Hindus from Sindh who fled India for Hong Kong at Partition recall how they built a community

- When India was partitioned in August 1947, 12 million people were displaced, more than a million died and Hindus and Sikhs fled newly created Pakistan

- Some Sindhi Hindus ended up in Hong Kong, where they made a new life but never forgot their cultural heritage

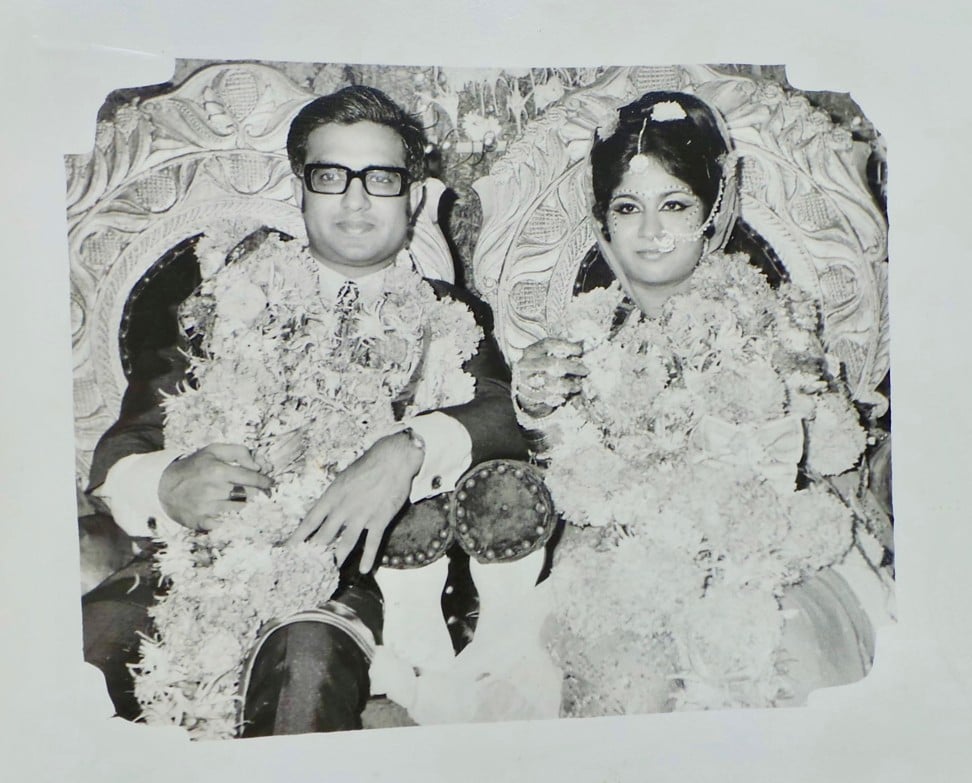

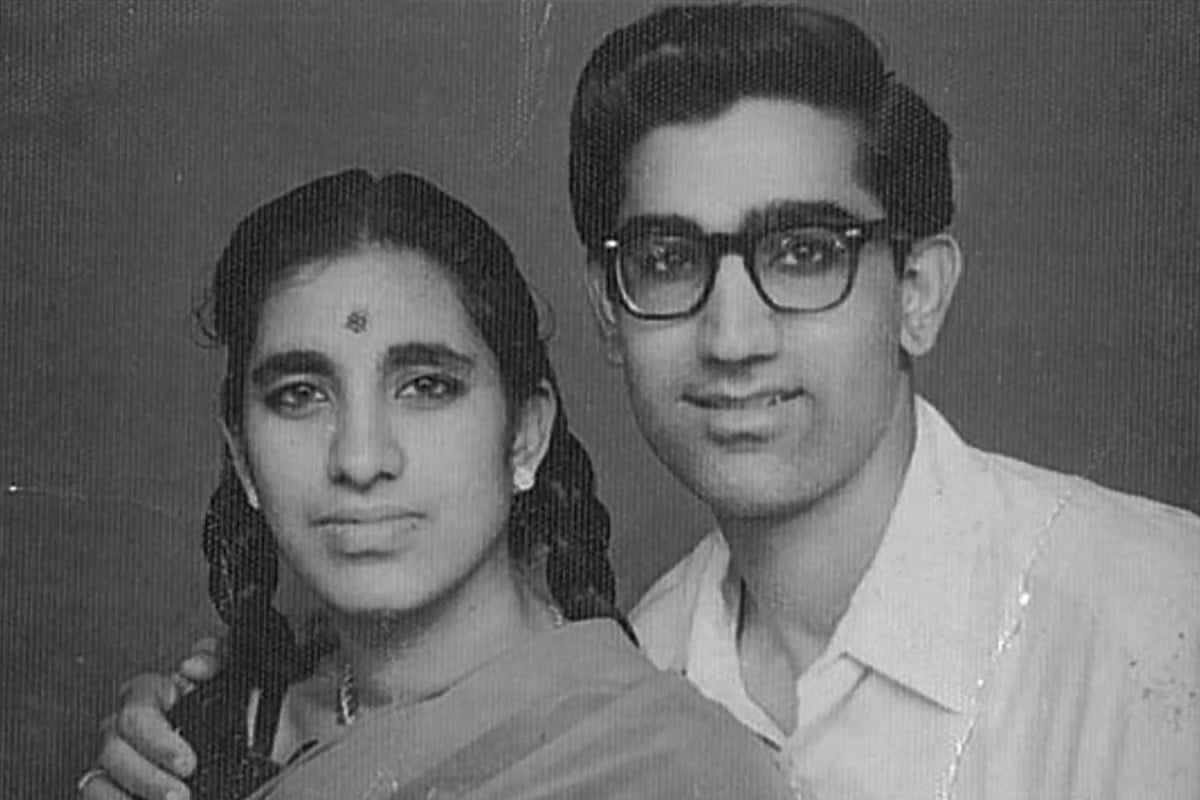

Sindhi Hindu Hotchand Wadhwani with his wife Padma in 1959. The Partition of India led to religious violence and the displacement of millions of Hindus from the newly created Pakistan. Some ended up in Hong Kong.

The Partition of India, following the country’s independence on August 15, 1947, displaced more than 12 million people along religious lines, causing refugee crises and violent tensions that simmer to this day. It resulted in division between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and the largest mass migration in history at a cost of more than a million lives.

Unlike Punjab and Bengal, which were split in two, Sindh province was given intact to the newly created nation of Pakistan. So Sindhi Hindu and Sikh refugees had no non-secular state to call their own. Uprooted from their homeland and culture, their communities were forever displaced.

Seventy-two years later, memories of the horrors and unbearable struggles that unfolded remain raw in the minds of Sindhi Hindus, including those who have since relocated to Hong Kong, which was a British colony until July 1997.

Charlie Daswani was 14 and living in the Sindhi city of Hyderabad when the new borders were drawn. At first his Muslim neighbours remained brotherly, but when an influx of Muslims arrived from India’s Bihar state, Hindu homes were looted and taken, locals were stirred up to join in the violence, and Daswani’s family had to leave with whatever they could carry.

