Indian girls wear masks depicting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and hold up new currency notes in November, 2016. Photo: EPA

Few things can hold back an economy as effectively as a bloated public sector and mismanaged government finances. India has both of these problems. Even the government’s own auditor, the comptroller and auditor general, has pointed out problems in the budget.

Let us start with the oversized public sector. The government runs numerous “businesses” called public-sector undertakings, which operate in industries such as telecommunications, banking, construction and petroleum. Almost all make losses and waste taxpayers’ money. Perhaps the most notorious is

, whose losses run into hundreds of millions of dollars annually and owes more than US$8 billion. More than US$4 billion has been poured into it in the past seven years alone.

Such inefficient firms also create opportunity costs. Air India’s fleet of planes could be better utilised by private airlines. It takes up space and runway time at airports, meaning fewer private flights get to operate. It is the same story with other public-sector undertakings, which take up prime real estate, and employ people who could be in more productive jobs in the private sector.

The government also operates at least 18 banks, which

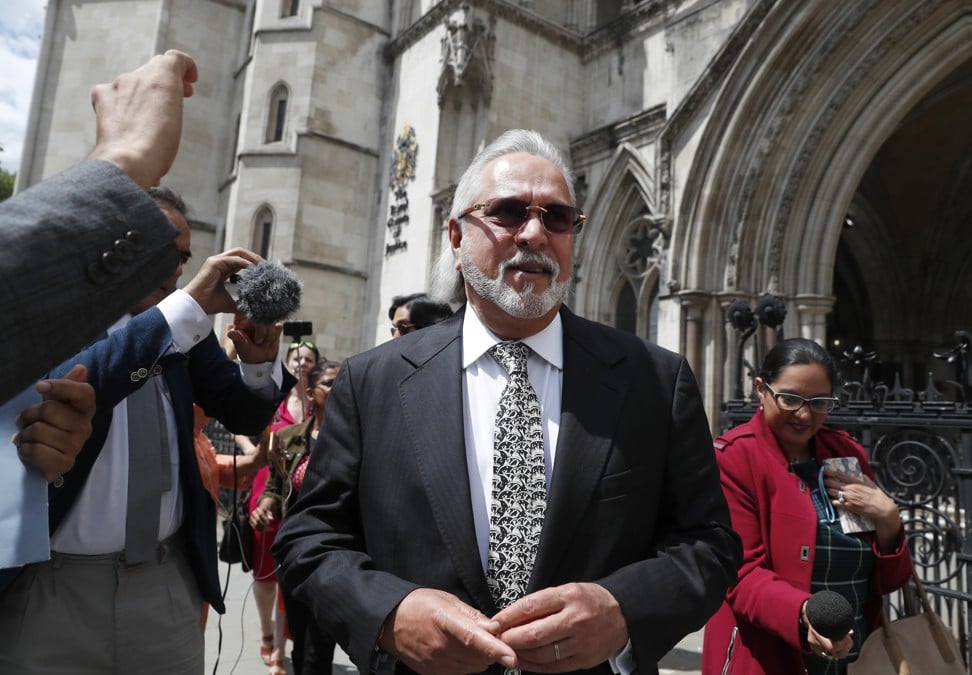

India’s credit market. While private banks assess borrower credibility and business risks, government banks tend to lend based on political considerations. Fugitive businessmen such as

and

obtained multibillion-dollar loans from government banks because of their political connections.

Vijay Mallya outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London last month. He has won the right to challenge in court Britain’s decision to order his extradition to India to face fraud charges. Mallya, whose business empire once included Kingfisher beer, left India 2½ years ago after defaulting on debts of more than US$1 billion linked to a failing venture, Kingfisher Airlines. Photo: AP

These public-sector banks also lend to farmers who have little chance of repaying. Come election time, these loans are

to garner votes. Unsurprisingly, as much as 15-20 per cent of the loans by government banks turn bad. These banks account for around 60 per cent of Indians’ savings, leading to tremendous waste and misallocation of capital.

This looks bad for a government that portrays itself as

and pro-market. So, it has embarked on a programme of “disinvestment”, selling stakes in its public sector undertakings worth US$40.92 billion in the past five years. But what has really happened is that some public-sector undertakings have “acquired” other public-sector undertakings. For instance, Hindustan Petroleum Corporation was “sold” to Oil and Natural Gas Corp, while IDBI, a government bank, was “sold” to Life Insurance Corporation.

After simply shuffling funds around in this manner, the government claims to have raised additional revenue of almost US$41 billion. This is equivalent to me transferring my wallet from the left pocket to the right pocket and saying I am richer. Also note that the “acquisitions” were financed by government banks. So the revenue being presented as an asset is actually a liability for the future.

The appointment of Shaktikanta Das – the civil servant who oversaw Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s demonetisation initiative — as governor of the Reserve Bank of India is seen to have dealt a blow to much-needed reforms for state banks, which make up 70 per cent of the country’s banking system. Photo: Bloomberg

This makes it hard to gauge the government’s true fiscal health. Poor government finances, such as persistent budget deficits or high debt levels, are problematic since they mean higher taxes in the future, which are a drag on economic growth.

Officially, the government has a budget deficit amounting to 3.39 per cent of gross domestic product, slightly better than the target of 3.4 per cent. However, much of the deficit is simply kept off the books. For example, the government-owned Food Corporation of India borrows

from government banks to buy up excess crops from farmers. If this money is included as government spending, the fiscal deficit would have been 4 per cent of GDP.

What is certain ... is that the government cannot be trusted to tell the truth about its finances

Similarly, many subsidies are routed through public sector undertakings and do not show up as spending in official government accounts. If all of that spending were accounted for, the deficit would be much higher.

Officially, government debt is around 70 per cent of GDP. This is too high. We must remember that the borrowing of public-sector undertakings from government banks and the waived loans to farmers must also be included in the debt. After all, money deposited in government banks belongs to Indian citizens and must eventually be repaid to them by the government. Thus, the real outstanding debt is much higher.

It is hard to calculate the exact levels of government debt and budget deficits. What is certain, however, is that the government cannot be trusted to tell the truth about its finances. Its creative accounting might be legal, but it remains fraudulent nonetheless.

Jairaj Devadiga is an economist. His work mainly deals with public policy and economic history. Twitter: @JairajDevadiga

Comments