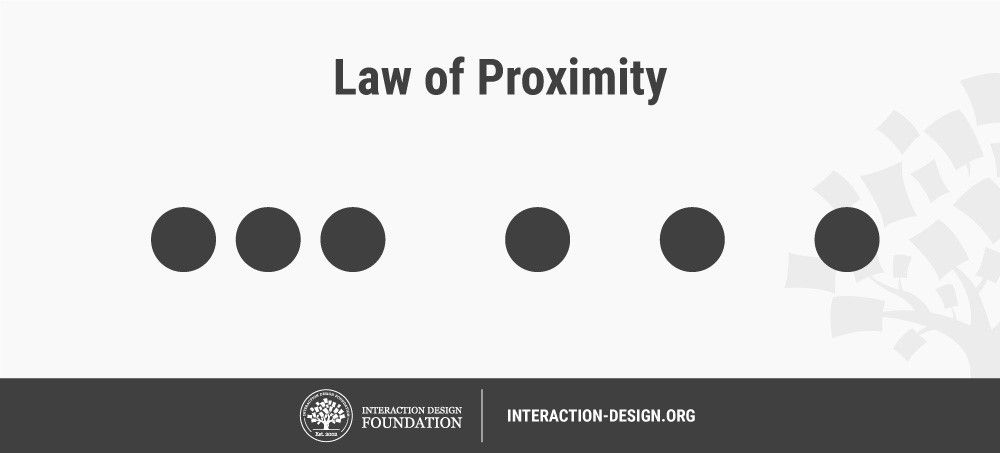

Proximity (Emergence): We group closer-together elements, separating them from those farther apart.

Regularity: Sorting items, we tend to group some into larger shapes, and connect any elements that form a pattern.

Similarity (Invariance): We seek differences and similarities in an image and link similar elements.

Symmetry: We seek balance and order in designs, struggling to do so if they aren’t readily apparent.

Synchrony: We group static visual elements that appear at the same time.

Gestalt Principles are in the Mind, Not the Eye

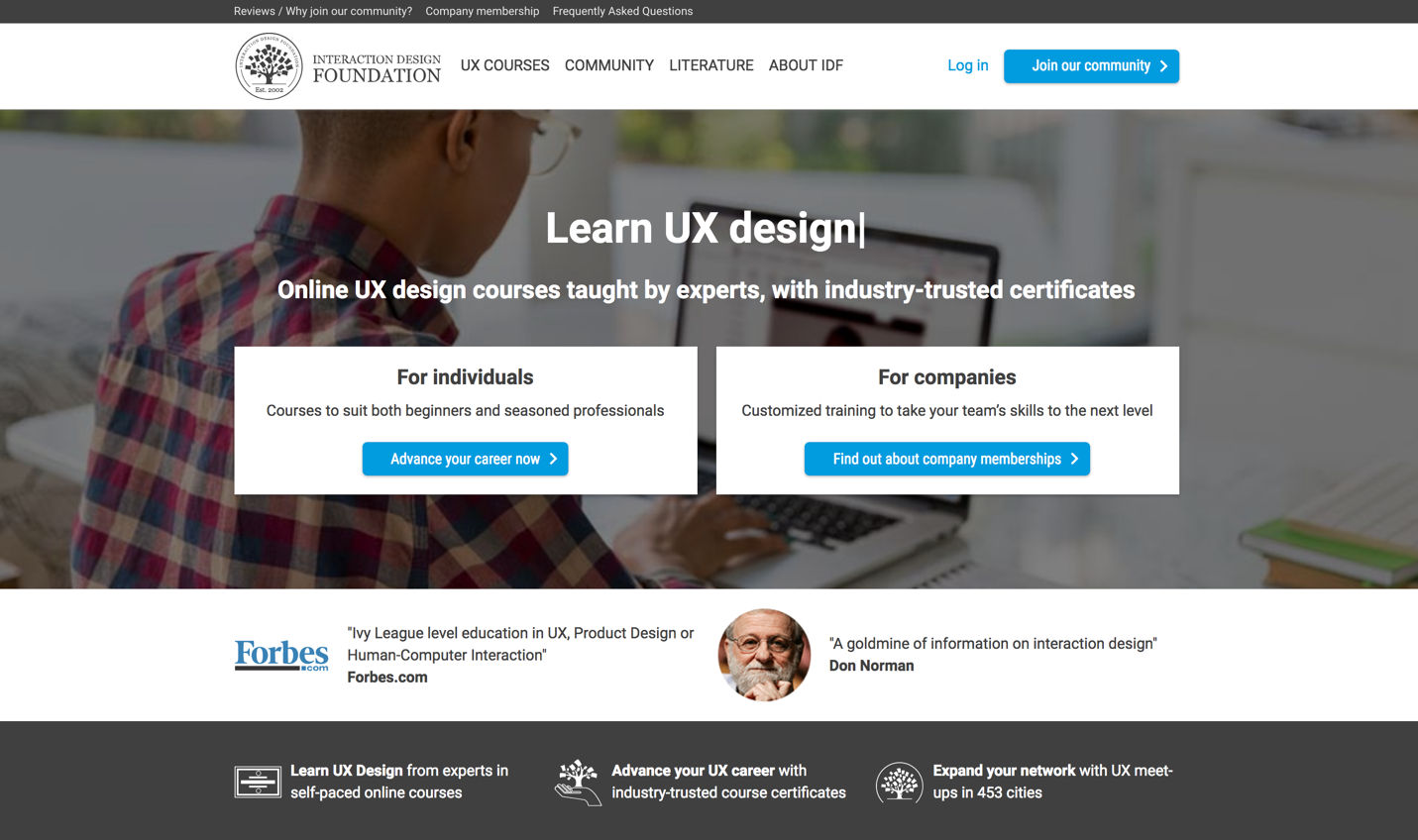

The Gestalt Principles are pivotal in UX design, notably in interfaces, as users must be able to understand what they see—and find what they want—at a glance. A good example are the principles of proximity and common region, as seen in the IDF landing page, below – where colors and graphics divide the page into separate regions. Without it, users will struggle to make associations between unrelated clustered-together items, and leave. For designers, the true trick of Gestalt is never to confuse or delay users, but to guide them to identify their options and identify with organizations/brands rapidly.

Designers must appreciate how the mind strives for ordered pictures and how easily ill-ordered elements frustrate users. Some images are ambiguous; in trying to “decode” Rubin’s Vase, we possess information about profiles and vases, and perceive it in two ways – but never simultaneously. In closure (reification), we recognize a whole image, and deconstructing it into its various elements takes considerable effort. Designers must remember that while the Gestalt Principles are universal to the human experience, fine-tuning their application demands attention to color use and other cultural considerations.

Learn More about the Gestalt Principles

Learn more about how designers employ Gestalt psychology, by enrolling in the IDF’s online course: https://www.interaction-design.org/courses/gestalt-psychology-and-web-design-the-ultimate-guide

For more on building relationships via Gestalt Principles, see Smashing Magazine’s article: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2016/05/improve-your-designs-with-the-principles-of-closure-and-figure-ground-part-2/

Usertesting.com’s blog features many tips and examples: https://www.usertesting.com/blog/2016/02/24/gestalt-principles/

Content strategist Jerry Cao’s piece on Gestalt Principles for Designers offers many helpful insights: http://blog.teamtreehouse.com/gestalt-principles-designers-applying-visual-psychology-modern-day-design

Comments