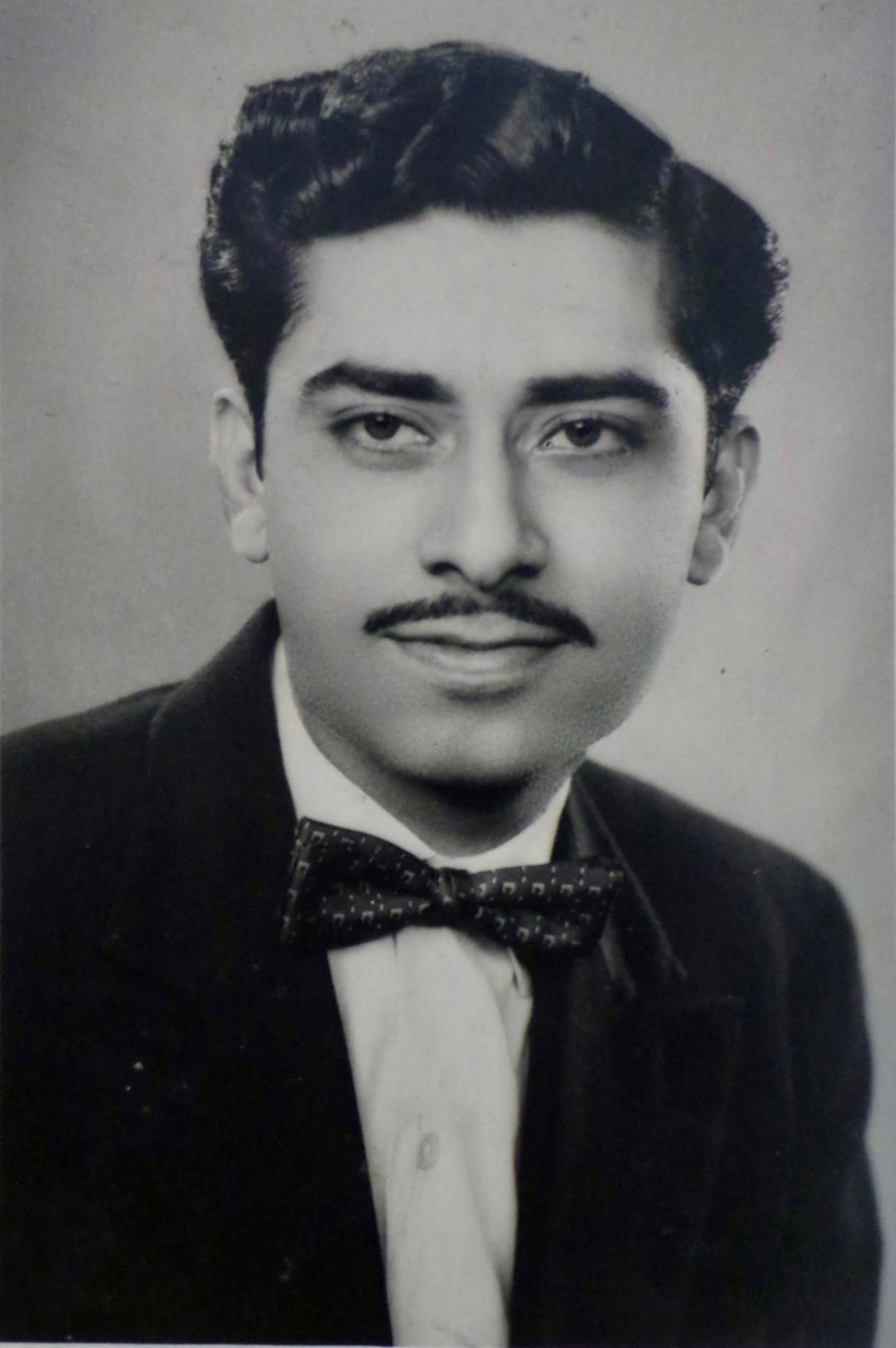

Charlie Daswani was 14 when India was partitioned.

“I had three sisters and we’d heard of horrifying rapes, so we left by train with my aunt’s family and their dog. So-called customs officers stole what they wanted from our cases, but just before leaving a relative of my aunt’s appeared, giving us a bag of gold guineas,” he says.

Daswani was filled with terror when his family were stopped at the border by a group of Muslims who attempted to attack their compartment and take their gold, but luckily the barking of their dog scared them off.

Daswani in 1956 before his performance on India’s Republic Day.

“When we arrived in Bombay, 30 of us slept on the floor of a two-bedroom bungalow, with large rats and ants that fed on our flesh. The nights were terrible, but at least we were alive,” he says.

Daswani came to Hong Kong as a women’s garments salesman in 1955, earning HK$180 a month. After three years he was promoted to manager, but broke his contract to become director of another company as a 25 per cent shareholder.

“I had a wife and three children, so I worked like a dog to make money. My wife Veena’s dream was for me to own my company and in 1985, after 34 years, I opened Charlies International at the age of 53. Sadly, she passed away one year later,” he says.

Daswani’s passion for singing is the one constant that has helped him survive life’s trials. For 20 years he has organised weekly “sangeet therapy” sessions in his home with hired musicians, inviting members of the community to celebrate their memories through song.

Daswani sings the national anthem on Independence Day in 1961.

“We laugh and cry as we sing in the language of our people – a language our grandchildren do not know. We sing about values and traditions that continue to dilute with each generation. Some Hindi songs, like Dil Jalta Hai, stay with you: ‘Your heart is burning, let it burn, but don’t show your tears. Don’t complain.’ It is music to the soul of Sindhi survivors because we know the pain of deep loss but can still laugh at the days to come.”

Hotchand “Harry” Wadhwani was 14 and living in Karachi when his father’s shop was looted by a group of newly arrived Muslims and everything they owned was damaged or stolen.

“Our kind Muslim neighbours hid my father and brother, saving their lives, though we were left penniless. Then the Indian government gave us tickets to leave by boat for Bombay,” he says.

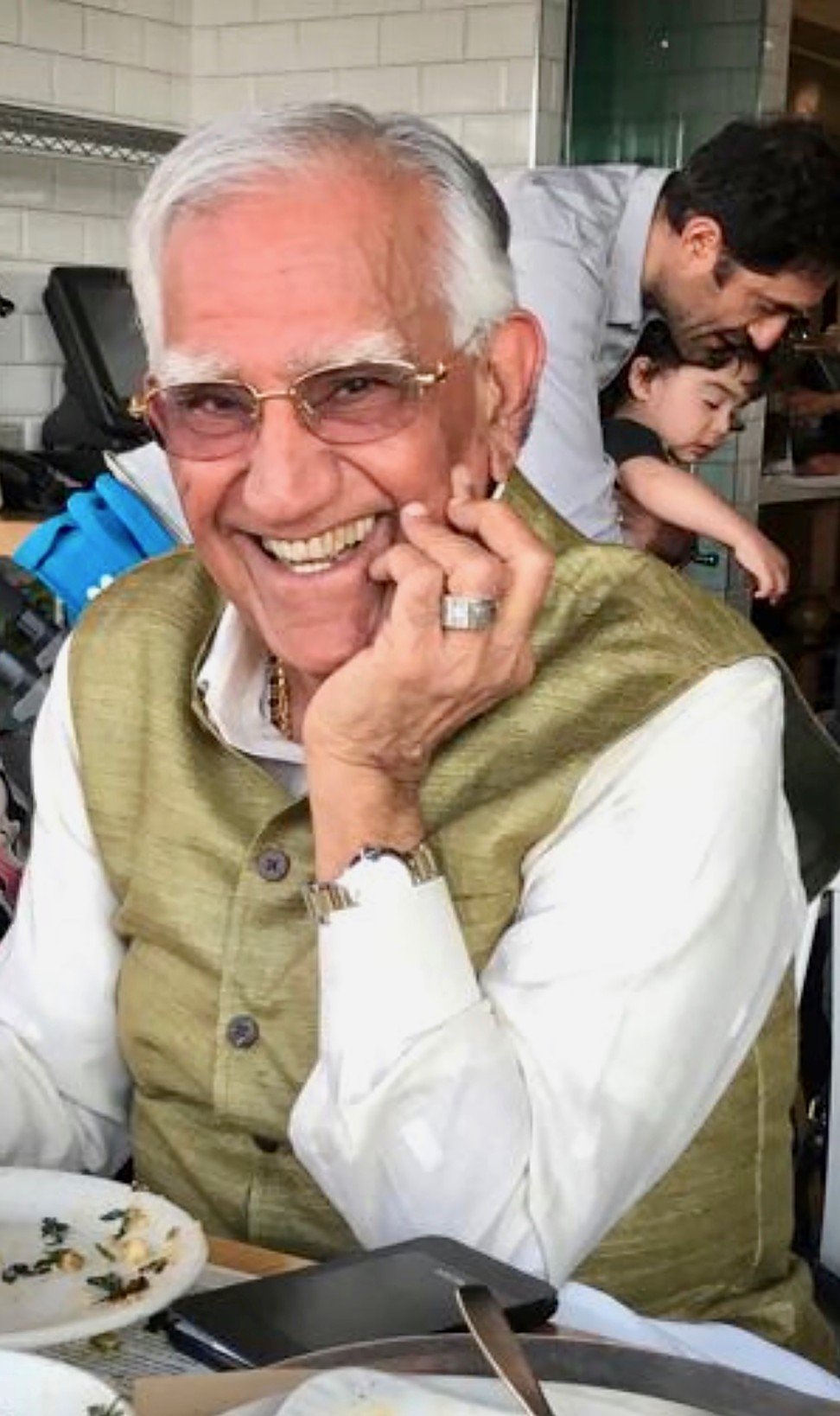

Wadhwani remembers hard times after his family left Sindh province for Bombay.

Wadhwani remembers the intense heat in which his father and brother would carry their textiles merchandise on their backs before laying it out in open market stalls to sell in different villages, day after day.

“I struggled to sit with them for even half an hour, but they worked all day under the blistering sun. My heart broke to see how they sacrificed to put food on the table for us.”

In 1950, the family moved to a cramped and unsanitary refugee camp in Kalyan, a city neighbouring Bombay – or Mumbai, as it is known today. Wadhwani was determined to improve his situation so in 1952, after 20 days at sea, he arrived in Hong Kong to work as a menswear salesman. After stints in Japan, and then for his cousin in Laos, he was given a surprise.

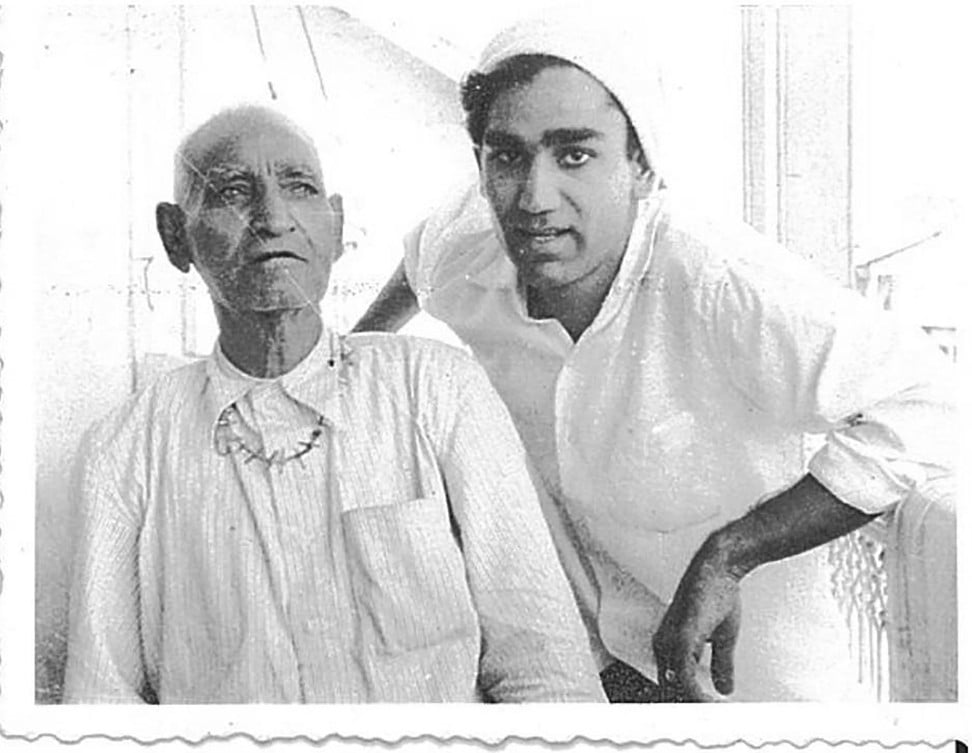

Wadhwani with his father, Manghanmal Wadhwani in 1959.

“My cousin offered me the ‘bonus of a lifetime’ – his wife’s sister. I met my beautiful Padma in January 1959, and a month later we were married. Of course, my mother had a line-up of girls for me to meet, so I wore an ugly pair of short pyjamas when they visited, and they all rejected me.”

Later that year, Wadhwani’s cousin and new brother-in-law decided to sell their company. Wadhwani was quick to buy it, and it continues to thrive. The secret to his success? Giving, he says.

“I believe that when you give – your money, time, love – you get back a thousandfold. In a temple, I was once asked for 20 rupees and told I would get 20 lakhs (two million rupees) in return. So many times, we worry about where the money will go. I just gave and till today I’m still receiving.”

Wadhwani with his family at his grandson Dino’s recent wedding to Anjalisai in Bali.

Wadhwani believes Sindhi culture cannot be “taught” but is “caught” by example.

“At home I spoke in English, Padma spoke in Sindhi, and the children spoke Cantonese in school, but we always ate together, and to me that’s key.”

Notan Tolani was only a year old in 1947 and also living in the port city of Karachi. Six months later, his father died, leaving his brothers to provide for him.

Notan Tolani with his children and grandchildren.

“I was creative by nature, passionate about writing and poetry, but when I visited my nani [maternal grandmother] in the Kalyan camp, I knew that the future I desired would only come from making money in business,” he says.

In 1968, a relative took Tolani first to Manila and then Hong Kong, where he worked as a watch salesman. He managed to save money and, in 1977, opened his own watch manufacturing company, Solar Time.

“Sindhis have something called shidat – a strong force, which made all of us determined to assimilate and survive – so we learned new languages and respected local customs, but in the process failed to pass down our own,” he says.

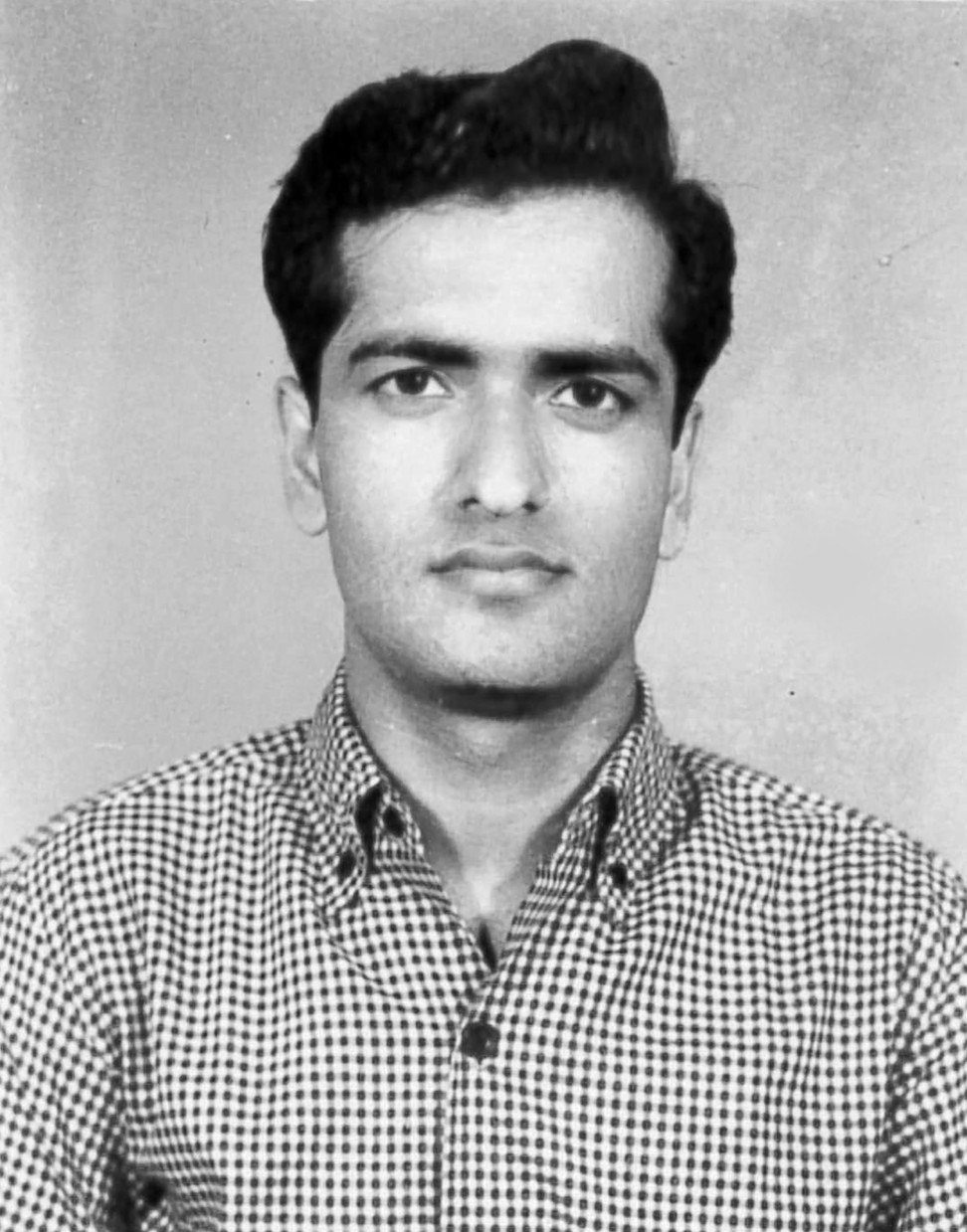

Tolani aged 22 in 1968.

So in 1986, Tolani established Indian cultural programmes, bringing Sindhi singers, films and theatre to Hong Kong. Serving on several Indian associations and as co-founder of the city’s Sindhi Association, Tolani continues to promote the culture of his community.

“Today Sindhis are striving to protect our identity. Thousands celebrate Cheti Chand, our Sindhi New Year, and dedicate events to Jhulelal, our revered Hindu god. It’s true that our youth cannot speak our language, but I believe that to be a true-hearted Sindhi one only needs a love and respect for our values, culture and roots.”

Lal Hardasani was only seven months old at the time of Partition but remembers growing up in Bombay, where his father worked long hours in a silver shop to support the family, including Hardasani’s four sisters.

Lal Hardasani’s father Dipchand Chuharmal Hardasani wearing traditional Sindhi pyjamas, shirt and jacket in 1937.

“Life was hard with the housing shortage. We stayed in a chawl [tenement block], with 10 people sleeping in a small room. I wanted to be a doctor and was smart enough,” he says. However, his college taught classes in English – a language he wasn’t highly proficient in – so he missed his dream.

Hardasani then hoped to train as a businessman in Hong Kong under established Sindhis he had approached, but when they discovered that his father worked for the renowned Vishindas Gianchand silver store, he was given tea and biscuits, then told he would be called when his Hong Kong visa was ready. The call never came.

“Only years later I understood why. Knowing that my father was established, they feared I would learn their trade, open my own shop across the road and become their competitor,” he says.

Lal and Madhu Hardasani on their wedding day in 1970.

Hardasani eventually made it to Hong Kong in 1969, and in 1972 set up his first company, Ashoka Enterprises.

In 1993, Hardasani co-founded the Sindhi Association of Hong Kong, with the aim of promoting and preserving Sindhi language and culture, and passing down its heritage to the younger generation.

“After Partition, we were scrambling to make money and provide for our children. Perhaps, if we’d had a leader to unite us, we would have kept our language and culture alive, but it’s never too late. Our homeland might be gone, but to me, where there are Sindhis, there is Sindh.”

Comments